Kevin Clarke / Kurt Gänzl

Operetta Research Center

5 April, 2020

With all this free time at home right now I’ve started working my way through various DVD boxes I’ve had for ages, containing films I never watched. This week I finally got around to an Alice Faye DVD edition, and the title that caught my immediate attention there was a film called Lillian Russell. Why? Because the cover looked like a Mae West movie and like the prima donna vehicle this film certainly turned out to be. As I watched the story of Lillian Russell unfold on screen I was surprised to find a New York production of Grand Duchess mentioned, and Gilbert and Sullivan popping up as characters. Aha, I thought: a 19th century operetta diva I hadn’t heard of before. When I checked Miss Russell’s biography on Wikipedia I was stunned that the movie had edited out almost all the “juicy” bits (bigamy, prostitution in the theater, anything reminiscent of #metoo debates etc.) Needless to say, my curiosity was tickled.

Poster for the 1940 movie “Lillian Russell.” (Photo: 20th Century Fox)

Especially when I found out that the famous scene in which Lillian Russell sang for the President of the USA via Alexander Bell’s long distance telephone from New York in 1890 was Offenbach’s Sable Song from Grande Duchesse de Gerolstein – and not the number used in the movie. And also when I read that Marilyn Monroe was photographed as Lillian Russell by Richard Avedon as part of a series called Fabled Enchantresses, published in Life magazine in December 1958. How did all of that escape me so far?

Marilyn Monroe photographed as Lillian Russell by Richard Avedon, published in “Life” magazine in December 1958. (Photo: Life / screenshot)

The Wikipedia biography is quite expansive, with wonderful details. Also, the comments on the International Movie Data Base are fascinating (“dullest biographical film ever made”, “overly sentimental”, “lush and fluffy”, ” The facts of the story may be wrong, but who cares” etc.)

So I thought I’d ask Kurt Gänzl what he has on Miss Russell. His reply is this: “Much of what has been written (and filmed) about her is fiction. I studied her deeply when I was preparing a book on her husband Teddy Solomon … I have/had some of her letters …. Her importance has been somewhat exaggerated because of her looks and mini scandals … she has become a ‘name’ … witness the film. But she’s still fun!”

Lillian Russell in 1905. (Photo: Benjamin Falk)

Indeed, she is. And in many ways her career is typical of other famous operetta divas from the 19th century, be it in Paris or Vienna. So I think it’s worth presenting Helena Louisa Leonard afresh, the woman born on 4 December 1860 in Clinton, Iowa, who died in New York in 5 June 1922 and was “America’s queen of comic opera in the last decades of the 19th century”, a “buxom beauty of early 20th-century Broadway burlesque.” By comparison, the Alice Fay version of her life is closer to the original than, let’s say, Maria Holst in the movie Operette by Willi Forst (also 1940) is to what we know of Marie Geistinger. Who, by all accounts, had a career not dissimilar to Miss Russell. They even shared various roles by Offenbach, Millöcker and others.

Marie Geistinger as Offenbach’s Helena, one of her greatest theatrical triumphs.

All of these leading ladies are deserving of a new biopic that openly addresses what made their careers so “modern” by today’s standards, revolutionary even. It’s certainly high time to blow away the dust of nostalgia and get to the “real” operetta stars behind the prude Hollywood facade or, worse still, the anti-Semitic Nazi facade in the Forst movie.

So let’s hear what Mr. Gänzl has to say about Helena Louisa Leonard who became the one-and-only Lillian Russell:

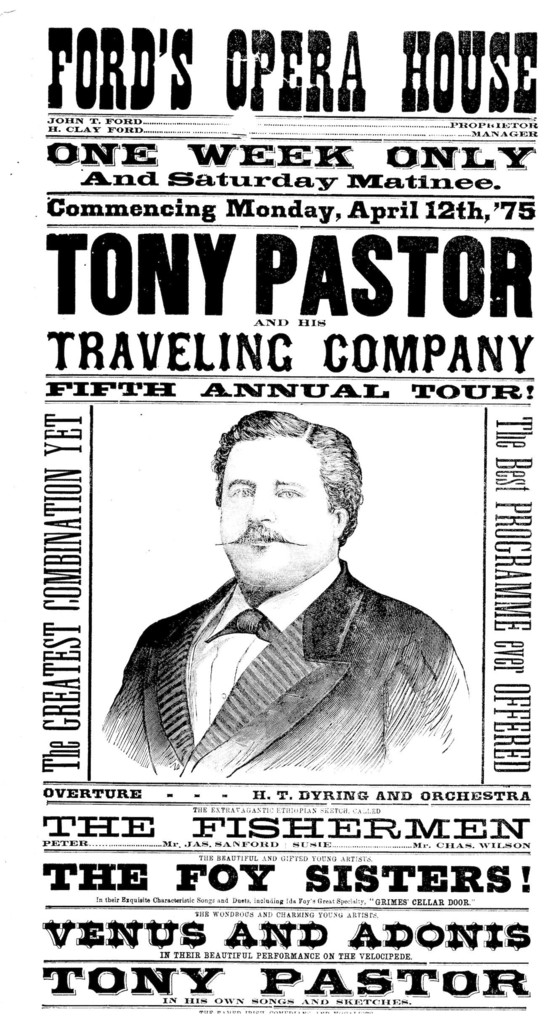

One of the five daughters of a profitable printer, Charles E Leonard (of Knight & Leonard) and of Mrs Cynthia Leonard (d Rutherford, NJ 9 April 1908), a well-known women’s rights campaigner, the young Miss Russell was convent-educated in Chicago and went to New York at the age of 16 to study singing with Erminia Rudersdorff. Before long she was appearing in the chorus of E E Rice’s touring HMS Pinafore (with which she played a single week on Broadway) and Evangeline companies and married (briefly) to Harry Braham, the company’s musical director. The shapely young soprano soon won engagements as a solo vocalist, and appeared at Tony Pastor’s variety theatre as a ballad singer with a success which soon merited her the leading rôles in the house’s burlesque production of The Pie-Rats of Penn Yann (1881, Mabria ie Mabel), Oily-Vet (1811, Olivette), Billee Taylor (a burlesque Phoebe) and so forth.

Advertisement for Tony Pastor’s traveling company.

She left Pastor to go on tour with Willie Edouin’s farce comedy company and when she returned to New York it was under the management of John McCaull, newly launched at the Bijou Theater with the intention of becoming the city’s only and/or best musical theatre producer. McCaull starred the 19-year-old Miss Russell as the snake-charming Irma (here called Djemma) opposite Selina Dolaro in his production of Audran’s Le Grand Mogol (The Snake Charmer) and she compounded this success as Bathilde in a production of Les Noces d’Olivette (Olivette) before returning to Pastor’s in January 1882 for more Patience and more Billee Taylor. She departed again to organise her own production of Patience (June 1882) with McCaull at Niblo’s Theatre. Patience was a 92-performance success for the popular young star, already hailed as ‘The Queen of the Dudes’, and she and her producer followed it with another good run with The Sorcerer (Aline, 1882). However, just when she should have been ready to follow up her English operetta sucesses with a piece written specially for her by the composer of Billee Taylor, the dashing Teddy Solomon, she fell ill. The illness caused a furore in dude-land, and as the newspapers daily chronicled the fair prima donna’s slow progress to health, the production of Virginia, without its prima donna, ran through five Broadway weeks.

Lillian Russell in 1890.

Miss Russell made her return to the theatre in breeches as Prince Raphaël in La Princesse de Trébizonde (Casino Theater), but she walked out after three weeks, in an early example of the cavalier attitude to contracts which was to speckle and damage her career, to follow Solomon to Britain and escape her forthcoming contractual obligations to the Standard Theater. After some characteristic lack of legal co-operation between the British and American courts, she was permitted to appear in Virginia (retitled Paul and Virginia) at the Gaiety Theatre, but although she won some nice personal notices, the show was quickly over. She then signed to appear in comic opera for Alexander Henderson but was released by him to create the rôle of Princess Ida for Carte. However, her unwillingness to rehearse and her generally unprofessional attitudes resulted in her being dumped by the no-nonsense Savoy.

1882 photo of Lillian Russell in the Bijou Opera House production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Patience.” (Photo: Anderson)

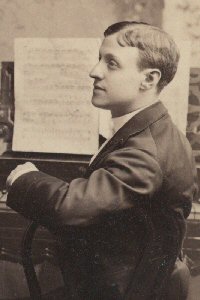

This time it was she who squealed ‘contract’, but to no avail, and before long she and Solomon were off to Europe with a tour of Billee Taylor. They dropped out after a few weeks, leaving the tour to wander on and become stranded, and came back to Britain where, later in the year, they at last had success together as star and composer of Polly, the Pet of the Regiment. When Lillian played Solomon’s version of Pocahontas they were less successful, and the duo promptly switched their field of action back to America. There they did rather better with Polly and another new piece, Pepita, before coming to a dramatic break-up in their ‘married’ life when it was revealed that the composer – whose attitude to contracts was pretty much the same as that of his ‘wife’ – was a bigamist.

Composer Edward Solomon in 1875.

Solomon went back to face charges in a British court (he was sent to prison), Lillian remained in America to play for John Duff, appearing in her ex-almost-husband’s The Maid and the Moonshiner (1886, Virginia), in the title-rôle of Dorothy, as Inez (and later Anita) in The Queen’s Mate, as Princess Etelka in Nadgy, Fiorella in The Brigands, in the title-rôle of The Grand-Duchess, as Harriet in Broadway’s version of Poor Jonathan and as Pythia in Apollo (Das Orakel).

Lillian Russell in Offenbach’s “Les Brigands.”

She starred in the American production of Audran’s La Cigale and as Teresa in The Mountebanks, and took out her own touring company with these last two pieces, before returning to Broadway to play Giroflé-Girofla and the rôle of Rosa in the American comic opera Princess Nicotine.

Lillian Russell in “Giroflé-Girofla” in 1895.

Miss Russell made her first return to England since her ‘divorce’ to play at the Lyceum in a specially organized production of Edward Jakobowski’s Austrian success Die Brillantenkönigin (1894, The Queen of Brilliants, Betta) which was using London as a springboard to Broadway, but the show was a failure and — in spite of the announcement of all kinds of new and original musical vehicles, including a Ludwig Englander piece which would have starred her as Cleopatra - she returned to the safety of Offenbach to star on Broadway in another Hortense Schneider rôle as La Périchole.

“The Dressing Room of Hortense Schneider,” 1873. Painting by Edmond Morin.

Over the next few years she also appeared in revivals of Le Petit Duc, Patience and La Belle Hélène, but a series of new home-made musicals (The Tzigane, The Goddess of Truth, An American Beauty, The Wedding Day) did not find her the original rôle which had eluded her throughout a long and otherwise remarkable career.

After appearing in a revival of Erminie she turned, with the century, back to burlesque and the last part of her career, with the exception of a 1904 sally forth to appear as Lady Teazle in a comic opera of that name, was spent at Weber and Fields’s place of entertainment, appearing in the revusical concoctions produced there (Whirl-i-gig, Fiddle-Dee-Dee, Hoity-Toity, Twirly Whirly, Whoop de doo, Hokey Pokey). If these naturally did not produce the elusive rôle, Twirly Whirly did produce the only song since Solomon’s ‘The Silver Line’ (which she had, in any case, not created) to which Miss Russell’s name would stay attached, John Stromberg’s ‘Come Down Ma Evenin’ Star’. Her appearance in Hokey Pokey in 1912 was her last on the Broadway musical stage, except for an ‘appearance’ in song in the 1914 The Beauty Shop when Anna Orr gave out with Charles Gebest’s ‘I Want to Look Like Lillian Russell’. Presumably she meant the Lillian Russell of a year or two earlier in time.

Lillian Russell – or what she represented – has been portrayed on stage and film a number of times. A London rewrite of Sally (1942) managed to introduce her into the proceedings in the person of the buxom Linda Gray (soon after to be Queen Elizabeth I in Merrie England and later London’s Domina in A Funny Thing …), but Hollywood devoted an entire 1940 film to her in which she was portrayed by Alice Faye. Andrea King (My Wild Irish Rose) and Binnie Barnes (Diamond Jim) were other screen Lillians.

Miss Russell’s sister, Suzanne Leonard, played in minor rôles in her company in the 1890s.

Biography: Morell, P: Lillian Russell: The Era of Plush (Random House, New York, 1940), Burke, J: Duet in Diamonds (Putnam, New York, 1972), Schwarz, D R & Bowbeer, A A: Lillian Russell: a bio-bibliography (Greenwood, Westport, Conn 1995); Fields, A: Lillian Russell (McFarland, New York, 1999)

The legend of “Come down ma evenin’ star” is quite well known. Joan Morris and her husband, William Bolcom, included it on one of their retrospective albums. The story, as I have it, is that John Stromberg wrote the song for Lilian and then committed suicide. Ms. Russell made sure that the audience was well aware of that situation and, of course, there was never a dry eye in the house when she performed it.