Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

24 December, 2022

When the Komische Oper opened its doors on 23 December 1947 – in the Soviet controlled section of Berlin – it marked the start of a new era. The first production was Walter Felsenstein’s version of Die Fledermaus. Now, the company celebrated 75 years of setting operetta (and opera) standards with a big gala.

The finale of the jubilee gala at Komische Oper Berlin. (Photo: Barbara Braun)

When Walter Felsenstein was appointed new artistic director of the hurriedly rebuild former Metropoltheater in Behrenstraße, the Russians in charge of cultural life in East-Berlin wanted a clear cut. During Nazi times the house had been the most prominent venue for operettas created in the spirit of fascism. Heinz Henschke as director produced and co-wrote works like Maske in Blau and Hochzeitsnacht im Paradies. Works that offered escapism and hidden ideology. Works that were now shunned in the East as “contaminated”. (The situation was very different in the West.)

By renaming the theater “Komische Oper” and by putting Mr. Felsenstein in charge, the East-Berlin military government opted for a “revolution”, as Frank-Walter Steinmeier pointed out in his speech at the 75th birthday gala: Before, singers where little more than “puppets” on stage, the German president Steinmeier said, “standing around and presenting music”. But Felsenstein wanted them to act and “create believable human characters”. It was the moment when modern-day “Regietheater” was born.

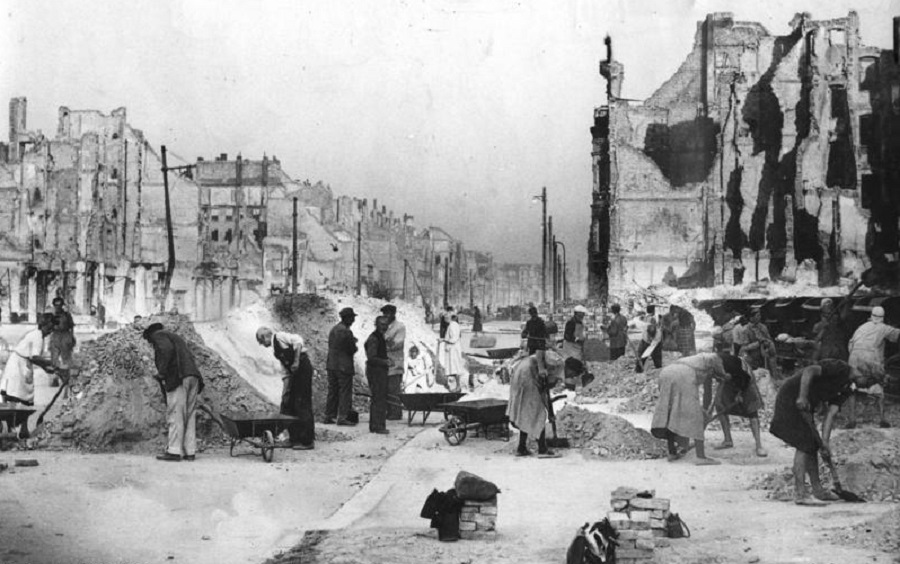

Felsenstein had made a splash a little earlier with a production of Offenbach’s Pariser Leben at Hebbel Theater in West-Berlin. He was Austrian, had been brought to Berlin during the war years by Heinrich George who was intendant of the Schiller Theater. Felsenstein managed to get the Soviets to approve the rebuilding of the bombed out theater in Behrenstraße. Only the auditorium had survived, plus the pompous staircase. The rest, i.e. the entire theater around the auditorium, had to be reconstructed with simple means, since there was a shortage of everything amid the general ruins of Berlin.

Cleaning up work at Frankfurter Allee in East-Berlin after the war. (Photo: Bundesarchiv)

Now, for the big gala event, Komische Oper started their jubilee concert with the overture of Fledermaus, conducted by Hendrik Vestmann. Axel Ranisch – in charge of the scenic realization – had to brilliant idea to balance the music with a film montage that shows what Berlin and Komische Oper looked like in 1947. The clash of audio and visuals was striking. Because the carefree spirit of Strauss’ music is a maximum contrast to what the people of Berlin had to live through at the time. Which is probably why they flocked to see a show like Fledermaus in a version that didn’t just wallow in pretty music (like the New Year’s Concerts from Vienna do today), but took the story and the characters seriously. Making them interesting and relatable. And liberating operetta from the (not so) subtle indoctrination of Nazi times. But also liberating it from the way it was presented in the West of Germany as a pain killer: with no references to current politics, the past, sex, diversity, or anything that might “disturb” the calm of traumatized post-war Germans.

The Komische Oper in 1956. (Photo: Bundesarchiv)

The Soviets might have given operetta (and opera) a new “serious” start at Komische Oper. But they also continued the Metropoltheater tradition, the former Admiralspalast around the corner from Komische Oper was chosen as the new venue for “lighter entertainment”. There, operettas were shown on a much more regular basis than at Komische Oper. But there, too, a political message of “socialist realism” was enforced and the repertoire checked for political relevance. (For more information on operetta under socialism and communism, click here.)

A scene from the jubilee gala with images of “Schlaues Füchslein” in the background. (Photo: Babara Braun)

Felsenstein created a “Typentheater”, as Frank-Walter Steinmeier said in his gala speech. A theater in which characters and types dominated, not interchangeable actors. Felsenstein turned the productions at Komische Oper into a “calling card for the new German culture,” Steinmeiner said. Many travelled internationally and were toasted all over the world.

One of the most famous of these travelling productions was Felsenstein’s version of Offenbach’s Ritter Blaubart, his greatest success in the 1960s and remaining in the company’s repertoire till the 90s. There’s a film version available on DVD that preserves the glory of that singular Offenbach interpretation.

The Felsenstein production of “Ritter Blaubart”, 1963. (Photo: Abraham Pisarek from the book “Theater in Berlin nach 1945: Musiktheater” / Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin)

At the gala, Axel Ranisch presented a fascinating montage of film clips showing Felsenstein at work with Anny Schlemm (his Boulotte), with the chorus, explaining to them all how to handle every nuance of the text for maximum effect. When Susan Zarrabi came out as a modern-day Boulotte in the famous Schlemm costume – accompanied by ladies of the chorus – you realized what has been lost: the attention to linguistic detail. Which is something that doesn’t apply only to Zarrabi but everyone who sings at Komische Oper today (with two notable exceptions that were also part of the gala concert).

None of the current ensemble members singing in German – as was the standard at Komische Oper until recently – works with “text” like the old East-German ensemble did. Anyone who has attended performances at the company before the fall of the wall in 1989 (or shortly after) knows what glories such textual precision can create – because the characters come alive in a different way when every word sung and said has meaning.

In the film clips, projected onto the stage behind the singers, we see scenes from Blaubart, we hear people talk about the way Felsenstein rehearsed a particular “walk” of the chorus ladies and Boulotte to get is absolutely right. And then we see today’s singers do that walk without the high precision. The contrast is almost as shocking as hearing the Fledermaus overture and seeing Berlin in 1947.

At the gala, homage was paid to the later directors of Komische Oper, most notably Harry Kupfer, Christine Mielitz as stage director, Andreas Homoki, and of course Barrie Kosky. While they all did operetta, at some point or other, it was Mr. Kosky who showed the world what the genre can be today – with his queer operetta revolution. And when Dagmar Manzel stepped out of an Egyptian sarcophagus at the end of the gala, in full Cleopatra costume, and sang her entrance song from Oscar Straus’ Die Perlen der Cleopatra, the effect almost blew away everything that had come befor.

Because Miss Manzel – just like Max Hopp, who presented his memorable Tevje from Fiddler on the Roof – has the stage presence and way of handling text that makes every second of her singing and acting a stand-out experience. Just like Felsenstein had Anny Schlemm as a muse, Mr. Kosky has been blessed with Miss Manzel as a singular translator of his scenic ideas. Because even the best ideas need someone who can turn them into stage reality. (There are various operetta productions at Komische Oper without Manzel that demonstrate what happens when there’s no one around to execute glorious concepts: they fall flat on their face.)

Sieh dir diesen Beitrag auf Instagram an

Ein Beitrag geteilt von Komische Oper Berlin (@komischeoperberlin)

The two new directors of the company, Susanne Moser and Philip Bröking, came on stage too and gave talks that sadly paled into comparison to the way Mr. Kosky entertained his audiences with speeches over the past ten years as intendant. Moser and Bröking emphasized, again and again, that Mr. Kosky will continue to work at Komische Oper, even though he’s stepped down as artistic director. But if anything, the gala and its historic panorama has shown that one cannot hold on to the past, that re-invention is necessary, that new impulses are always needed.

Max Hopp recited letters by Walter Felsenstein, outlining his vision of a new musical theater. Photo; Barabara Braun)

Is the young opera director and film maker Axel Ranisch such a new impulse for the future? He will direct a Händel oratorio this season, and there are rumors that he’ll stage his first operetta next season when the company leaves the theater in Behrenstraße, because the house needs to be renovated and a new (office) building will be added on an empty spot that World War 2 left vacant.

Mr. Ranisch would certainly carry on Mr. Kosky’s queer tradition(s). But he’s also a totally different sort of stage director, with a very different style. So, we’ll have to wait and see what happens.

At the after-party in the darkly mirrored foyer – which will be re-build in the way it used to look in DDR times, since the Berlin senate has declared it a “monument” that may not be changed – further speeches were delivered. Mr. Kosky was there, Miss Manzel, Mr. Ranisch et al too. There was free cake and champagne for everyone. And the final music of the gala was the famous Strauss’ ensemble “Im Feuerstrom der Reben”.

Let’s see what that “Feuerstrom” will bring in the future. Mr. Kosky is set to direct Lustige Witwe and Fledermaus outside of Berlin, possibly carrying the revolution he kicked off into the world. (Is that possible with such over familiar pieces and with standard opera casts?)

Dagmar Manzel as Cleopatra, surrounded by the chorus and dancers of the Komische Oper Berlin, in “Die Perlen der Cleopatra.” (Photo: Iko Freese/drama-berlin.de)

Meanwhile, The Drama Review (TDR) is preparing a special issue that Cambridge University Press will publish in 2023. It’s dedicated to the developments in German theater between 2010 and 2020, David Savran and Matt Cornish are the editors. In that volume there’s a big essay outlining what the Kosky operetta revolution was all about, and how it inspired stagings like Alles Schwindel at Gorki Theater, Frau Luna at Tipi, but also the Geschwister Pfister operetta series at Komische Oper (Clivia, Roxy und ihr Wunderteam etc.). Not to mention the work of the queer operetta collective tutti d*amore who recently presented a queerfeminist reading of Schöne Galathée and Lincke’s Lysistrata. And not to forget the successful Operette für zwei schwule Tenöre at BKA, written by Florian Ludewig and Johannes Kram. Mr. Kram and one of the two “tenors”, Felix Heller were at the gala too. Their show will return to the stage in Berlin and Trier next year. More venues are being discussed right now.

You could say: it’s a pretty “big bang” that Komische Oper and Mr. Kosky created. That’s also the title of the TDR essay, “Big Bang Theory”.

… in the above article(I don’t care to read it all because of the theme it is about) I happen to have noticed these few words ” WHAT THE GENRE CAN BE TODAY ” – and this is the indication of what I do not agree – the Komische Oper is in fact something aiming to destroy what is beautiful as it ” was ” they do love their bewildering stinking surprises – they are happy to offer them…. the operettas they think to perform have only one single respect – what? but the title … Povero teatro in che mani sei mai caduto: