Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

19 September, 2020

What grabbed my immediate attention with this new Eine Nacht in Venedig on cpo are the names on the cover: in equal size we find Johann Strauss and Erich Wolfgang Korngold mentioned, side by side. And on page one of the booklet there are two photographs of these two gentlemen, again in the exact same size, next to one another. With the notice, that this CD presents the operetta “in the musical version” by Korngold and the “libretto version” by Ernst Marischka (who became very famous in post-WW2 times as the creator of the Sissi movies with Romy Schneider).

The cast album “Eine Nacht in Venedig” from Oper Graz. (Photo: cpo)

This packaging of Nacht in Venedig suggests something new, something possibly in line with the recent revived interest in Korngold’s other operetta adaptations. You’ll recall that Musikalische Komödie in Leipzig dug up Das Lied der Liebe (based on Johann Strauss) and Rosen aus Florida (based on Leo Fall), they released their productions with the label Rondeau. Is cpo following that trend, after having released various Korngold rarities themselves? (For a full account of Korngold’s operetta activities, click here.)

A gondoliere in Venice. (Photo: Marco Secchi / Unsplash)

While the aforementioned works did not exist in full recordings, just like many other famous Korngold operetta re-workings such as Fledermaus (created for Max Reinhardt in Berlin) are not available as recordings, the case of Eine Nacht in Venedig is different. Because this 1883 Strauss hit exists almost exclusively on record in the version Korngold created in 1923 for Theater an der Wien. One usually recognizes it, at first glance, because the star tenor gets to sing “Sei mir gegrüßt, du holdes Venezia” and “Treu sein, das liegt mir nicht” – both are extras created by Korngold/Marischka for Richard Tauber who ventured into operetta territory for the first time in 1923 as the Duke of Urbino. Originally, the Duke was only a minor role, since the show centered around the comedians playing Caramello and Pappacoda, so Tauber’s part was given more musical weight and the whole piece was shifted from slapstick to a more sentimental tenor “showcase.”

The new recording comes from Oper Graz in Austria, but the production itself originated in Lyon, France. Conductor Marius Burkert wrote to me that cpo was explicitly looking for the Korngold version, and dramaturg Bernd Krispin discusses that Korngold version at length in the booklet. What he doesn’t mention – and what cpo does not tell us on the cover – is which Korngold version we’re actually getting. The 1923 update is pretty well-known and has been extensively recorded – from Schwarzkopf/Ackermann and Schock/Marszalek to Wunderlich/Walter and Gedda/Allers – while Korngold’s second expanded version of 1929 has not yet been put on disc. It’s the version in which Eine Nacht in Venedig entered the Vienna opera house with Maria Jeritza, Adele Kern, Lillie Claus, Hubert Marischka, Josef Kalenberg, Alfred Jerger and Koloman Pataky. (You could call that luxury casting of the highest possible order.)

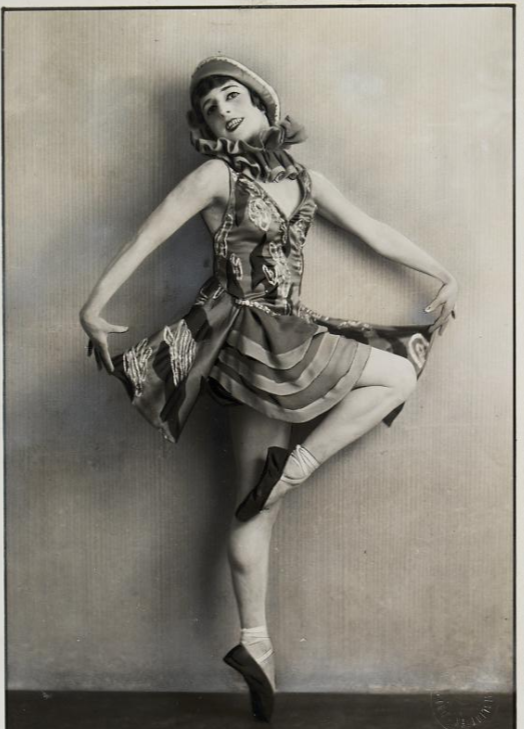

Maria Jeritza in “Eine Nacht von Venedig,” 1929. (Photo: Atelier Dietrich / Theatermuseum Wien)

Hubert Marischka – then director of Theater an der Wien, Kalman’s leading man of choice, brother of Ernst – was the first operetta-star-who-wasn’t-an-opera-singer to set foot on the stage of the Staatsoper. The magazine Das kleine Blatt wrote about him: “He articulates his text clearly, creates humor and temperament, and he is not afraid to shake the holiness of the house with a few vulgar jokes. The others are a little too stiff by comparison.” The magazine Adaxl ads: “Marischka surprises with powerfully sung notes, he uses all layers of his lovable personality with virtuosity, and he has the advantage over most opera singers that he handles his text carefully, is a model dancer and demonstrates great confidence in all of his movements.“ Something Marischka had in common with Alexander Girardi who created the role in Vienna in 1883, as the productions main attraction.

Hubert Marischka as Caramello in “Eine Nacht in Venedig,” 1929. (Photo: Atelier Dietrich / Theatermuseum Wien)

Apart from the casting, the biggest different between the 1923 and 1929 versions are the newly arranged dance sequences that allowed for an opulent staging, some were even spiced with a few jazz elements. After all, we’re at the height of the Roaring Twenties.

Adele Krausenecker in “Eine Nacht in Venedig,” 1929. (Photo: Atelier Dietrich / Theatermuseum Wien)

Opening night was a triumph, even if some 1929 critics complained about innovations they considered too radical: “When right at the start a lovely Strauss waltz comes along in a ‘modern rhythm’ horror crept over the faces of lovers of Strauss music, this tasteless extra must be eliminated immediately, but the rest of the new elements was wonderful, you could even say: genius.”

Erich Wolfgang Korngold, in a newspaper caricature from 1929.

Some very modest xylophone sounds in the dance duets apart, not to mention a few swishing harp glissandi, this new cpo release conducted by Marius Burkert has nothing to do with the “horror” inducing version created for the Staatsoper in 1929, instead it turns out to be the too familiar “old” version. And creates serious competition.

Because no matter how refreshing the balanced Graz ensembles acts and sings, not a single cast member can live up to standards set by famous predecessors. Even if some singers laudably try to learn from past interpreters and copy trademarks. Lothar Odinius as the Duke for example tries a few seductive mezza-voce effects, he even allows himself a portamento here and there, but in the end he does not command the melting tones of Tauber or Nicolai Gedda, and he totally lacks that daredevil attitude that made Rudolf Schock quite irresistible (especially on the first recording under Franz Marszalek, 1953). Also, conductor Burkert does’t seem to understand that this music needs rubato and enormous tempo flexibility to fully develop its magic, something he could have learned by listening to the many role model recordings from the past.

Alexander Geller is a pleasantly youthful and silvery voiced Caramello whose entrance with a tarantella brings something like “drive” to this recording. (You are already on track 5 by then!) But truth be told: the famous “Gondellied“ was sung so much more dashingly by Fritz Wunderlich on the 1960 recording under Fried Walter. (He recored it, as a solo, several times.)

And if you think that’s an unfair comparison because no one can ever sing that better than Wunderlich, then try the 1938 complete recording from Reichssender Berlin. Even though the sound quality is stone age you get Marcel Wittrisch simply blasting away any competition, Wunderlich included. That “Komm in die Gondel” as sung by Wittrisch has so many surprising twists and turns, and in the end such outstanding glamour in the top notes, that even today I hear it and think: yes, that’s exactly how it should be done! (And Wittrisch, too, recorded this number as a solo several times.)

The third gentleman in the male lead is Ivan Oreščanin as the spaghetti cook Pappacoda. I’d describe him as somewhat “limited” where comedy is concerned. For a very different and surprising interpretation listen to the young Peter Alexander in 1953 (again under Marszalek) who demonstrates none of his later trademark mannerisms but a lot of winning ease.

There isn’t much one can say about the role of senator Delaqua, sung here by Götz Zemann, because his entire dialogue has been cut, just like all other dialogue is left out too. Which kills any sense of drama and turns this operetta into something of a “Wunschkonzert.”

That the dialogue can be fun and an important part of the show is demonstrated by Reichssender Berlin: with proper character actors (!) who stand out, each and every one of them. The 1938 scenes with the three senators (Otto Sauter-Sarto as Delaqua, Carl-Heinz Carell as Barbaruccio and Richard Senius as Testaccio) are showstoppers, and it’s amazing how these three comedians manage to slip in jokes about incapable political leaders in a performance from Nazi times. On the Graz recording you get none of that, because this entire plot element is eliminated on record.

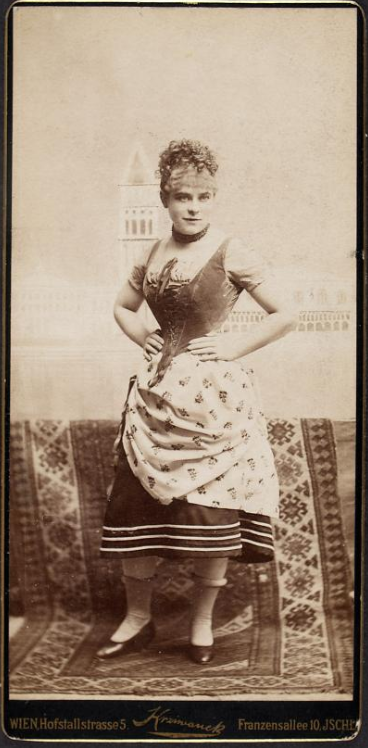

Karl Lindau as senator Barbaruccio in “Eine Nacht in Venedig,” Vienna 1883. (Photo: Anonymous / Theatermuseum Wien)

The female lead of the fish vendor Annina (sung in an unparalleled way by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf on EMI/Warner) is given to Elena Puszta. She was a slightly sour soprano which she doesn’t use for shrewd effects, because she sings her music without any audible interest in the text and character. Which makes the slightly off-pitch timbre stand out even more noticeably. Compare that to the loveliness and charm Rita Streich and Lisa Otto ooze as Annina, with perfect diction by the way.

The lack of character and proper diction might also be mentioned with regard to Elisabeth Prats leading the senator’s wives to battle (“So ängstlich sind wir nicht”), there’s none of the resoluteness and fearlessness that made Gisela Lizt so incredibly funny on the 1967 recording from Munich (conducted by Broadway’s Franz Allers.)

Rosa Streitmann in “Eine Nacht in Venedig” back in 1883. (Photo: Rudolf Krziwanek / Theatermuseum Wien)

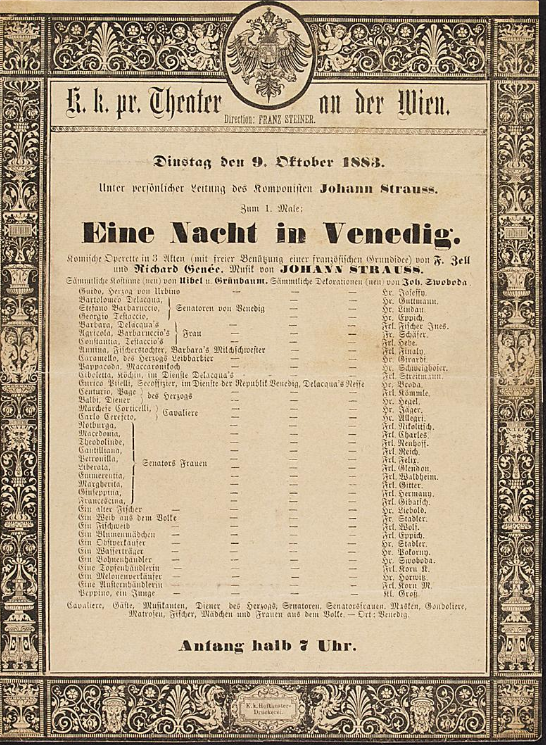

So why release this new cast album on CD at all, you might ask? Musically, it’s so shortened that one cannot talk of “full” musical enjoyment. While Ernst Märzendorfer was the first in 1987 to record the original 1883 Viennese version, based on the then new critical edition (with Jeanette Scovotti, Karl Dönch, Wolfgang Brendel et al), there still is no recording of the legendary Berlin world-premiere version of 1883, which is also available as a critical edition.

Playbill for the 1883 premiere of “Eine Nacht in Venedig” at Theater an der Wien. (Photo: Theatermuseum Wien)

On YouTube you can watch a trailer for the Graz production, you’ll notice that the Duke of Urbino is presented as a Karl Lagerfeld double, surrounded by pretty female fashion models. What exactly Eine Nacht in Venedig has to do with Lagerfeld and the fashion world remains a mystery to me, but Alexander Geller seems to be a very convincing Caramello, not just acoustically (as heard on CD) but also visually. (Maybe the Lagerfeld side of things worked better for French audiences in Lyon?)

If you want to hear the irresistible “Sei mir gegrüßt, du holdes Venezia“ song in its original form, try the Simplicius recording under Franz Welser-Möst (EMI) and the title hero‘s No. 12a: “Der Frühling lacht, es singen die Vögelein.“ Korngold uand Marischka only adapted it textually, and Martin Zysset sings it impressively, live in Zurich 1999. Plus: there is no competition, because it’s a one-of-a-kind recording!

Such willingness to be unique – in terms of operetta generally and Nacht in Venedig in particular – is something I wished cpo would demonstrate too. A recording of the 1883 Berlin version would have made for a “new” and “competition free” entry into the catalogue, which the soloists from Graz would have benefited from. For the 1929 version you probably need more star quality to step into roles re-created by Jeritza, Kern, Claus, Jerger and Pataky. And you’d need a “modern” Hubert Marischka as Caramello. But finding someone with those qualities is absolutely possible if you look outside the usual opera suspects and search in the world of musical comedy and cabaret.

Sofar, cpo has not been very good at that. And neither has Oper Graz been good at it, because with such a cast they might have made even the over-familiar 1923 version “novel,” after all, back then at Theater an der Wien not a single opera singer was involved, other than Richard Tauber. As far as I know no modern recording using musical comedy people and cabaret singers has been made of the first Korngold version. And back in 1883 no opera singer was in sight, either. Taking that information as a guide line would have enabled Graz and cpo to score all the way.

But that’s something one must actually want, and spend a moment (or two) thinking about.