Susanne Korbel

Operetta Research Center

4 August, 2016

The White Horse Inn at the Central Park – an Austrian operetta staged in New York in the 1940s? Yes, in 1941 and 1947 this happened in a migrant café not far from Central Park. The original operetta version tells a multi-layered love story before the backdrop of the Austrian Alps in summer, during the so called “Sommerfrische,” i.e. the traditional summer holidays of the bourgeoisie in the Habsburg monarchy. The central narrative of Josepha Voglhuber (the proprietress of the hotel) and Leopold (her head waiter) has been preserved in the New York adaptations. However, the two versions performed at Central Park were culturally “translated” between different traditions, and between different socio-cultural as well as -political contexts. A glance at the textbooks shows that the translation of gender specific moments of the female lead are especially interesting.[i]

Vilma Kuerer als shown in the newspaper “Aufbau” in 1941. (Photo: Susanne Korbel)

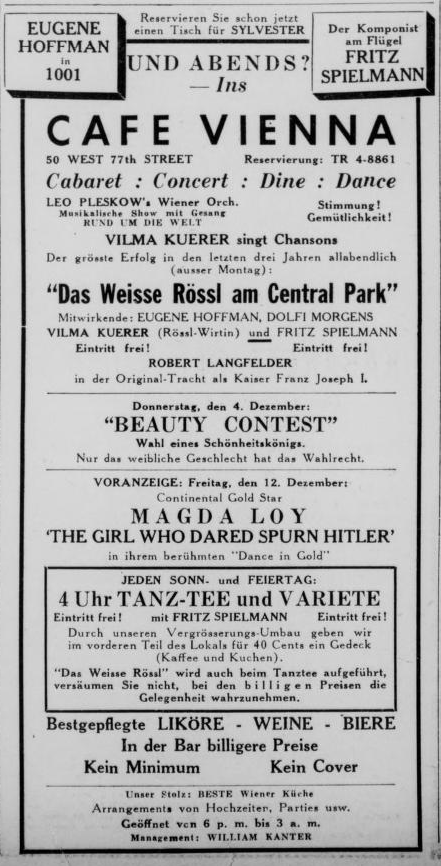

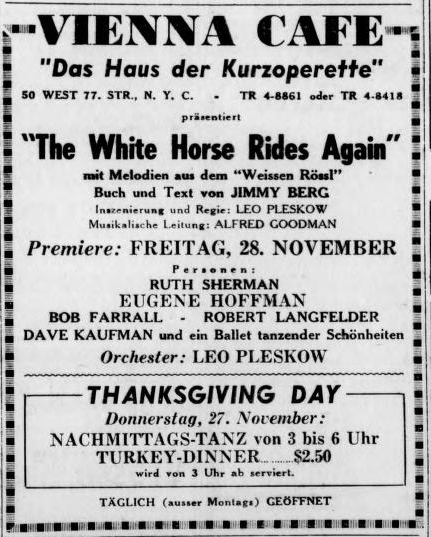

In the last days of November 1941, Vilma Kuerer performed “the Roesselwirtin at Central Park” and cast her spell on the audience of the Café Vienna. It was located on the corner of 77th Street West.[ii] Six years later, in 1947, it was Ruth Sherman who performed the “owner of the White Horse Inn.”[iii] Both versions were written by Jimmy Berg,[iv] both versions were adapted from the original Benatzky/Charell operetta of 1930, premiered at the Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin with Camilla Spira and Max Hansen as Josepha and Leopold. However, the socio-political context – influenced by politics of the Nazi regime as well as gender–based ideas of the time – influenced the variations made by Berg between his own version 1 and 2. Especially the character of the Roesselwirtin was strongly re-conceived between 1941 and 1947.[v] The character was given a new inventory of characteristics, so she could interact with her stage colleagues in a novel way, as well as with the audience which had also changed in the meantime.[vi]

The cast of the 1941 “White Horse Inn at the Central Park” with Robert Langfelder as Franz Joseph in “Originaltracht” and Vilma Kuerer as the hotel owner. (Photo: Susanne Korbel)

The two Berg versions are not a simple re-staging of the original operetta, which had been successfully performed on Broadway in 1936, directed by Erik Charell himself and starring Kitty Carlisle and William Gaxton. It was an expansive production with a cast of 162 at the huge Center Theater on Sixth Avenue. The two new versions of this ever-popular piece emerged through cultural translation.[vii] Jimmy Berg conceived both versions as Kurzoperetten (short operettas)[viii]that aimed to be played more than once every evening. In Das weisse Roessel am Centralpark (1941) and The White Horse Rides Again (1947) Berg reduced the cast and storyline, utilizing “popular Viennese melodies, mainly from ‘The White Horse Inn.’”[ix] This article will focus on the Roesselwirtin and how her role changed in the cultural translations. The analysis is based on the manuscripts of the shows and reviews of the productions.[x]

Austria, how did you change?

On Friday, November 21, 1941, Das weisse Roessl am Centralpark premiered at the Café Vienna on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.[xi] The Roesselwirtin – i.e. the female lead character – was strongly based on previous productions. Vilma Kuerer,[xii] who had to emigrate due to persecution by the Nazis, acted the part of the hotel proprietress every evening from November 1941 through February 1942.[xiii] Being dressed in garbs, the Roesselwirtin and Leopold, the head waiter, sang the original title melody of the Benatzky/Charell operetta, “Im weißen Rössl am Wolfgangsee” [At the White Horse Inn on Lake Wolfgang].[xiv]

This idyllic reference was already counteracted in the next dialog, when the Roesselwirtin entered the stage saying:

“Austria you look so strange / Austria how did you change […] Ich pack ein die Dirndlsachen / Nimm die Lederhosen rasch, / Sag zum Abschied leise Servus / Weil ich nach New York Dich lock“. [I wrap up my garbs / quickly take the leather pants / [traditional clothing in Austria] / Quietly say goodbye to the farewell / Because I tempt you to New York]

She concluded the scene, which was accompanied by the well-known melody of “Hueaho alter Schimmel, hueaho” with: “So let’s go!”

The mixing of English and German is typical for the adaption of popular pieces. The overlapping of languages can be interpreted as reflective confrontation with various kinds of dislocations (e.g. not only dislocations in physical places, but also in political or gender identity, as well as dislocation in language and/or economy). This negotiation of the dislocations, which were caused by migration and for which the performances provided a space, is a constitutive element of cultural translations.[xv]

What is more, the adaption of a character such as Josepha Voglhuber is part of these negotiations: soon after the arrival in New York, the former landlady of the hotel in Salzkammergut turned into a bustling businesswoman who was pretty uninhibited deploying her female charms. This included playing the vamp, when necessary, in order “to make a living.“ At Central Park, the newly conceived Roesselwirtin dallied not solely with Leopold, but also – as is stated in a note in the manuscript – with the editor of the newspaper Aufbau, which was the newspaper of the German-Jewish Club New York. (It seems the newspaper editor takes the role of Dr. Siedler from the original version, or Donald Hutton in the Broadway version.)

Advertisment for the 1941 production of “Das weiße Rössl am Central Park” in “Aufbau.” (Photo: Susanne Korbel)

Although the scene was created so that the intentionally male-connoted part started the liaison, the Roesselwirtin has also been thought to be capable of doing her business and to turn the tide in this tête-à-tête. She herself decided to defer to the flirt with the editor to get additional “inches” for free. She states:

„Ich hab nur geblufft / Tat es fuer’s Geschaeft / Ich war nett zum Redakteur / Und gleich gab er mir drei Inches mehr.“ [I just bluffed / did it for the business / I was nice to the editor / and he gave me immediately three inches more]

Another aspect of the character was her obsessive behavior. The staging could be described as being smartly adapted in language in a modern way. While Leopold held on to the “old” language, this interpretation portrayed the female part as the one who better adapts to the new situation:

„You can see very clearly / I must take more than I can, / But in spite of all I love him dearly – / He is my man. / So I tell him – Oh Darling, / Give me now a little kiss, / But he doesn’t get my Oxford English, / That’s how it is …“

In 1941, the Roesselwirtin ultimately stayed by Leopold’s side and clearly stated that, as a loving woman, she would always kiss him in Walzertakt, i.e. in waltz time.

The “Dark Horse Inn”

Almost exactly six years later, in 1947[xvi], The White Horse Rides Again premiered at the (renamed) Vienna Café.[xvii] In the meantime, the Roesselwiritn had became “the owner of the ‘Dark Horse Inn‘“ in the Catskill Mountains, in the Southeast of the State of NY. And she was now named Violet Brown. The part was played by Ruth Sherman, an American opera singer.[xviii] Leopold became Mr. Hinterhuber. He was the only person who performed in German, and, moreover, the only person Violet spoke German with.

Advertisment for the 1947 production “The White Horse Inn Rides Again.” (Photo: Susanne Korbel)

As in the original 1930 operetta narrative, his heart beats for Violet, the Roesselwirtin. She, however, ignores him in the 1947 adaptation. This time, several men – hotel guests, but also singers – pursue her aggressively. She declares:

„I don’t care for wolves, no siree, [!] So please take it easy with me, / I’m no fool, / I have my rule, / You see. / Don’t go too far, my friend, until we marry / My proposition is cash and carry“.

This was a reference to a movie called Forever Amber. It is a film about women who move up the social ladder with the aid of sex.[xix] As the “owner of the Dark Horse Inn“ – which became the White Horse Inn again in the last scene – she did not pursue this topic, but she emphasized: “If you can’t wait, my friend, then make it snappy, / Just get a preacher, and we’ll be happy.”

In this adaptation, sexual attributions became most evident in a scene between Violet and the “nervous guest,” Mr. Meier. The guest, who stays in the Catskills to recover his jangled nerves, turns into a very promising lover:

Mei[er]: In my arms / You’ll fell my secret charms / And you’ll discover / A true lover.

Vio[let]: What surprise / You are, I realize, / A lady killer in disguise…

Mei: It would be wonderful, my dear / To be your Casanova, / The time is now, the place is here, / So kindly think it over.

Vio: You are so tender and so gentle, / So sweet and continental, / But still to fall for your kind / Does remind me that love is blind.

Whereas in 1941 the original narrative of the operetta – the happy ending of the love story between Josepha and Leopold – was preserved, the love for Mr. Hinterhuber ends unrequited in 1947: Violet Brown eventually decides to start a relationship with an American singer.

The Emperor Scene: Kitty Carlisle and William Gaxton in the Broadway production of “White Horse Inn.”

In the 1940s, the hotel proprietress had the aura of a jazzy “man-devouring” singer of the 1920s and 1930s. Despite seemingly superficial narratives, the two versions by Berg offered an incredible range of negotiations of sexual and cultural identities. Even if it was tried to promote the performances with an accompaniment of a „ballet of dancing beauties“ and seemingly trashy romantic to make it into a money spinner,[xx] the versions played with a deviation of clichés. Violet contradicted supposedly female stereotypes, was the “owner” of a hotel she managed successfully, and staged herself confidently with a view to public appeal in a “performance.”

It would seem that the female part could be easier adapted – culturally translated – into a “vamp,” than changing the waiter into a “modern American.” This became apparent in the renaming of the characters: Leopold turns into Mr. Hinterhuber, and the Roesselwirtin into Violet Brown, with the addition “owner of the ‘Dark Horse Inn.’” Eventually, this contrast completed the parts and the narrative.

Ernst Stern’s fantasy costumes for the girl dancers in the Broadway production of “White Horse Inn.”

Both scripts for these White Horse Inn adaptations by Jimmy Berg await a modern re-examination and staging. Perhaps in New York at the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene where the Yiddish operetta The Golden Bride was recently successfully produced?

[i] To begin with, I would like to thank Joachim Schlör, who made me aware of the topic in his seminar at the Center for Jewish Studies (University of Graz). And I would like to thank Carolin Stahrenberg and Nils Grosch, who organized a symposium, that aimed at highlighting new perspectives on Im weißen Rößl, and offered me the opportuinity to present a paper on the two versions of Jimmy Berg. The volume with the papers is currently about to be published. Grosch Nils/Stahrenberg Carolin (ed.), Im weißen Rößl: Kulturgeschichtliche Perspektiven. (Populäre Kultur und Musik 18) Münster, London, New York 2016.

[ii] Aufbau, 12.12.1941 (Vol. 7, No. 50), 10.

[iii] Aufbau, 28.11.1947 (Vol. 13, No. 9), 19.

[iv] Jimmy Berg was born Symson Weinberg in Kolomyia (Galicia) in 1909. Jimmy’s father, who worked for a wine company, moved his family to a suburb of Vienna. Jimmy later worked in Berlin, Paris, Vienna and New York. In 1931, he started work as a translator of American popular songs for huge companies in Berlin and began to write his own songs soon afterwards. Because of the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, he was forced to emigrate to Paris and returned to Vienna in 1934. He finally left Austria in 1938 due to racial (as a Jew) and political persecution (as a member of the Viennese cabaret group ABC (Brettln am Alsergrund)). He travelled to New York via Zurich and London and started work as musician and composer. In 1942 he married Gertrude Hammerschlag (Trude Berg), who since then performed together with him. Horst Jarka edited Jimmy Bergs Chansons and an exhibition in the Austrian Exile Library in the Literaturhaus in Vienna, focusing on cabaret in Exile, dealt with Jimmy Bergs plays. Jarka, Horst (ed.), Jimmy Berg. Von der Ringstraße zur 72nd Street. Jimmy Bergs Chansons aus dem Wien der dreißiger Jahre und dem New Yorker Exil. New York, Washington e.a. 1996. Klösch Christian / Thumser Regina (ed.), „From Vienna“. Exilkabarett in New York 1938 bis 1950, Wien 2002.

[v] In the Postcolonial Turn in Cultural Studies, the importance of „in-between-spaces“ was highlighted. Because, as Homi K. Bhabha states, „[t]hese ‚in-between‘ spaces provide the terrain for elaborating strategies of selfhood – singular or communal – that initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself.“ Bhabha Homi K., The Location of Culture. London, New York 2004.

[vi] For the concept of “performative utterance,” see Fischer-Lichte Erika, Performativität. Eine Einführung. Bielefeld 22012. Or Bachmann–Medick Doris, Cultural turns. Neuorientierungen in den Kulturwissenschaften. Hamburg 62014: 104–143.

[vii] Another new Perspective in Cultural Studies was brought up in the Translational Turn. Italiano Frederico/Rössner Michael (ed.), Translatio/n. Narration, Media and the Staging of Differences. Bielefeld 2012. As well as Bachmann-Medick Doris, Cultural turns. Neuorientierungen in den Kulturwissenschaften. Hamburg 62014: 239–284.

[viii] The genre short operetta, musical short story oder Kurzoperette combines aspects of operetta and cabaret. The bars and cafés near Central Park were primary venues for plays belonging to this genre. Ingrid Maaß, Repertoire der deutschsprachigen Exilbühnen 1933-1945 (Hamburg: Hamburger Arbeitsstelle für Deutsche Exilliteratur, 2000), 99.

[ix] The covers of both manuscripts refer to the operetta Im weißen Rössl / The White Horse Inn. Berg Jimmy (1941), „Das weisse Roessel am Centralpark“, N1.EB-16/1.1.16, Austrian Archive for Exile Studies. [German] Berg Jimmy (1947), „The White Horse Rides Again“, N1.EB-16/1.1.15, Austrian Archive for Exile Studies.

[x] The textbooks of the Berg versions are part of Jimmy Bergs estate, which is stored at the Austrian Exile Library. Jimmy Berg, Das weisse Roessel am Centralpark, N1.EB16/2.1.2, Nachlass Jimmy Berg, Exilbibliothek Österreich. Jimmy Berg, The White Horse Rides Again, N1.EB16/1.1.15, Nachlass Jimmy Berg, Exilbibliothek Österreich.

[xi] Aufbau 46, November 14, 1941, 8.

[xii] Vilma Kuerer worked for the US war intelligence OSS as „Propagandastimme“ [voice of propaganda]. Florian Traussnig, Geistiger Widerstand von außen: Österreicher im US-Propagandainstitutionen im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Wien, Köln, Weimar 2016 [in print].

[xiii] Susanne Korbel, Das weisse Roessel am Central Park. Jimmy Bergs Kurzoperette „in schlechtem Deutsch und ebensolchem Englisch“, in: Grosch Nils/Stahrenberg Carolin (Hrsg.), Im weißen Rößl. Kulturgeschichtliche Perspektiven. (Populäre Kultur und Musik 18) Münster, New York 2016: 215–234.

[xiv] Aufbau, 5.12.1941 (Vol. 7, No. 49), 14.

[xv] Joachim Schlör highlighted, that performances, plays, songs etc. were third spaces (in-between spaces) themselves. Joachim Schlör, Werner Richard Heymann in Hollywood: a case study of German-Jewish emigration after 1933 as a transnational experience, Jewish Culture and History, 2016, 1. Klaus Hödl emphasized that popular culture served an important space for Jewish and non-Jewish relations. Klaus Hödl, The quest for amusement: Jewish leisure activities in Vienna circa 1900. in: Jewish Culture and History, 2013 (14/1), 1-17.

[xvi] Aufbau 48, November 28, 1947, 19.

[xvii] After a new management reopened the café on April 8, 1944, it was named the Vienna Café instead of Café Vienna. Aufbau 14, April 7, 1944, 13.

[xviii] Aufbau, 19.12.1947 (Vol.13, No. 51), 19.

[xix] „Forever Amber“, playing in 17th century England, was written by Kathleen Winsor and appeared in New York in 1944. In 1947 it was made into a film.

[xx] See advertisements.