Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

11 August, 2019

Considering that there are not that many new books on operetta in English, one must greet Derek B. Scott’s fresh-off-the-press German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900-1940 with a big cheer. Also, the fact that this was released by Cambridge University Press is a big plus; since it will reach a lot of students; and operetta students in the Anglo-American world can certainly use a bit a fresh inspiration to catch up on some of the things that have been examined in German language research recently.

The cover of Derek B. Scott’s “German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900-1940.” (Photo: Cambridge University Press)

This new book is clearly structured in two parts: the first is dedicated to “The Production of Operetta,” the second to “The Reception of Operetta.” In part 1 there are four subsections, entitled “The Music of Operetta,” “Cultural Transfers: Translations and Transactions,” “The Business of Operetta,” and “Producers, Directors, Designers, and Performers.” In part 2 the four sections are “The Reception of Operetta in London and New York,” “Operetta and Intermediality,” “Operetta and Modernity,” and “Operetta and Cosmopolitanism.” After 276 pages you also get a postlude entitled “The Demise of Operetta,” focusing mostly on the changes that occurred after the Nazis came to power and changed the operetta scene radically.

There are a great many facts swirling around in this book, and there are many cross-references, such as “see chapter X.” It’s not necessarily a straight-forward read with lots of intellectual buzz, as in the latest book by Laurence Senelick on Offenbach for example, also at Cambridge University Press. Mr. Scott is more busy presenting material, rather than interpreting it or coming up with novel ideas about the why and wherefore of operettas crossing from Berlin and Vienna to New York and London.

But that is perfectly okay. There is room for dry-ish data, especially when it’s useful to have, as this certainly is.

Book cover “Popular Musical Theatre in London and Berlin.”

The book expands the horizon from the earlier Popular Musical Theatre in London and Berlin, 1890 to 1939, edited by Len Platt, Tobias Becker and David Linton. This also came out at Cambridge University Press in 2014 and includes a chapter by Derek Scott with a near similar title: “German operetta in the West End and on Broadway.”

I am not entirely sure why the analysis in the new book starts in 1900 and why the works of Franz von Suppé are left out. After all, his Boccaccio premiered in Vienna in 1879 and made quite a splash in America where it came out at Union Square Theatre in English in 1880 (after a German language premiere at the Thalia Theater earlier the same year); Boccaccio also ran in London at the Comedy Theatre in 1882. I recall an article by Kurt Gänzl in Welt der Operette (Theatermuseum Wien) about this Suppé show being the most internally successful of all 19th century Viennese operettas from what we today like to call the “Golden Era,” i.e. the time of Suppé, Strauss, Millöcker et al.

But Mr. Scott’s focus is more on what is now labeled “Silver Era” operetta, and there is enough to digest there, even without Suppé. So I am not complaining.

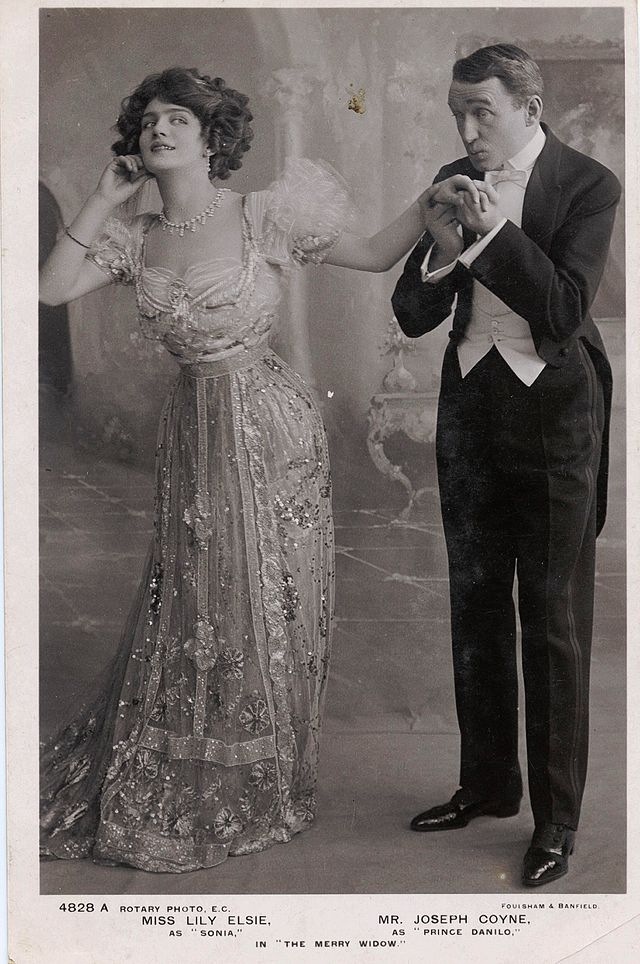

Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne in “The Merry Widow.” In its English adaptation by Basil Hood, with lyrics by Adrian Ross, the show became a sensation at Daly’s Theatre in London, opening on 8 June 1907.

When we leave the mere lists of facts and historic dates and get to sections such as “Moral Questions Raised by Operetta” and read about the Merry Widow in London in a journal by Arnold Bennett (1910) claiming that it’s “all about drinking, and whoring and money” my personal interest was triggered. But the discussion of such aspects is comparatively short. And that includes the general discussion of “Modernity and Sexuality” which mostly focuses on Leo Fall’s Die geschiedene Frau. (Why that show and not many others?) At the end of this sub-chapter the focus shifts to “queering the production and consumption of operetta.”

Since I am quoted there with my own Glitter and Be Gay (2007) I was very curious to read what there might be to say in English about LGBTIQ operetta. But it’s basically a mini-mini-section that’s over before any discussion properly begins.

But I am very thankful to Derek Scott for including my Glitter and Be Gay and so many other recent publications in his book and pointing a way which future researchers might take.

There are expansive appendixes that are useful to have, too. The first is a listing of all productions of operetta from the German stage on Broadway and in the West End, 1900-1940. It starts with Abraham and ends with Robert Winterberg (Die schöne Schwedin, Die Dame in Rot) and Carl Ziehrer.

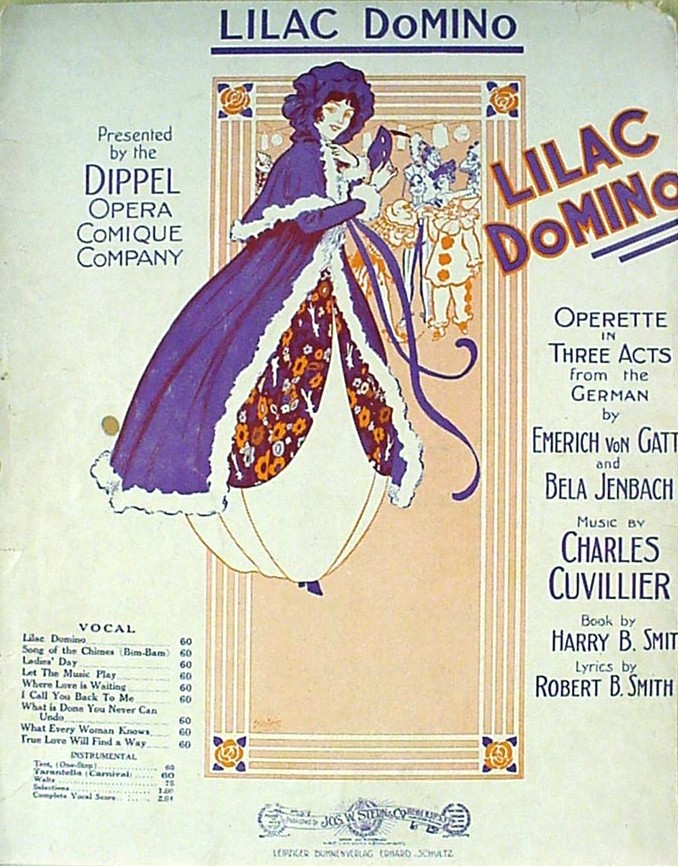

Then there is a “Broadway Top 20” and a “West End Top 20” with numbers of performances. No. 1 on Broadway is the Berté/Schubert/Romberg Dreimäderlhaus/Blossom Time (516 performances), followed by The Merry Widow (416 performances). In London no. 1 is the Widow with 778 performances, followed by Cuvillier’s 1918 The Lilac Domino (747 performances).

Sheet music cover for Charles Cuvillier’s “Lila Domino.”

Then there is an appendix on the operettas with English librettos by composers for the German stage, starting with The Eternal Waltz at the Hippodrome, music by Leo Fall, and ending with Kurt Weill.

There is also an appendix on “Selected Period Recordings of English Versions of Operetta from the German Stage.” I’d be very curious to know if Mr. Scott actually posses all the recordings he lists – and if there is any chance that they might be released on CD sometime soon.

Erich von Stroheim with his two stars, Mae Murray and John Gilbert, shotting “The Merry Widow,” 1925. Miss Murray is seen here in her “showgirl” costume.” (Photo: Archive Operetta Research Center)

The next appendix is about “Selected Films in English of Operettas by Composers from the German Stage.” And, yes, we start here with Merry Widow and Mae Murray/John Gilbert and Maurice Chevalier/Jeanette MacDonald. I was surprised to see Jean Gilbert’s The Lady Ermine (1927 and 1948) there, as well as Millöcker-Mackeben’s Die Dubarry with Gitta Alpar, apparently filmed in 1936.

As a last appendix there is a list of “Research Resources” and websites, the Operetta Research Center gets a mention here too. (Thank you, again!)

My only serious reservation about the new book are some blatant editing mistakes that caught my eye without especially looking for them; I would have expected a publisher such as Cambridge University Press to double check who wrote Der Opernball (it’s not Heinrich Reinhardt as is stated on page 21). And Das Veilchen vom Montmartre was not written by Lehár, but by his most immediate competitor, Kálmán (p. 31).

Lobby Card for the movie version of “Golden Dawn”.

And if you mention Kalman’s Broadway operetta Golden Dawn (1927) – which I think is wonderful, because it deserves more attention – then the composer Kalman collaborated with was Herbert Stothart, not Hubert (p. 204). By the way, to say that Kalman’s “grasp of syncopation was slight at this time” is somewhat astonishing since he wrote Die Herzogin von Chicago a year later!

Perhaps Cambridge University Press can clean up some of these errors before this book goes into wider university circulation. And I hope Derek Scott will expand on some of the topics he discusses in the subsections, because they are really interesting and worthy of broader analysis.

Prof. Derek B. Scott from the University of Leeds. (Photo: Private)

When Mr. Scott organized his big operetta conference in Leeds in January 2019 he invited many speakers who elaborated on various of these points. And since this is such a huge field of research it might actually be better to have a collection of essays from different authors rather than expect one person to cover everything.

That said, this is not the Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre, instead it’s a slim 380 page book that gives a clear overview of this particular field, as a good introduction that mentions many important aspects that will give students more than enough to do on their own in the years to follow.

I am very honored to have received a signed personal copy from Derek. So one last time: thank you!

An interview with Derek Scott about new perspectives in operetta research can be found here.