Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

29 September, 2018

It can be exciting to re-imagine and re-interpret beloved shows: we are witnessing this, again and again, in modern musical comedy. It keeps commercial titles alive and interesting for new (and old) audiences. The latest well-publicized example is a production of Sondheim’s Company in London where the lead role of Bobby has been recast, for the first time ever, with a woman, giving the relationship-chaos-show a new dimension that has set the show queen community abuzz. Operetta producers have often been equally daring. Take Emmerich Kalman’s Csardasfürstin as an example: when it travelled to Broadway it got an entirely new book and was presented as The Riviera Girl with extra songs by Jerome Kern. Which was standard procedure back then. Back in German language realms, Csardasfürstin received a makeover in 1930 when Kalman agreed to having his score jazzed up for a Berlin production starring Rita Georg and Hans Albers. This production introduced the tango “Heut’ Nacht hab’ ich geträumt von dir” as a new tenor solo. Later Kalman gave his blessing to a revue version of Csardasfürstin in 33 scenes, the music re-arranged in Bossa Nova style. Fritz Fischer was in charge of this successful staging that toured Germany in 1951. After countless other re-writes – large and small – we now get a new version at Volksoper Wien, directed by Peter Lund, based on his own mildly re-written libretto and a score that has been moved forward from 1915 to the mid-1920s.

Elissa Huber as Sylva Varescu in “Csardasfürstin” at Volksoper Wien, 2018. (Photo: Johannes Ifkovits/Volksoper Wien)

What struck me most while watching the performance on TV (it was, for a while, also available on YouTube) was the casting. We get German soprano Elissa Huber in the title role of Sylva Varescu. According to her biography Miss Huber gave her debut in Jonathan Larson’s rock musical Rent. She went on to play in Sister Act in Hamburg and then in Zurich she starred in the juke box musical Ich war noch niemals in New York. She also did a tour production of the musical Elisabeth. She then rebooted her career and became an opera singer, performing roles such as Agathe in Freischütz. Given these credentials, I thought: ‘Wow, if you’re going to move Csardasfürstin to the Charleston Age and treat the music and lyrics in a new way then Miss Huber is it, absolutely!’

Elissa Huber (Sylva Varescu), Lucian Krasznec (Edwin), Wiener Staatsballett in “Csardasfürstin” at Volksoper Wien, 2018. (Photo: Alfred Eschwé)

That you can treat Sylva’s music differently than Anna Netrebko has been demonstrated by none other than Fritzi Massary, who scored a major success with Csardasfürstin in Berlin in 1916; her recordings of ‘Jai [sic] Mamam,’ ‘Ganz ohne Weiber geht die Chose nicht,’ and ‘Ja, so ein Teufelsweib’ have been released on CD with an intro by Robert Wennersten. (Who is currently writing a new English language Massary biography.) These tracks prove how wonderful the Kalman music can sound when a chansonette voice with great temperament and linguistic brilliance dives in. (Massary’s ‘Teufelsweib’ rendition should be required listening to anyone interested in Kalman and the ‘Hungarian’ flavor of his music.)

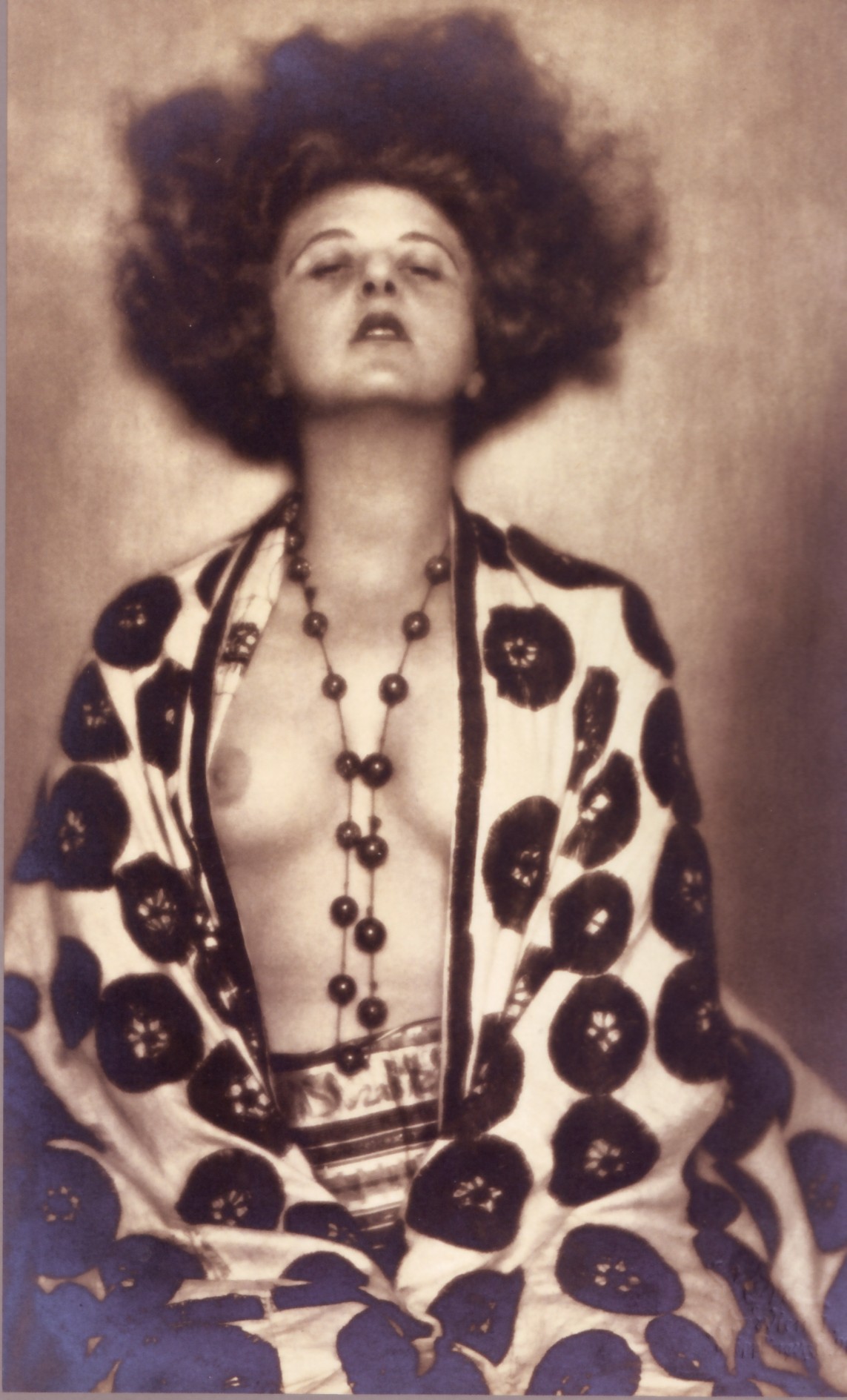

So what happens when Miss Huber finally comes onto the stage in this Peter Lund version: like a ghost from the past emerging from fog through castle walls that break open? She’s wearing the famous 1922 Elsie Altman outfit, captured by photographer D’Ora, but without exposing her bare breasts. After all, we’re living in an age of neo-prudery.

Elsie Altmann photographed by D’Ora 1922.

And then she starts to sing, not like a woman who once starred in rock musicals, but like an Anna Netrebko double: grand tones, grand vocal gestured, secure top notes, no tonal flexibility, no playing with words or phrases. It’s singing-the-notes-as-they-come; one style fits all. I was a little shocked by this. Mostly, because Miss Huber is a very convincing stage presence with her red wig and glittery burlesque costumes. As the evening progresses she doesn’t vary her style; it stays the same throughout. And that, sadly, also applies to her acting and her way of delivering dialogue. Combined, it all makes this supposed star attraction from the Orpheum in Budapest, who challenges the stuffy social conventions of her age, one-dimensional. Miss Massary, back in the day, offered layer after layer of contrasting emotion. And this assessment is based on only three tracks on a CD, can you imagine her entire live performance?

By Miss Huber’s side is young Romanian tenor Lucian Krasznec as a dishy Edwin in long white underwear, later in uniform and then in a tux. He too applies one-style-fits-all to Kalman, whether he’s singing grand operatic phrases such as “Weißt du es noch” or silly little ditties like “Das ist die Liebe, die dumme Liebe.” It’s amazing that conductor Alfred Eschwé did not create a singing style with his two main soloists that fits the new score he has the orchestra play – and that’s a very full orchestra in grand symphonic tradition, not a 1920s dance band.

In Mr. Krasznec’s biography we read that his prior experiences include Ferrando in Così fan tutte, Belmonte in Entführung aus dem Serail, Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni, Sänger in Der Rosenkavalier, Nemorino in L’elisir d’amore, Alfredo in La Traviata as well as the title role in Gounod’s Faust. That’s heavy duty lyrical tenor stuff, but it does not necessarily qualify you to sing operetta, let alone Csardasfürstin where the tenor has no solo, except the later-added „Heut‘ Nacht hab‘ ich geträumt von dir.“ Mr. Krasznec sings this right after the duet with cousin Stasi, without much tango feeling, but with heart-felt sincerity. (Is the message of that tango really so ‘heart-felt’?) He sounds great moving into the higher tenor regions. And he’s suitably juvenile to portray a young man wanting to break away from family traditions and conventions. But his well-acted portrait needs more vocal shading, no matter how nice he looks in underwear.

The only one who offers great acting, clear character singing and a style that steps out of conventional ‘operetta’ is Juliette Khalil as Anastasia Komtesse Eggenberg. She’s also the only one whose scenes – with Edwin and later with Boni Graf Káncsiánu (Jakob Semotan) – are funny: comedy scenes as they should be! As are the scenes between Edwin’s parents, the count and countess ‘von und zu Lippert-Weylersheim,’ played by Sigrid Hauser in a big white wig and Robert Meyer who does his usual thing without much variation. But Miss Hauser and Mr. Meyer basically remain stately instead of full-blown farcical. If you’ve seen Alles Schwindel directed by Christian Weise you know what I mean: there are better ways of presenting social farce; and Leopold Maria and Anhilte are a social farce!

Christian Graf (Eugen Baron Rohnsdorff), Elissa Huber (Sylva Varescu), Jakob Semotan (Boni), Juliette Khalil (Stasi), Robert Meyer (Leopold Maria, Fürst von und zu Lippert-Weylersheim), Sigrid Hauser (Anhilte von und zu Lippert-Weylersheim) in “Csardasfürstin” at Volksoper Wien, 2018. (Photo: Barbara Pálffy/Volksoper Wien)

From many details in the production I’d say that it was Peter Lund’s intention to show such a social farce. But in the end it’s not clear what he’s poking fun at. He’s moved the action to a stiff-upper-lip society in Austria, 1920s. But after WW1 aristocratic titles were revoked there, the whole aristocratic system was in crisis. What that means – and why, as a result, the Lippert-Weylersheims might act so strange – is not explored in this staging. Hints at the grotesque (e.g. in the way the engagement banquet guests are shown) are never more than hints. Perhaps the Volksoper management stopped Mr. Lund from going further? Perhaps the soloists the Volksoper gave him were not able to go further?

The aforementioned musical update mostly affects the dance evolutions. Personally, I enjoyed hearing the dance numbers expanded, and I like the Charleston style that Kalman himself later explored in Herzogin von Chicago. (In a much more radical fashion, it might be noted.) What struck me was how little choreographer Andrea Heil bothers with details of the plot. Even in the emotional breakdown moments of the act 1 finale, when Sylva learns that the engagement with Edwin is a sham and that he’s already engaged to someone else – Miss Heil has Sylva and her two bosom buddies Boni and Feri Bácsi (Boris Eder) delve into a quick step, as if nothing had happened and they needed to go on with the show. While a chorus line jumps around in the background. I guess that’s one way of ‘updating’ operetta.

The show itself, with its black and white colors and film clip moments, is reminiscent of Lund’s successful production of the Hollywood satire Axel an der Himmelstür. His stars from that Benatzky show, Andreas Bieber and Bettina Mönch, might have proven better choices for this update of Csardasfürstin than typical opera singers unfamiliar with the finer (or broader) details of operetta. But that’s only a guess.

The local Online-Merker wrote about the production after opening night: “After the two big flops in the past years this Csardasfürstin is finally an operetta production that is convincing and lives up to the tradition of the house.” (“Mit dieser Csardasfürstin ist der Volksoper nach den beiden veritablen Flopps im Vorjahr endlich wieder eine Operettenproduktion gelungen, die der Tradition des Hauses entspricht.”) Reading this made me slightly wonder how the Austrians define ‘tradition’ – and what the ‘tradition’ of the Volksoper is? (And whether it’s really worth saving if this is an all-round positive example of it.)

Considering the more radical alternations that have been made to Csardasfürstin on Broadway, or to Company in the West End, I would have enjoyed a more daring new version of the Kalman evergreen. If you’re just going to move a few snippets of text and music around, why not stick to the successful original in the first place? (I suppose everyone wants a piece from the royalties cake.)

I wonder if the filmed performance that was broadcast by ORF will find its way onto an international DVD release. I also wonder if any other theaters will buy this new version and give it a second chance somewhere else, or if it’ll remain a Vienna exclusive. Time can tell. And perhaps, with time, Miss Huber, Mr. Krasznec, and all the others, will find a more nuanced and freer way to perform a ‘jazz age’ Csardasfürstin. Operetta aficionados would benefit from it!

Here is the full performance as filmed by ORF:

For further details, performance dates and tickets, click here.

Dieses berühmte Photo von Elsie Altmann kursiert auch als Bild der Nackttänzerin Anita Berber. In dem wikipedia Eintrag zu Berber heißt es, z. B.: »Bei Madame d’Ora entstanden eine Reihe von ausdrucksstarken Aufnahmen, welche damals auch im Berliner Magazin und in Die Dame veröffentlicht wurden.«

Was hat es denn damit auf sich? Da muss es doch irgendwo eine Verwechslung geben. Oder sind die Bilder von Altmann und Berber täuschend ähnlich?

Is there someone who can tell me I am wrong if I prefer DIE CSARDASFÜRSTIN as it is in its original form (as the available vocal score shows)? I know that some people loving operettas say that the important thing is that these works go on being performed – no risk how they are shown … Well, pardon me, if I enjoyed the Christian Thielemann offering of this masterpiece. Non toglietemi il saluto per questo!