Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

10 April, 2022

Let’s start with the positive side of this: Musikalische Komödie has put forgotten composer Jean Gilbert (1879-1942) back on stage and presents one of Germany’s once foremost writers of popular musical theater pre-WW1 afresh. That cannot be lauded enough and opens a window to rediscovering a “new” era, after Barrie Kosky has put shows from the Weimar Republic back on the map.

The chorus in “Kinokönigin” at Musikalische Komödie Lepzig, 2022. (Photo: Tom Schulze)

The shows that were created before 1918 – under Emperor Wilhelm II – were heavily censored, so the political and sexual freedom we find in later operettas is only “indicated” here, but still clearly visible if you care to look. And in a way these earlier pieces are just as “modern” as anything Abraham, Spoliansky, Weill or Granichstaedten wrote a decade later.

Die Kinokönigin is one of the first movieland musicals, it premiered in 1913 at Berlin’s Metropoltheater and dealt with a new phenomenon: cinema, as a serious competition to live-theatre, but also as a provocation to the established moral order. (Because early movies – just like operetta and vaudeville – presented sexually risqué stories that some saw as endangering society, it’s the old lament known from Offenbach’s days onwards.)

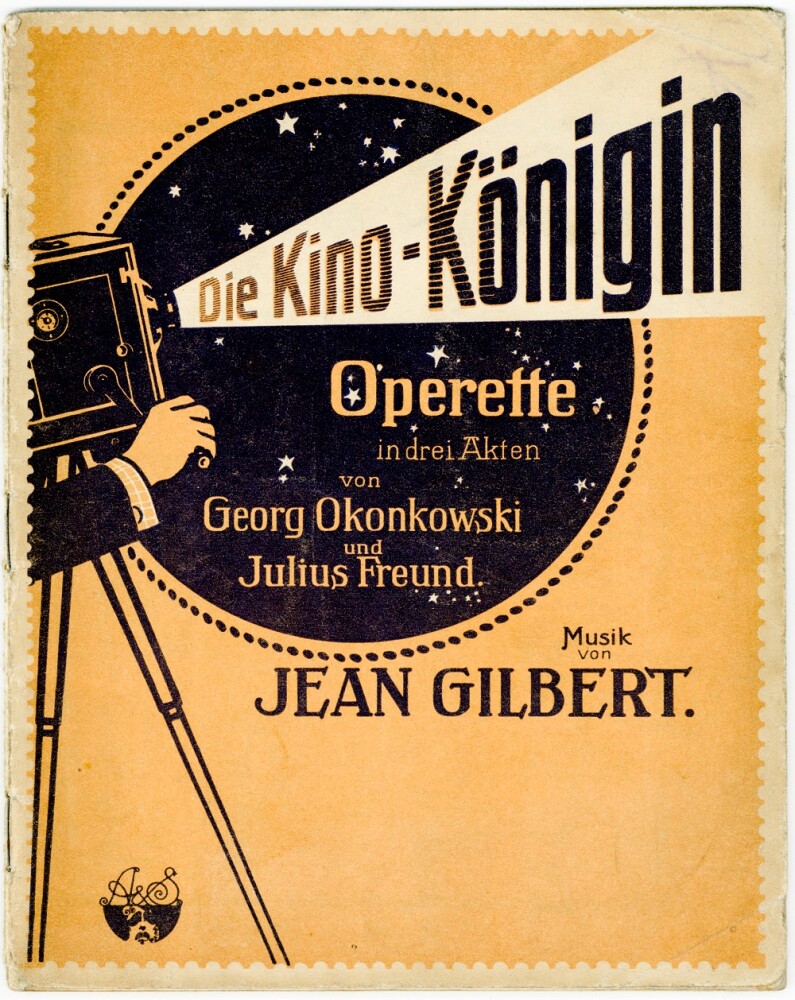

The textbook for “Die Kinokönigin”. (Photo: From Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra”, 2022)

Kinokönigin has a movie goddess as its heroine – 20 years before Nico Dostal did the same thing with Clivia. The story was originally set in the United States and thus had a veritable Hollywood star as the leading character, named Delia Gill. She, and the entire industry she represents, is battled by millionaire Josias Clutterbuck, President of the Temperance League, Vice-President of the Crusade Against Trashy Books, and an anti-cinema advocate! (For more information on the show and the plot, click here for Kurt Gänzl’s essay.)

In the course of the operetta, Delia manages to lure Clutterbuck into her boudoir and seduce the married man while filming it all. This compromising film clip is then shown – as a special attraction in the operetta and as a real on-stage novelty – in the finale, unmasking the double standards of the Temperance League president.

Milko Milev (l.) as Rüdiger von Perlitz with Mathias Schlung as police officer Emil in “Die Kinokönigin” at Musikalische Komödie Leipzig, 2022. (Photo: Tom Schulze)

In the 1960s, Jean Gilbert’s son Robert (of Weiße Rössl, Kongress tanzt and My Fair Lady fame) adapted Kinokönigin for post-war tastes. And he created a new version that proved especially popular in socialist East-Germany, where it premiered at the new Metropoltheater in East-Berlin in the 1963/64 season (the old Metropoltheater had become the Komische Oper by then).

In that new version the story is moved to Wilhelmine Berlin. Delia is not only a German film star but a free-spirited woman fighting for women’s right to vote and for more political participation. Clutterbuck is changed to the reactionary Minister of Culture, renamed Rüdiger von Perlitz. His future son-in-law is turned into a political activist who writes anonymous pamphlets against the government and the emperor; and only after von Perlitz is unmasked as the phony he really is does he step down, paving the way for a new generation, i.e. those who will lead Germany into the first democracy in 1919.

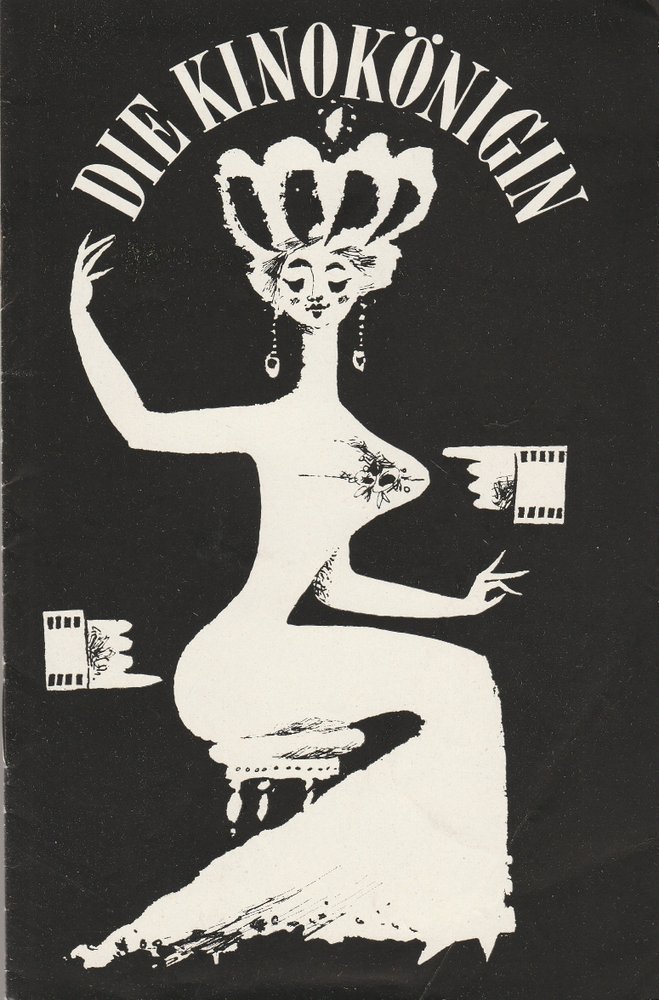

The program book for “Die Kinokönigin” at Metropoltheater Berlin, 1963/64.

It’s not surprising that the DDR found this story very attractive. After the Musikalische Komödie had devoted new attention to shows from the DDR – with the recent revival of Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten and earlier productions of In Frisco ist der Teufel los as well as Mein Freund Bunbury – it’s understandable that they would opt for the 1960s version of Kinokönigin.

However, stage director Andreas Gergen (who made a name for himself as a musicals “expert” with Urinetown/Pinkelstadt and later Der Schuh des Manitu and Ich war noch niemals in New York) is clearly not interested in anything political here. Even though he states in the program booklet that Kinokönigin is “atypical” and an “emancipation operetta”, dealing with “women’s rights, cultural politics, the resistance of avatgarde artists and the conflict between tradition and upheaval”.

Stage director Andreas Gergen. (Photo: Ralf Rühmeier / Wiki Commons)

He labels Kinokönigin “realistic and contemporary” and “very political”. While all of that is certainly true, none of it can be seen on stage. Because Mr. Gergen, together with set designer Stephan Prattes and costume designer Aleksandra Kica, creates a world that cannot be historically located: at times it looks like pre-WW1 via film clips and photographs of “old Berlin” that are shown, some of the costumes suggest the Wilhelmine era, too. But then the dancers woosh in and you wonder if this is all phantasy land lost in limbo. Especially when the dancers undress and stand centre stage in black lingerie, doing a Bob Fosse type of number (with “jazz hands”!) to an orchestral rearrangement that sounds like Mantovani. While that might be seen as an interesting clash of cultures – it isn’t. (Choreography: Mirko Mahr.)

Adam Sanchez and the ladies of the ballet in “Chicago” outfits in “Kinokönigin” at Musikalische Komödie Leipzig, 2022. (Photo: Tom Schulze)

The main problem is that this piece – with its over-the-top characters as political metaphors and with a dazzling film star at the centre – needs a different type of cast, also to do justice to the snappy “Schlager” music which consists of one rousing number after the other, very much pre-shadowing Paul Abraham and his revue style. Grand singing with grand opera voices is nowhere asked for.

Lilli Wünscher as Delia Gill looks ravishing, but she lacks the aura that (let’s say) Christoph Marti brought to his Hollywood star Clivia at Komische Oper Berlin. And Wünscher sings with a fruity soprano in the higher regions of the score, instead of making this an in-your-face feminist declaration of war, for which you need a different style (and voice).

Lilli Wünscher as Delia in “Die Kinokönigin” at Musikalische Komödie Lepzig, 2022. (Photo: Tom Schulze)

The role was originally sung by Ida Russka in 1913 (Kalman’s cheeky Hollandweibchen in 1920), in Vienna Mizzi Freihardt sang Delia. It probably would have been ideal to have someone like Devi-Anada Dahm for that part, but she’s busy around the corner at Staatsoperette Dresden singing Spoliansky’s Zwei Krawatten. (Even if that was cancelled, on the same night that Kinokönigin premiered, due to a positive Corona test.)

While Milko Milev as Rüdiger von Perlitz was an imposing stage figure, he was too nice and harmless to be credible as the reactionary Minister of Culture. His role is supposed to be a caricature (originally the famous Metropoltheater comedian Guido Thielscher played Clutterbuck, stage partner of Fritzi Massary). You need an actor for this part, who has a dangerous edge to him.

Nora Lentner and Vikrant Subramanian in “Kinokönigin” at Musikalische Komödie Leipzig, 2022. (Photo: Tom Schulze)

It’s pointless going through the rest of the cast. Vikrant Subraminian as the political activist Edelhardt von Edelhorst (a new name invented by Robert Gilbert) is as unpolitical as it gets, his naive fiancée Annie (daughter of the von Perlitz family) is anything but naïve. And only Adam Sanchez as the actor Viktor Mathusius cuts a dashing figure, but he, too, doesn’t get a chance to make much of his night spent in an elevator with Auguste, because they both get stuck due to a power failure. Which leads to some amusing complications “the morning after”, only here, they are not so very amusing. Neither is turning film director Eichwald (Andreas Rainer) into a gay man who ends up snogging his blond-and-cute camera man (Alexander Range).

The tragic thing is that newspapers such as Leipziger Volkszeitung now claim that Kinokönigin “was probably rightfully forgotten”. So, any new interest in Jean Gilbert is killed again immediately, just as this revival should have stirred new interest.

Scene from the 1913 Berlin production “Die Kinokönigin”. (Photo: From Evelin Förster’s book “Die Perlen der Cleopatra”, 2022)

Is there anyone to blame? Most certainly Andreas Gergen, who doesn’t seem to know what to do with the piece and just has gym-fit dancers running around doing “business as usual” (which after Otto Pichler’s operetta choreographies really looks lame). Also, it’s very puzzling why Musikalische Komödie didn’t bother to reconstruct the lost 1913 orchestral score/version. And if they opt for the DDR version: why not play that with all of its political and ideological relevance?

The first night audience applauded enthusiastically, though. Maybe no one in Leipzig has any grander expectation of an operetta or musical? Maybe putting a fake Bob Fosse number à la Chicago in satisfied entertainment needs in the outskirts of Leipzig? Maybe they don’t know better?

With one look? Lilli Wünscher and Adam Sanchez singing about babies and starting a family in “Kinokönigin” at Musikalische Komödie Leipzig, 2022. (Photo: Tom Schulze)

Stefan Klingele as conductor did make the score – in all of its rearranged Mantovani glory – sound catchy and led the huge orchestra enthusiastically. No recording or radio broadcast is planned, as the very helpful press lady of Oper Leipzig told me. And earlier plans to record the other DDR operetta Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten have also been abandoned. Which is a shame.

After this summer, there’s a change in the artistic leadership of Oper Leipzig and Musikalische Komödie. Let’s hope that the days of such uninspired operetta resurrections will be over then. And the freshly renovated house in Lindenau – with a new sound system and great acoustics – enters a new era of operetta standards others will want to copy. Jean Gilbert could certainly use that, as he was once one of the pioneers of modern German musical theatre. (For more information of Jean Gilbert’s career, click here.)

There’s a scene with an inflatable female Oscar statue in the new version of “Kinokönigin” at Musikalische Komödie Leipzig, 2022. (Photo: Tom Schulze)

By the way, Kinokönigin made it to Broadway as The Queen of the Movies (with a new book by Glen MacDonough and Edward Paulton relocating the story to Washington), Valli Valli played Delia. There was additional music by Irving Berlin.

The Broadway actress Valli Valli in the early 20th century. (Photo: www.stagebeauty.net / Wiki Commons)

In Britain, Robert Courtneidge’s staging of The Cinema Star (adapted by Jack Hulbert and Harry Graham) had Dorothy Ward playing the title-rôle. Courtneidge managed to send the show on the road, where it ran for four seasons in the UK.

Jack Hulbert! One assumes that the English version was a vehicle for Cicely Courtneidge? I have selections on two pianola rolls!

Perchè mai parlare di ‘reviving’ – qui, ormai come è ahimé consuetudine in quasi tutti i teatri – – i nuovi arrangiatori gloriano se stessi nel manipolare quel che è bello così com’è. I teatri non dovrebbero nemmeno usare più i nomi dei Compositori! Un altro esempio è YES che sta per essere pubblicato da Palazzetto Bru Zane in una nuova formazione orchestrale difficilmente da essere apprezzata da Oppicelli … Ma perchè non viene a qualcuno la voglia di ricostruire un’operetta, famosa o no, come era stata creata e assaporare quello che era veramente nell’estro degli autori, un po’ come fa la Light Opera co. dell’Ohio … ma so benissimo come è facile non essere ascoltato. Ma io non cambio idea, assolutamente no. Assolutamente NO.