Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

14 October, 2016

Here is a new and first complete recording of Nico Dostal’s 1939 operetta Ungarische Hochzeit – premiered at the opera house of Stuttgart, Germany, shortly before the Nazis unleashed World War II by invading Poland as their Hinterland and Lebensraum. The operetta tells the story of a group of settlers (“Kolonialisten”) sent out into the world, back in the 1750s, to populate new territories and marry “racy” attractive young women, promised to them by the government as a special “prize”, together with free land if they venture East.

Dostal’s copy of “Gräfin Mariza”: the ultra-Hungarian “Ungarische Hochzeit”.

Of course, this being a “big sing” opera-operetta from Nazi times, the whole business of colonizing the world and forcing foreign women into marriage with tricks and disguises is presented as a “comedy,” costumed as a “good old times” Hungarian tale of lusty men (and women) and spiced with “Hungarian” flavored music in the style of Strauss’s Gypsy Baron and Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies. You would need to be blind not to see the ideological implications of this operetta based on a libretto by Hermann Hermecke, and you’d have to be truly naïve to suggest – as booklet author Alexander Dick does in this cpo release – that this “late and last great silver age operetta” is “deserving of more attention once more.” Is it because we are living in times in which Time magazine has an October 2016 cover story headlined “The New Faces of The Right: A Resurgence of Nationalism Has Forced European Politics to Tilt Sharply”? No, Mr. Dick’s explanation as to why one should pay more attention to Ungarische Hochzeit again is solely based on his appraisal of the “artful and clean” (“kunstgerecht und sauber”) way the Dostal score is composed, even though Dick admits that the libretto by Hermecke is borderline questionable.

Of course this is an old argument, claiming “the music” is so beautiful that you can forget about the idiotic lyrics and dialogue.

While this might be true in some instances, most operettas of relevance and international fame have had snappy and memorable lyrics that take a very contemporary look at the world even when the stories are set in distant times. (This is true also for Hungarian themed operettas: from Strauss’s Zigeunerbaron 1885 to Kalman’s Der Teufelsreiter 1932.) The text book and lyrics in Ungarische Hochzeit are, by contrast, a painful reminder of what happened to German language operetta after the forced exit of 90 percent of the (Jewish) authors: all originality, self-parody and wit has disappeared, replaced by an endless rehash of worn-out clichés and phrases, in this case mostly circling around key words like “paprika” and “goulash”.

As far as the music goes, there is one hit number familiar to most operetta lovers today as a soprano favorite: “Spiel mir das Lied von Lieb und Treu.” Sung here by Dostal’s wife Lillie Claus.

It’s one of many melancholic numbers written for a legitimate opera voice, in sync with the Nazi ideal that operetta as an art form needs to be elevated to “higher regions”: which is why this Ungarische Hochzeit premiered with opera singers at the Stuttgart Opera House, directly followed by a second production at the Nuremberg Opera, instead of Kalman’s comparable Der Teufelsreiter which came out at the Theater an der Wien with specialized actors such as Hubert Marischka and some imported film superstars like Lil Dagover. Kalman, in 1932, made his historic characters dance rumba and foxtrot, unmistakably connecting the 18th century story to modern times. Dostal avoids such “degenerate” modernisms in his dance numbers (e.g. “Kleine Etelka”) and strives for a more “high class” approach, which does not do the genre a favor and is – ultimately – dreadfully boring.

So far, there has been a EMI highlight version of Ungarische Hochzeit in circulation, with Margit Schramm singing the big soprano solos under the direction of Dostal’s son Roman. (With the orchestra Philharmonia Hungarica, to make it sound more “authentic.”) There is also a 1968 TV version starring Hungarian diva Maria Tiboldi, plus Peter Minich, Ferry Gruber, Monika Dahlberg, and Maria Schell as the Empress Maria Theresia. All highly ‘serious,’ of course. Just like this alternative 1960s Viennese version, not available on CD, but preserved by YouTube.

While the EMI recording is attractively sung, it does drag on a bit because there is little contrast in the music and little bounce that would be comparable to Dostal’s earlier South-American operetta-gem Clivia (1933). Also, you hardly register the story on EMI, because there is no dialogue. On the new cpo recording, based on a production of the festival in Bad Ischl, there is a lot of dialogue delivered in typical “operetta” fashion by singers who are not actors. The results, though noticably lively and supervised by a dialogue coach, can be … testing.

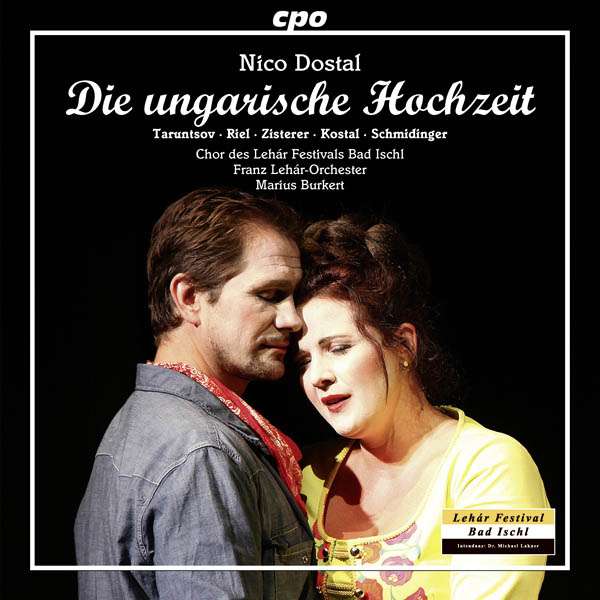

Cover for the cpo version of “Ungarische Hochzeit” from Bad Ischl.

But I have to hand it to the casting department: in contrast to earlier (disastrous) Ischl recordings, everyone here is easy to understand throughout, so you can follow the story without a full libretto, which is not included in the booklet. The mix of Austrian, German and Hungarian dialects is, mostly, refreshing.

The lead soprano role of Janka is taken by Regina Riel who got some positive reviews, for example by Benjamin Künzel on klassik.com. You could describe Riel’s singing as old-fashioned in a good way: her lyrical voice production is reminiscent of sopranos from the Nazi era, like Maria Cebotari. Which is meant as a compliment. But Riel lacks the fire of Cebotari and the glamour of her high notes. She is pleasurable enough to listen to, not sensational. But “sensational” is what this music needs if it is to be remembered at all. And Riel’s big solo does not ooze sentimentality and warmth to make it a serious competition to the likes of Lucia Popp who made “Spiel mir das Lied von Lieb und Treu” an absolute showstopper.

The tenor Jevgenij Taruntsov as the disguised Count Stefan Bárdossy (who dresses up as his man-servant and falls in love with Janka who, in turn, is a noble man’s daughter but disguises herself as a maid) looks dashing on the photos, but sounds labored most of the time, certainly in the higher regions of the role, which doesn’t help make the big love scenes sparkle.

I found the way soubrette Anna-Sophia Kostal handles the silly jokes of Etelka rather entertaining, and I certainly enjoyed the out-and-out farcical way Dolores Schmidinger played the Empress Maria Theresia in the last act. It’s a total contrast to the way Maria Schell did it. And it’s the only time, here, that anyone dares to demonstrate the silliness of the dialogue full on and unashamedly, making it fun to listen to.

A historical map showing how the Nazis “found” new “Lebensraum” in the East.

However, the elements don’t fit together. Conductor Marius Burkert tries to creat a certain magic in the up-tempo dance numbers (which include remains of a once “modern” orchestration), but for the most part he has no idea how to turn this 1939 score into an overall convincing sonic experience that balances the various musical elements: czardas, Spieloper choruses, languorous love duets, bouncy peasant numbers, melodramatic climaxes, and arty instrumental solos. It all sounds more or less the same here, there is no acoustic dramaturgy and no deeply felt energy in the orchestral playing.

Which leaves me wondering: why would anyone want to have this recording?

As a document of operetta history, after it had been substantially re-defined and re-written by the Nazis, this is obviously an interesting show worth knowing and examining carefully. But this production – as seen, too, on the pictures in the booklet – pays no tribute to the problematic historical background. It’s exactly the good-old-times-saga the Nazis intended it to be, brainwashing listeners without them noticing. At least that was the idea back then, and it still seems to work today. Mr. Künzel on klassik.com even writes: “In contrast to the questionable entertainment products of Fred Raymond or Friedrich Schröder, Nico Dostal’s musical theater does not leave an unpleasant aftertaste that reminds you of the music industry of the Third Reich” (“Im Gegensatz zur fragwürdigen Unterhaltungsware eines Fred Raymond oder Friedrich Schröder hat NicoDostals Musiktheater keinen unangenehmen Beigeschmack, der an die Musikindustrie des Dritten Reichs denken lässt”). It seems a younger generation of critics does not want to see what is staring them right in the eyes; Mr. Künzel is only of of many young operetta specialists who this can apply to.

Compared with other “late” big sing operettas, most notably Lehár’s 1934 Giuditta (also premiered with opera singers at an opera house, in that case Tauber/Novotna at the Vienna Staatsoper), the tunes in Ungarische Hochzeit cannot stand up. And this new cpo release cannot compare with cpo’s quite convincing Giuditta which we reviewed positively not too long ago.

If your German is not up to it, and you won’t be able to follow the earth shattering dialogue, then stick to the old EMI version with Dostal Jr. conducting. The overall singing from Ischl is not luxurious enough to replace Margit Schramm, Anton de Ridder and Willi Brokmeier. If you want to experience the full story of these “colonialists” and the way they “grab” women as their prize, to populate new provinces for their government in annexed lands, then you will need to stick to this cpo version for the full effect. By the way, there are no “gypsies” in this show, because by 1939 the Nazis had already begun deporting them, on a grand scale, to concentration camps.

The Nazi establishment of German “Lebensraum” required the expulsion of the Poles from Poland, such as in Reichsgau Wartheland, 1939.

PS: I find it downright scandalous that Alexander Dick in his booklet essay ignores all of these historical backgrounds, instead claiming that “stylistically” this operetta sounds as if it had been written at the same time as Csardasfürstin, i.e. during World War 1, before the 1920s jazz revolution advocated by Kalman, Granichstaedten, Charell, Haller or Abraham. Which for Dick seems to be a very positive thing. That this musical role-back of the genre was exactly what the Nazis wanted is not mentioned, not even in a footnote. He does mention the missing gypsies, as a sole hint of political realities in 1939. But mostly he urges us to pay attention, once more, to Ungarische Hochzeit. Because this is “a late and last masterwork of a grand silver operetta tradition started by Lehár and Die lustige Witwe.” I must confess: if such renewed attention looks and sounds like this 2015 Ischl production, I can do well without it. But maybe the resurrection of ideologically “tainted” shows such as this one reflects the current political climate in Europe after all? If so, it’s frightful.