Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

11 January, 2025

In Braunschweig, Germany, a new production of Im weißen Rössl by stage director Immo Karaman is causing quite a bit of controversy. Critics raved about the ‘queer reading’ that shows Josepha as a man-in-drag (or trans woman) who is eventually erased from the story by the Nazis and homophobic post-war society. At the same time, visitors have sent in letters to the local newspaper claiming the production “ruined” and “distorted” the piece, saying the production was an “impertinence” and “imposition”. Other visitors wrote to say how much they loved this version.

Scene with Josepha (Matthew Peña, right) and chorus in “Im weißen Rössl”, Braunschweig 2024. (Photo: Björn Hickmann)

The staging by Mr. Karaman is not the first to turn Rössl into a (more or less) queer story or find queer elements in the story. Most recently, Philipp Moschitz in Darmstadt showed Leopold and his assistant Piccolo as lovers (played by Tobias Licht and Jendrik Sigwart), together with the White Horse Inn-proprietress Josepha they form a “throuple” in the end. In the upcoming book Glitter and be Gay: Releaded Nick Sternitzke argues that this 2024 pairing of all three as a happy threesome “probably hasn’t been seen in the operetta world before.”

The 2025 edition of “Glitter and be Gay: Releaded”. (Photo: Männerschwarm / Salzgeber)

In the same essay, Mr. Sternitzke describes a Rössl production in Bremen by Sebastian Kreyer in 2015 which starred Desirée Nick as Josepha. In that production everyone was ‘gay’ and/or cast in a gender-reverse way. Ottilie became “Otti,” a young man, while Klärchen turned into “Karlchen.” Both find the men-of-their-lives in Salzkammergut. And the emperor became an empress, looking like Sissi, to name just a few aspects of that production which made headlines mostly because of realty TV superstar Miss Nick in the lead.

Ivan Marković (l.) as Leopold and Valentin Fruntke as Piccolo in “Im weißen Rössl”, Josepha looks on from the back, Braunschweig 2024. (Photo: Björn Hickmann)

Now, in Braunschweig, Mr. Karaman choses a somewhat different path that requires a lot of prior knowledge of the show, it’s creators, and its performance history (plus the history of operetta practices in Germany/Austria throughout the ages) to be fully understandable. In the course of the performance we kind of move through different decades on stage: starting with a grey mass of people, working class, longing for an escape that the Alpine world of Rössl offers. Once the action moves to St Wolfgang the grey of the chorus moves to the side and the action becomes ‘colorful’. This might refer to the situation of the audience in 1930.

Hiding Behind a Heterosexual Appearance

Leopold is shown as an excentric actor (played by Ivan Marković) in constant exchange with a very adult Piccolo (Valentin Fruntke). Because most of their dialogue is cut, it’s tricky to understand what their relationship is supposed to be. But it seems this Leopold is in love with Josepha who enters as a perfectly costumed Alpine beauty, played by tenor Matthew Peña as a man in drag (or a trans woman?). The chorus as ‘the people’ on stage doesn’t seem to notice anythig ‘unusual,’ or doesn’t care. How much of it Leopold notices is unclear. But he woes Josepha, as the libretto demands. Making these two characters two gay men hiding behind a heterosexual outward appearance or a queer couple with a trans woman as part of the duo.

Milking the cows: the dancers in the shed in “Im weißen Rössl”, Braunschweig 2024. (Photo: Björn Hickmann)

At this point in the production, sexual liberation in general is celebrated, for example in the famous cow shed scene, where the cows (played by male ballet dancers) are ‘milked’ till they squirt. At the end of that very extended ballet sequence Josepha comes in an personally ‘tests’ the milk of the hunkiest cow, licking her cum-stained fingers and nodding in approval of the sex-party atmosphere in her back yard.

As the story moves forward, we also move forward in time to the Nazi annexation of Austria. The entrance of the emperor in act 2 is the turning point here. He’s ‘The Führer’ everyone is waiting for. A big fascist flag comes down and dominates the stage. The Aplin idyll becomes a dangerous place where, in another big ballet scene, the tourists shoot down cute little rabbits. Just because it’s fun.

Alpine scene in “Im weißen Rössl” with the ballet, Braunschweig 2024. (Photo: Björn Hickmann)

Restoring a Traditional Order

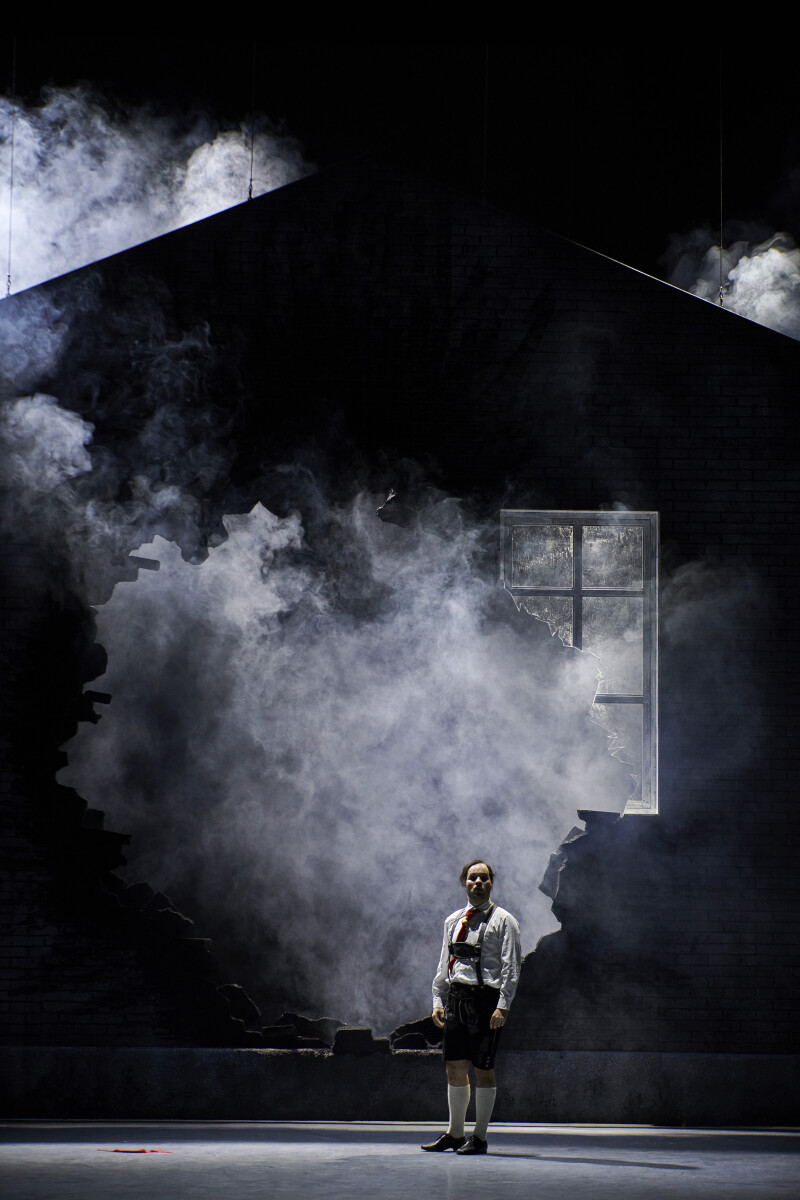

It’s clear that a new time has come that isn’t as welcoming to gay/trans people anymore. And somewhere along the way Josepha-played-by-a-man is simply pushed out of the story by Piccolo and substituted by a new Josepha played by Milda Tubelytè (who was previously seen as the yodeling Kathi). So things are ‘restored’ to a more traditional ‘order’ with spooky undertones when a bomb hits and we see the hotel wall on stage with a giant hole in it. This formerly colorful operetta paradise lies in ruins and returns to the grey of the beginning.

The ruins of “Im weißen Rössl”, Braunschweig 2024. (Photo: Björn Hickmann)

To esacpe this new bleakness, the action now espaces to a different counter-world: the tv operettas of the post-war era that many in Germany remember from the 60s and 70s, if they are old enough. On stage we see rosé-colored curtains as a pseudo tv studio where the ‘traditional’ Josepha (Tubelytè) is now the hostess of her own operetta show (like Anneliese Rothenberger used to be).

The Emperor appears in a tv studio set in “Im weißen Rössl”, Braunschweig 2024. (Photo: Björn Hickmann)

Wunschkonzert

The rest of the story is reduced to a string of ‘silly’ musical numbers for which the actors playing the Kaiser, Dr. Siedler and Ottilie, Sigismund and Klärchen, waltz in, sing, and waltz out. Plot is irrelevant, operetta is ‘Wunschkonzert,’ a string of happy melodies for the masses. In this world there is not room for the ‘original’ Josepha (Peña) now in conventional male attire and his/her lover Leopold (Marković). Both are outcasts now. And we see them, at the end, standing at a deserted bus stop on a grey/black stage, walking off into the night … destination unknown.

“Im weißen Rössl” in Braunschweig, 2024. (Photo: Björn Hickmann)

To say this is not particularly uplifting or entertaining would be an understatement. When the curtain comes down there is no applause music in the form of a reprise of the rousing Rössl march. The audience is left with a grim ending, which makes little practical sense because so much of the dialogue has been cut (even entire characters such as Professor Hinzelmann) and because the ‘new’ story of Josepha/Leopold isn’t made very clear in itself. Add to that, that Mr. Peña has a great singing voice, but he’s hardly a character actor who can pull off a portrayal like the one he’s (supposefly) asked to deliver here. And Mr. Marković, though a trained actor, doesn’t have quite the acting chops needed either to make his role and his love for this kind of outsider-Josepha memorable.

Love in a Hostile World

You could say: it’s not a fun experience watching this Rössl. Neither in the musical numbers as conducted by Alexander Sina Binder (more Wagnerian and expansive than Benatzky appropriate and snappy) nor in the dance sequences, which are choreographed by Fabian Posca in a routine fashion without any noteworthy special twists.

So I can understand some of the enraged letters of visitors to the local newspaper. Mr. Karaman’s idea is nonetheless interesting, fascinating even. But the execution doesn’t really work, for me, since the ‘new’ story Mr. Karaman wants to tell – or rather the formerly ‘hidden’ story – doesn’t come across in a convincing way as executed here with these soloists and in this radically abridged version (dramaturgy: Sarah Grahneis).

Yet, with all that said, I am glad I went to see it. Because some scenes have deeply imprinted themselves in my memory, not so much the cow shed moments, but rather seeing Josepha alone and isolated, cast out by society, searching for her place and for love in a hostile world.

The dance company in “Im weißen Rössl”, Braunschweig 2024. (Photo: Björn Hickmann)

The art of operetta would have been to show this without losing your humor and jumping off into the deep end of tragedy instead, without resurfacing.

The production runs in Braunschweig till March, it is an interesting alternative to the new Im weißen Rössl at Volksoper Wien which deconstructs/updates the piece in yet another way that is not nearly as groundbreaking as Mr. Karaman’s approach. And certainly not as queer.