Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

4 October, 2001

Often, in earlier times, quoted as “the first landmark in the history of the American musical theatre”, the 1866 extravaganza production of Charles M Barras’s play with music by Thomas Baker and others in New York was put together on the lines of the French grand opéra-bouffe féerie and/or its German equivalent. It was long alleged to have been created by the last-minute insertion into a fairytale piece destined for Niblo’s Garden of the personnel and some of the repertoire of a stranded French ballet troupe, whose theatre had burned down.

Niblo’s Garden in New York, at the corner of Prince Street and Broadway. It was demolished in 1895.

This myth (which put itself in place soon after the events, and was subsequently repeated in variously ‘improved’ versions in the obituaries of those concerned in the making of the show) has now been itself relegated to the fairytale books, and contemporary sources tell a less circumstantial tale (in which the bones of the myth can nevertheless be discerned) about the genesis of the show and of the burning of the New York Academy of Music, where Grau’s Italian Opera company were playing on that fatal 22 May 1866. A full three months before Niblo’s even put The Black Crook into rehearsals.

It seems what really happened was this. Actor Charles Barras wrote The Black Crook as a spectacular touring vehicle for himself and his wife, dancer Sallie St Clair, and in order to equip his show with the required imprimatur of ‘a New York success’ prior to touring, he negotiated with William Wheatley, manager of Niblo’s Garden, for one hundred performances at his theatre. For Wheatley to agree to this remarkably long run, success or failure, Barras must have come up with some stinging inducement. It appears that this inducement was some kind of a sharing terms arrangement, but it is fairly obvious that Mr Barras was in effect paying for his piece to go on to establish its title for the future. The deal in place, the author set to preparing the scenery and properties for his production at the Academy of Music in his summer hometown of Buffalo, NY. At this stage, Messrs Henry Jarrett and Henry Palmer came into the picture. Having recently formed a producing partnership, they’d been over in Europe ‘looking for novelties’ to import to America. Amongst what they’d seen were a production of La Biche au bois in Paris, and the pantomime at Astley’s Theatre in London, and they had decided that they would put on a show back home which utilised some of the more original spectacularities they’d seen in those two pieces. They’d talked to some of the lead dancers from the Paris show, they’d negotiated the purchase of the big transformation scene from the London panto, and they had had the thought their as yet unwritten show might go well (and not too expensively) at the Academy of Music. But then the Academy burned down, and so the would-be-producers made their way instead to the other home of New York spectaculars, Niblo’s. But Niblo’s wasn’t available. Mr Barras had booked it for his 100 performances.

Quite whose idea it was to mix and match, and to slip the bit of British panto Jarrett and Palmer had already paid out their money for into “The Black Crook” isn’t recorded.

But the result of the negotiations that ensued among Wheatley, Jarrett, Palmer and Barras was that Barras was relieved of his potentially onerous ‘sharing’ terms and paid instead a small flat sum as a royalty, and Jarret and Palmer effectively took over as producers of the New York mounting of his play. And the first thing Jarrett did was to set off overseas again to start gathering up the ideas, decorations and personnel which they wanted to change the show from a spectacular melodrama into something more like Paris’s La Biche au bois. A veritable pot-pourri of scenery, mechanics, costume and girls. Barras’s scenic and costume designs, of course, went completely by the board. His half-made sets and clothes stayed behind in Buffalo, whilst the new producers ordered new ones more in line with the Parisian-Londonish spectacle they intended to produce. In the end, Jarrett arrived back in New York only the day before rehearsals began, bringing with him 45 dancers and actors to add to the local contingent hired by Wheatley (‘wanted 60 ballet girls for Black Crook at Niblo’s’), and many a crate of European props.

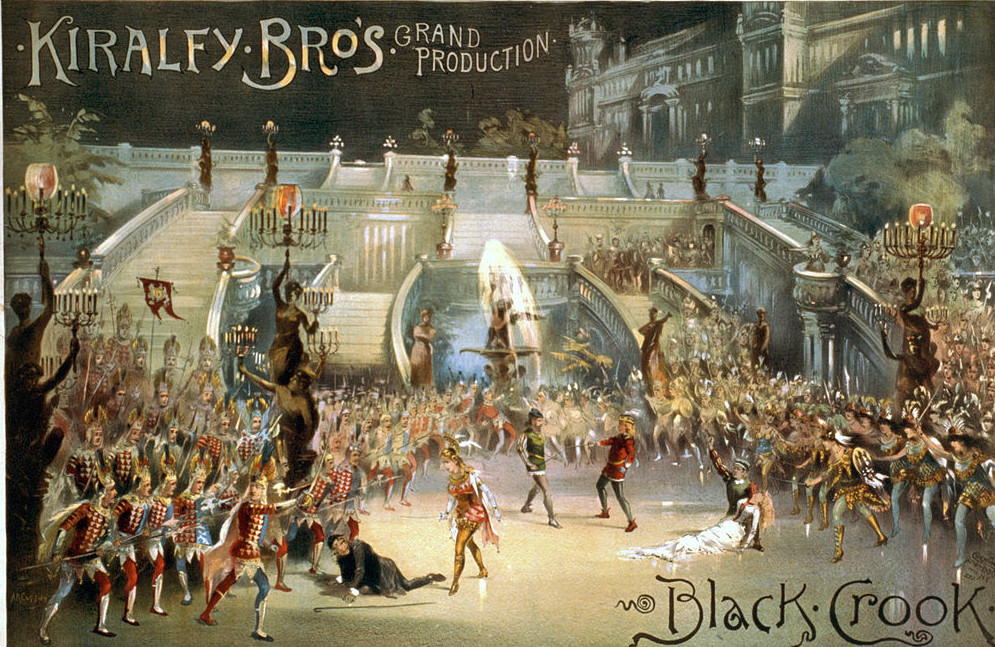

The finale of “The Black Crook” 1866.

By the time they opened, the extravaganza (‘written expressly for Mr Wheatley’) ran for a full five hours. And that in spite of the fact that great chunks of Barras’s text, including his big final climax, which had got in the road of the panto transformation, had simply and blatantly been cut out. But if there wasn’t too much constrcution left, the show now included a full score of songs and choruses by various writers, some new and some borrowed, selected and arranged by house musical director Baker, a great deal of ooh-aah mechanical scenery and a vast dose of the legshow ballets and parades typical of the more grandiose French productions, all of it mixed in with Barras’s scenes of fairytale drama and romance to make up a highly attractive if reasonably incoherent and lengthy opéra-bouffe féerie entertainment. The show’s priorities were visible from its advertising: the splendid ‘Tableaux, Costumes, Marches, Scenery’ (‘operated by 71 stage-hands’) and the ‘premium transformation’ (‘purchased entire from Astley’s Theatre, London’) were splashed large across announcements which did not even mention the text or the music, and the ‘Grand Parisienne Ballet Troupe’ (62 girls , 39 American and 23 British, but nevertheless advertised as being fashionably French) and the ‘Garde Imperiale’ of marching girls were prominently billed, whereas the names of the principal actors and singers were nowhere in sight.

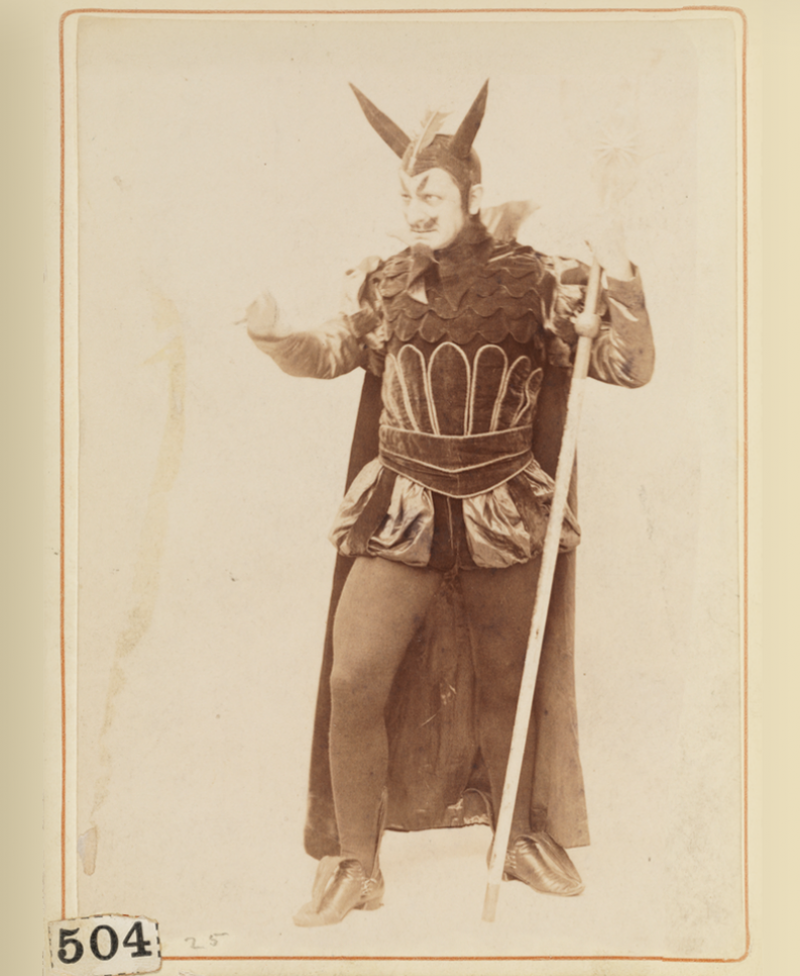

The devil in the original 1866 production of “The Black Crook.”

Barras’s tale was rather more Germanic than French, telling of the plots concocted by the vile Hertzog (C H Morton), under the spell of the diabolic Zamiel (E B Holmes), to deliver up a monthly ration of human souls to the powers below. Hertzog selects the artist, Rudolf (G C Boniface), whom he frees from the clutches of Count Wolfenstein (J W Blaisdell), as his victim of the night but, as he leads him to his fate, the young man saves the life of a benighted dove. The dove is the disguised fairy, Stalacta (Scottish opera soprano Annie Kemp Bowler), and in the course of the evening she outwits Hertzog and steers Rudolf to a happy ending with the fair Amina (Rose Morton). The comedy was provided by the dramatic folks’ servants, with J G Burnett as von Puffengruntz producing the lowest of it, and the musical hit of the show was a soubrette number ‘You Naughty, Naughty Men’ as introduced by Millie Cavendish (who died four months into the run) in an incidental rôle.

The Black Crook provided New York with its most effective piece of grosse Spektakel-Feerie to date, and – perhaps even more attention-pullingly – its most uninhibited mass view of apparently little-clad female limbs to date, and those legs and the displays of scenic machinery roused an unparalleled interest as, with an ever fluid programme of components, the show ran on on Broadway for fifteen and a half months, closing 4 January 1868 after 475 performances.

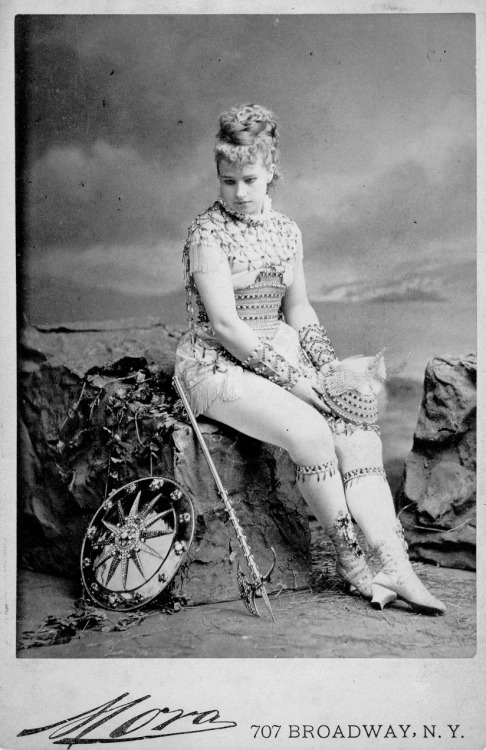

Singer and burlesque dancer Pauline Markham as Stalacta, Fairy Queen of the Golden Realm, in “The Black Crook.”

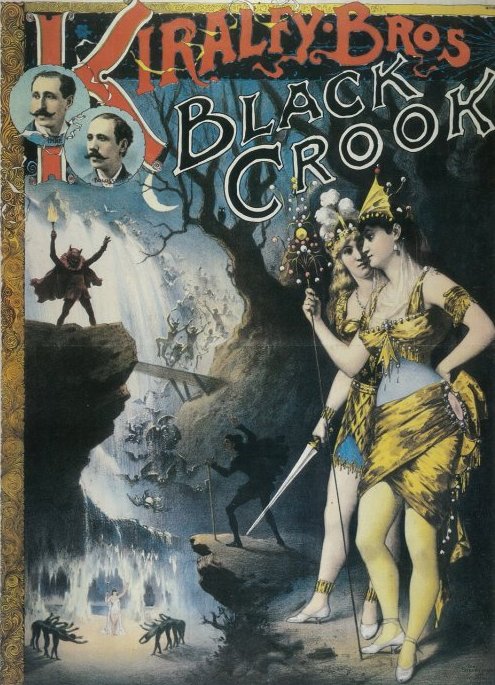

With his title more established than he could ever have dreamed, Barras quickly got his rather less grandiose production (‘without the imported nudities..’) off the mark at Buffalo, and the show was repeated thereafter, in often largely varying versions, all around the country, to the great profit of its author who had, as planned from the start, reserved to himself all outside-New York production rights. Thus, for the few years of his life that remained, he collected largely as Black Crook productions – many bearing little resemblance to his play, and merely using the title as a come-on signalling ‘legshow with scenery’ – sprung up. The show also made intermittent return visits to the New York stage over a number of years (Niblo’s Garden 1870, 123 performances, 1871, 87 performances, 1873 130 performances &c) and in latter days it was toured long around America by the country’s most determined spectacle merchants, the Kiralfy brothers.

The Black Crook Company 1893, following the European practice of using women in male roles. Photograph by Napoleon Sarony.

A sad coda to the tale. Wheatley, Jarrett and Palmer all made fortunes from the Niblo’s run of The Black Crook. The bought-out Barras had to wait till a little later to make his money. He certainly did — John McDonough snapped up the rights for a dozen major cities, John Meech of Buffalo for 16 lesser ones, and Maeder, Davey and Curran for the minor towns of 15 states – but he had little joy of it. Sallie, for whom the piece had been written, died (Buffalo, NY, 9 April 1867) even before the New York run had ended and, soon after, a depressed Barras sold his mansion at Cos Cob to Edwin Booth. Finally, on 30 March 1874, he threw himself from a moving train.

The Black Crook became, during its months as a Broadway phenomenon, the butt of burlesque in virtually every minstrel and burlesque troupe in town. Christy’s Minstrels, the San Francisco Minstrels, Kelly and Leon (The Great Black Crook Burlesque) all featured parodies of the show, Tony Pastor offered John F Poole’s The White Crook and visiting British actor Edward Warden penned a Black Cook which went round the country.

Poster for the “Black Crook” production 1866.

A silent film based on the Black Crook story was produced in 1916, with Australian ex-tenor Henry Hallam as Wolfenstein, E P Sullivan as Hertzog and Mae Thompson as Stalacta.

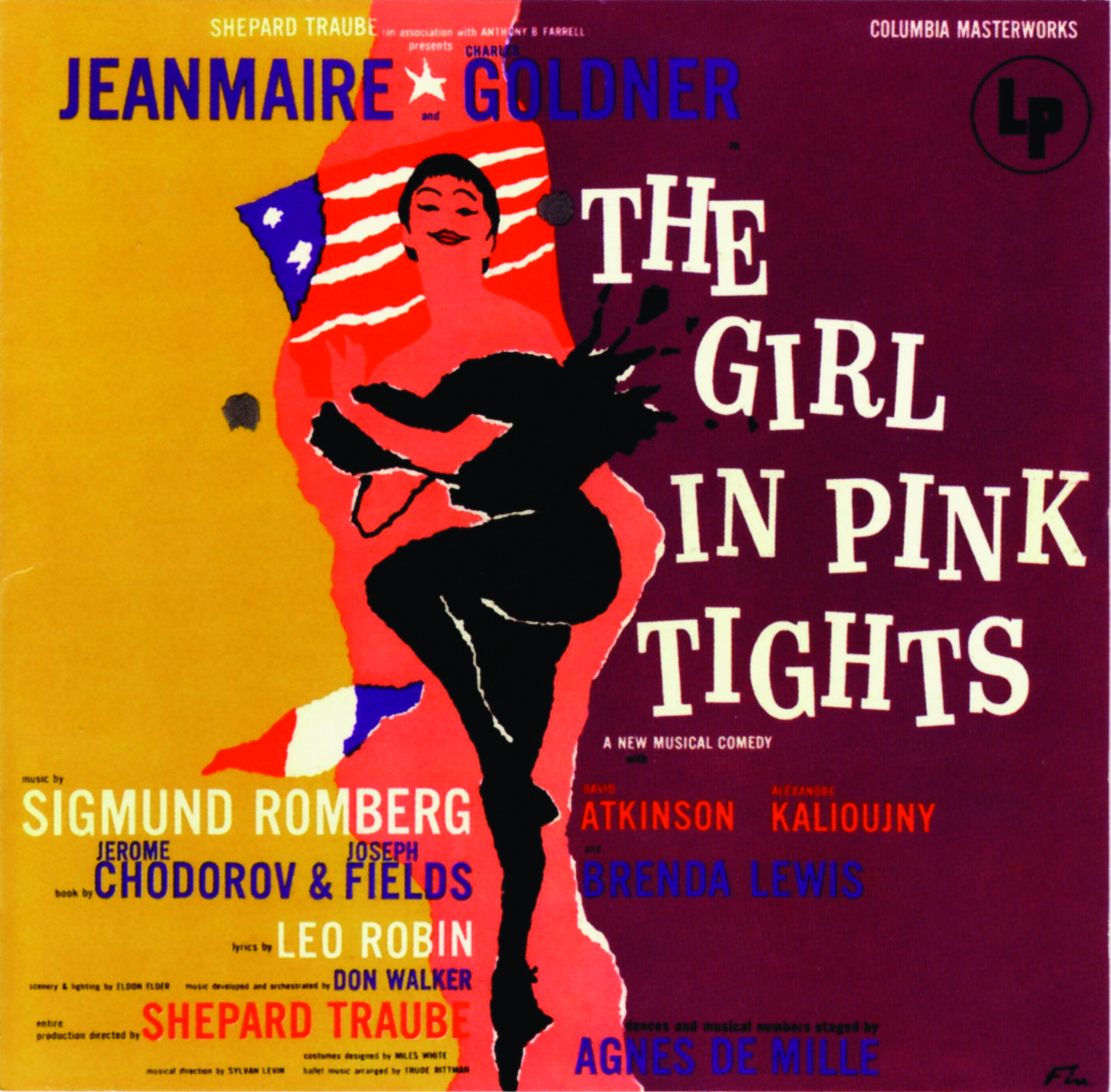

The favoured mytho-story of the creation of The Black Crook was used as the background for the show The Girl in Pink Tights (Sigmund Romberg/Joseph Fields, Jerome Chodorov Mark Hellinger Theater 5 March 1954).

LP cover of “The Girl in Pink Tights.”

Following the grand American success of the Black Crook, there was another Black Crook as a grand opéra-bouffe féerie in 4 acts by Harry and Joseph Paulton founded on La Biche au bois. Music by Georges Jacobi and Frederic Clay. Alhambra Theatre, London, 23 December 1872.

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897.

An early effort to reproduce in Britain the same kind of vast and spectacular grand opéra-bouffe féerie which was then popular in France, this version of the La Biche au bois legend owed nothing to its American homonym except its title. Lovely opéra-bouffe star Cornélie d’Anka starred as the vicious witch of the title out to thwart the enchanted Princess Desirée and her Prince, but the largest part of the evening’s entertainment was, as in the American show, given over to its physical production, its ballets and the low comic element as personified by author Harry Paulton as a comic vizier and Kate Santley (who had appeared for a while as Stalacta in the American Black Crook) as the heroine’s maid, in which rôle she delivered the show’s stand-out song ‘Nobody Knows As I Know’ in the overtly roguish style she favoured. The production, staged for Christmas, played until the following August.

A simplified version with revised text and music was successfully produced at the same theatre in 1881.

Film: (silent) US version Kalem (1916).

Advertisement for the 1916 silent movie version of “The Black Crook.”

For an update on the Black Crook saga, with much new information on the main players, click here for part 2 of Kurt Gänzl’s essay. For a background interview with playwright Joshua William Gelb about his version of The Black Crook (presented in New York City in 2016 for the sesquicentennial, click here.)