Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

10 June, 2019

“More than any other art form, fashion most fully embraces and expresses camp’s exuberant aesthetic, excelling in its ability to challenge conventions of beauty and taste.” Thus begins the new catalogue Camp: Notes on Fashion, for New York City’s Costume Insitute’s spring 2019 exhibition of the same title. It’s sponsored by Gucci who write in their foreword: “The essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Of course it’s a small step from there to a discussion about operetta, since the performance practice of the genre from the 1960s onwards has been dominated by a “camp aesthetic” that celebrates the unnatural, the artificial, and the exaggerated. Only think of the camp outfits and performances of Margit Schramm, Ingeborg Hallstein or Anneliese Rothenberger, not to mention June Bronhill and others. And let’s not forget the Anna Moffo TV-films of Offenbach shows.

This camp aesthetic that dominated operetta in the “golden age” of TV films (which are available on DVD today as “classics”) has put off many. For them, this style of presenting operetta has turned the genre into something ludicrous and laughable, something that cannot be taken seriously under any circumstances. At the same time, camp in operetta has attracted – for the exact same reasons – a strong gay following. For them, camp was a set of codes they could use to deal with the subversive side of the genre in a mostly homophobic society. And get away with it!

A typical “camp” Polydor LP cover from the 1970s entitled “Das große Operetten-Wunschkonzert,” featuring an anonymous lady wearing a tiara. (Photo: Bert-Jan van Egteren record collection)

You can still see and feel that tradition in recent operetta productions by gay stage directors, such as Bernd Mottl or Stefan Huber, who gave us a glittering Frau Luna and glamorous Clivia that would put to shame anything the Costume Insitute has now put together.

Andreja Schneider as the moon goddess in Paul Lincke’s “Frau Luna” at the Tipi Zelt am Kanzleramt, Berlin. (Photo: Barbara Braun)

And only recently, Komische Oper Berlin presented Abraham’s Roxy und ihr Wunderteam as a further example of “artifice and exaggeration,” with Christoph Marti as a cross-dressed peroxide heroine on the run with 11 Hungarian football players. It made me think of an essay in the Camp: Notes on Fashion catalogue, devoted to Christopher Isherwood. There we read: “In his 1954 novel The World in the Evening, Christopher Isherwood presents camp as a dichotomy: High Camp versus Low Camp.” While the former is “the whole emotional basis of the Ballet and of Baroque art” (“a sophisticated, connoisseurial mode by which to discuss aesthetics or philosophy or almost anything”), the definition of Low Camp is this: “An utterly debased form that in queer circles connotes a swishy little boy with peroxide hair, dressed in a picture hat and a feather boa, pretending to be Marlene Dietrich.”

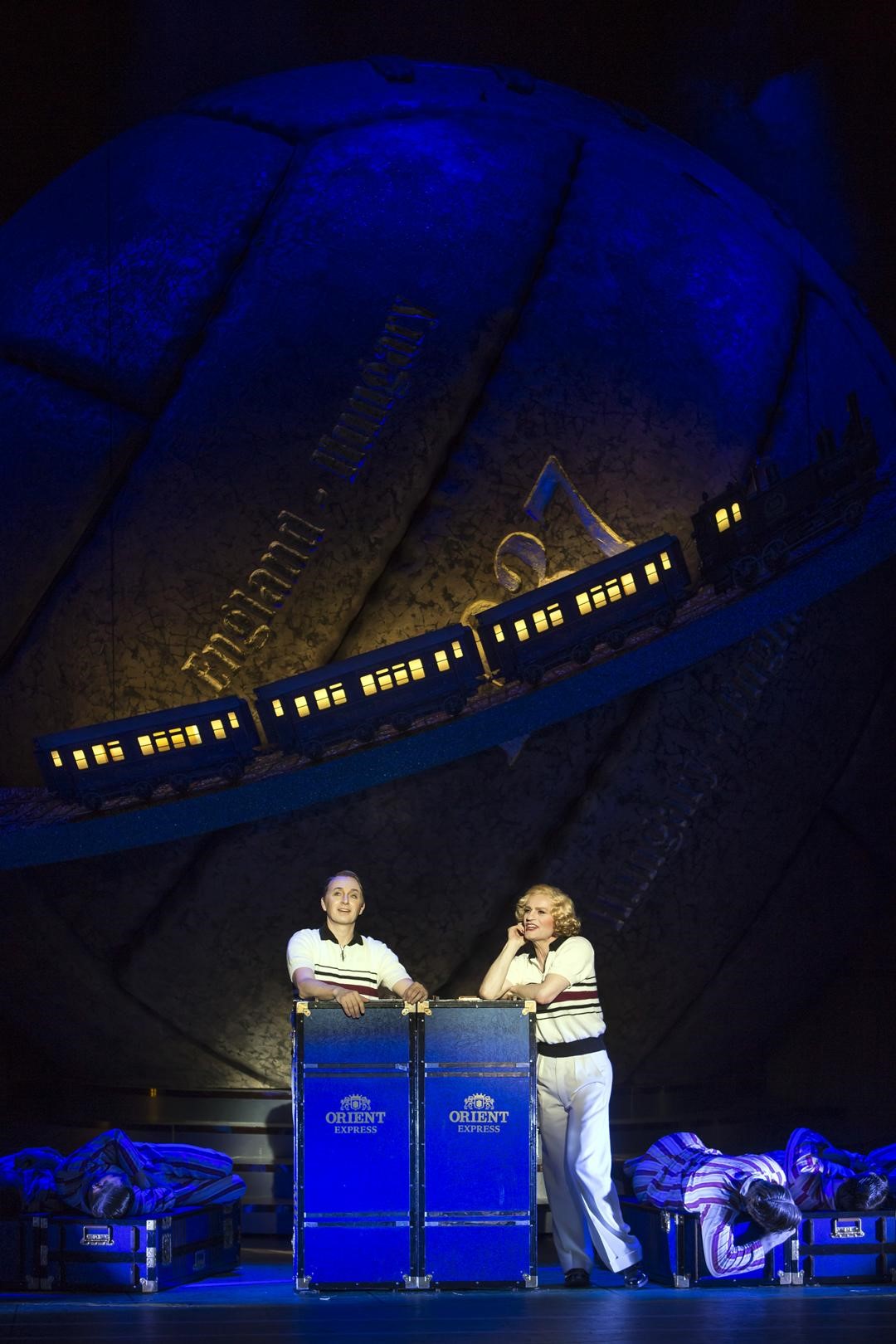

Tobias Bonn (l.) as football team captain Gjurka on the train with Roxy (Christoph Marti) in Ábrahám’s “Roxy und ihr Wunderteam” at Komische Oper Berlin. (Photo: Iko Freese / drama-berlin.de)

Well, you could argue that this almost describes Christoph Marti as Roxy, though his role model is Rosy Barsony, not Miss Dietrich.

Seeing Mr. Marti on the Komische Oper stage proved that camp – whether high or low – has arrived in Western society’s mainstream. The Costume Insitute’s exhibition is another case in point. If you watched the opening night gala with the guests arriving in the most outlandish costumes – many of these guests the stars of Ryan Murphy’s TV series Pose, about the queer ballroom culture in NYC – you could also say that camp and any form of queer camp is not subversive anymore or a secret code used by people outside the heteronormative mainstream as a form of protest and mode of surviving, it has become the mainstream. Just like RuPaul’s Drag Race. (Which is a good thing and a sign of progress, if you want to interpret it that way.)

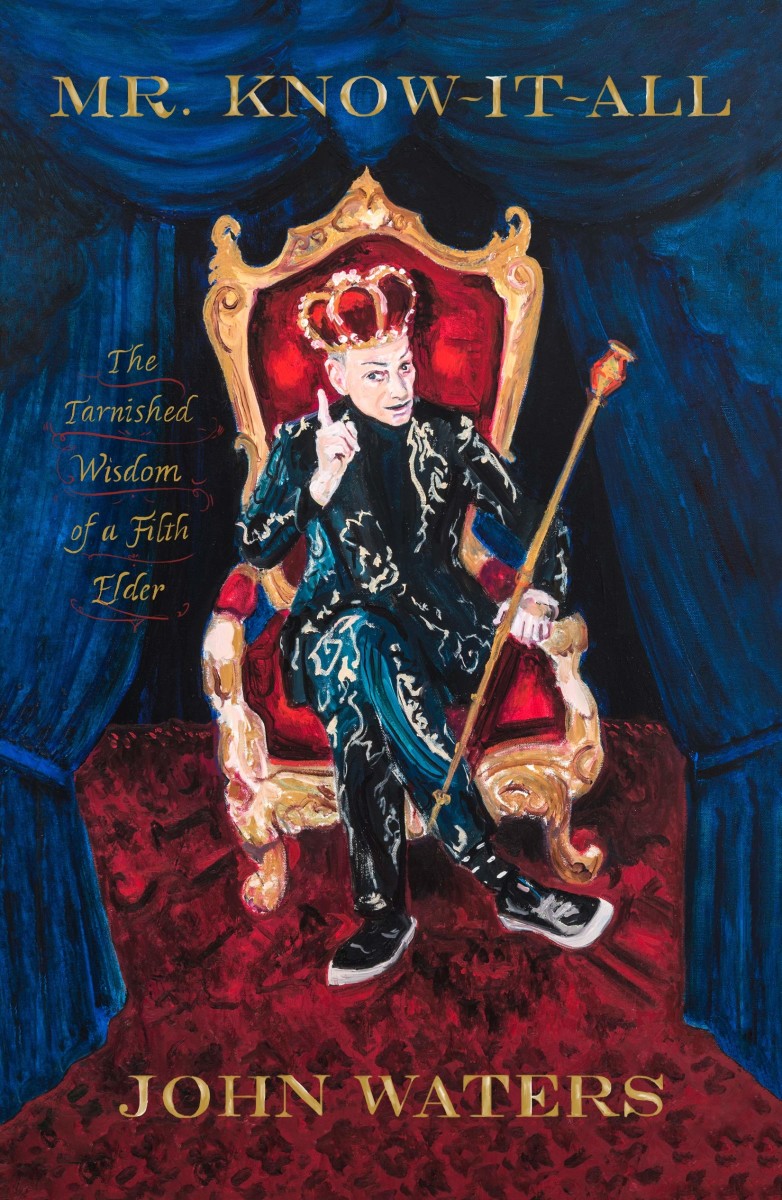

In an interview with the magazine them.use, film director and camp icon John Waters said a few weeks ago, “I think camp, trash, all those words are kind of used up — I don’t know that they have a meaning anymore.” As an alternative, he proposes: filth!

John Waters on the cover of this 2019 book “Mr. Know It All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder.” (Photo: Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

“Filth still has a punch to it, it’s a little more punk”, said Mr. Waters. “I say it with complete respect. Filth is about respecting rebellion […].” These words ran through my mind as I watched the opening night performance of Roxy, which was streamed live on the internet. In Roxy, a show written in 1936/37 as a subversive comment on Nazi ideology about superiority of the Aryan Übermensch and the moral cleanliness the Nazis propagated as an answer to the “filth and decadence” of the Weimar years, there are many songs that include lines you could describe as pretty filthy, in the best possible way. There’s the hilarious song about “The Young Girls of Today” staying at home, not going out to parties every night anymore, devoting themselves to their “lords and masters” instead – by giving them a good “hand job.” This is, on the surface, about knitting pullovers for “him.” But you could tell from the gasp coming from the audience, in 2019, that everyone understood the meaning below the surface. There was another gasp when Fräulein Tötössy tells her female students that they should be able to “spead their legs” properly in sports class if they want to get ahead in the world. The list could go on …

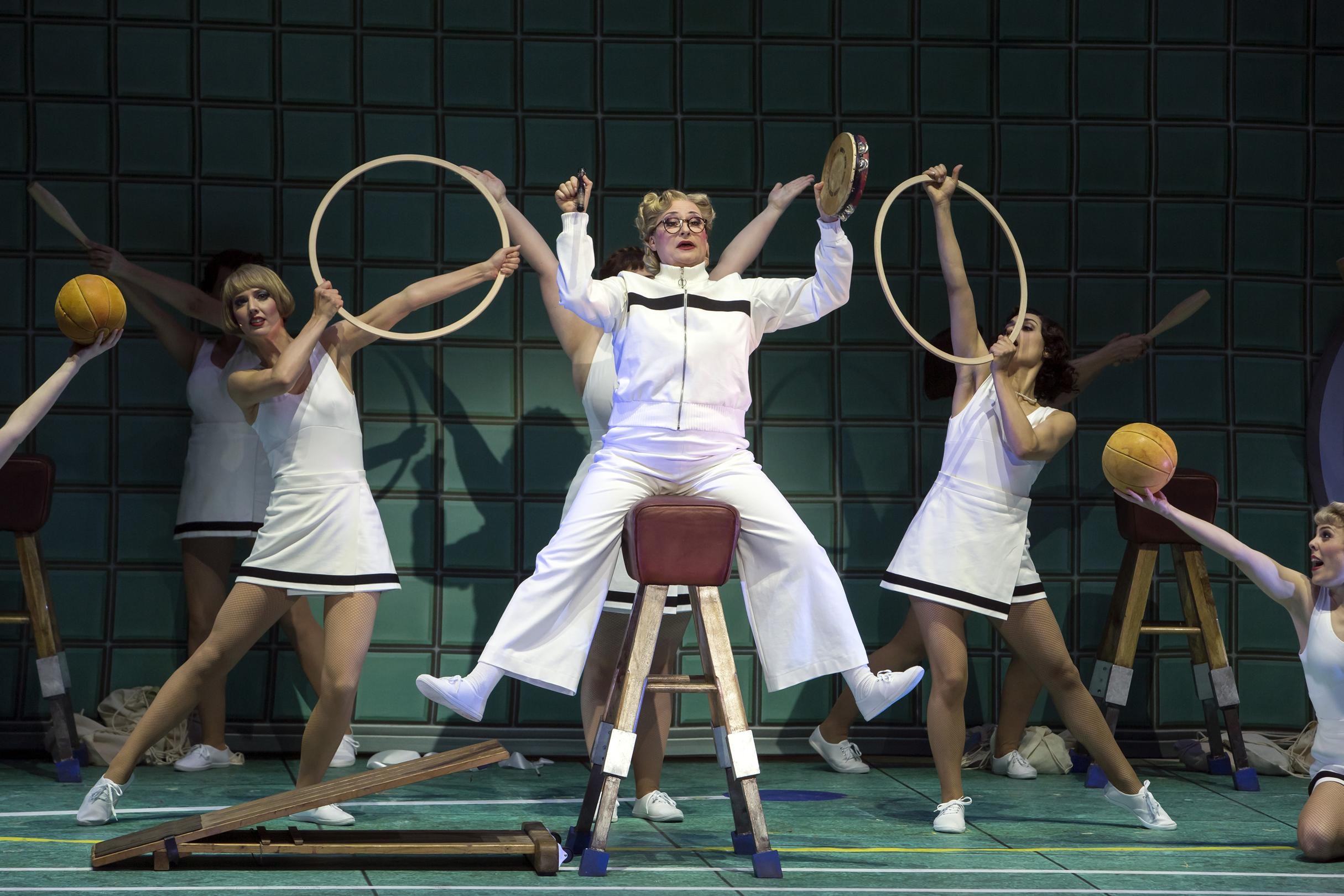

Andreja Schneider as Aranka von Tötössy, drilling her girls in “Roxy und ihr Wunderteam” at Komische Oper Berlin. (Photo: Iko Freese / drama-berlin.de)

These lines from the original German libretto by Alfred Grünwald and Hans Weigl would certainly cause an even greater gasp when delivered by John Water’s superstar Divine, emphasizing the filthy side in her own unique way. In today’s camp aesthetic the provocativeness of such lyrics and dialogue is almost anesthetized. There is no punching power left, and these moments get an amused laugh, at best. But such moments should have a sting, a political protest aspect, a fighting back element. A shock value!

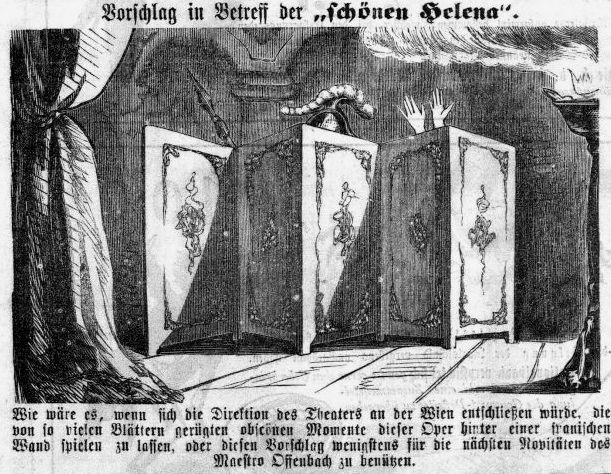

What would happen if you applied Mr. Water’s “filth” recommendation to operetta? To Abraham, to the shows from the 1920s, to Offenbach? What would Pink Flamingos meets The Merry Widow look and sound like? How would a Female Trouble approach to Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will work? How would a Polyester interpretation of White Horse Inn unfold? And it almost makes my heart miss a beat to imagine Divine playing Belle Hélène and invoking Venus – before devouring Prince Paris.

A caricature on “Die schöne Helena” in Vienna, in “Kikeriki,” 1863.

And just for the record: the Camp: Notes on Fashion catalogue actually includes an operetta! There is an entire chapter devoted to Oscar Wilde as an icon of the camp movement, and in that context you get to read about his tour of the United States to promote Patience – the Gilbert & Sullivan operetta. To see that show included, with all its queer aspects, in a Costume Insitute catalogue, is remarkable. Because usually operetta people/researchers don’t bother with fashion history, and the other way round. Here, you see how inspiring and productive it is to mix spheres. And that should apply not only to operetta and fashion, or operetta and camp.

The dragoons in “Patience” posing in the new fashion, to win back their girlfriends.

After browsing through the 180+ pages of this Camp: Notes on Fashion book, I felt a strong need to get back to John Waters. Because it’s almost too clean and safe and boring. I also felt that the article Christoph Dompke wrote in 2007 about “Zauberwort Camp” in the book Glitter and Be Gay: Die authentische Operette und ihre schwulen Verehrer needs a part 2, devoted to the magic word “filth” in operetta.

It’s the word used by so many reviewers in the 1850s and 60s when describing Offenbach shows, and their filthy side was exactly what made them so successful all over the world. It might be worth keeping that in mind for the next big Offenbach production, which is Barrie Kosky’s staging of Orphée aux enfers at the Salzburg Festival. He’s putting all singers into Swarovski underpants, to emphasize the “genital side” of the action, as an homage to Cora Pearl who appeared in the nude, as Cupid, with diamond sandals only – perhaps that’s a tad too pricy, even for Salzburg?

Famed courtesan Cora Pearl as Cupid in the “Orphée” revival, Paris 1867.

Anyway, it’ll be interesting to see how camp or filthy this Orphée will be. Or the new Grand Duchess of Gerolstein in Cologne? Can you imagine someone like Divine let loose on the soldier’s of the Gerolstein regiment – as an alternative to Jennifer Larmore who is actually playing the lusty lady in Cologne? It would even beat Régine Crespin singing “Ah! Que j’aime les militaires!”

All images by Iko Freese are from www.drama-berlin.de (Agentur für Theaterfotos).