Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

16 June, 2015

There is a renewed interest in operetta internationally, not just the French and Austrian variety of the genre, but also its unique history on Broadway. The Jewish Museum in Vienna will deal with it next year in the exhibition Stars of David: The World of Jewish Sounds – Jews and Popular Music, Ethan Mordden’s new book on “The History of American Musical Theatre” entitled Anything Goes also contains large chunks of American operetta history. But the narratives are often confusing because they apply latter-day definitions of “operetta” to the productions of the 1860s that were very different – and crossed over rather effortlessly to burlesque, vaudeville, musical comedy, music hall and revue. We met with Richard C. Norton, author of A Chronology of American Musical Theater, to talk about these early shows, and to find out: where has the sex disappeared to in modern-day “family friendly” Broadway?

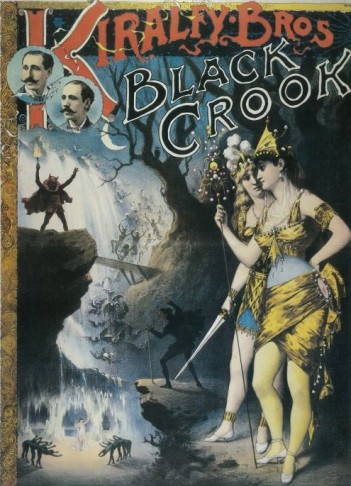

Poster for the “Black Crook” production 1866.

The 1866 show The Black Crook, which opened on September 12 at Niblo’s Garden in New York, is often seen by theater historians as “the first American musical.” Is that correct?

The story has often been told that The Black Crook, for the first time, combined the elements of musical comedy and ballet – with girls who “wear no clothes to speak of” as The New York Times noted. It was a big fairy spectacle, like a French opéra-féerie or the Drury Lane spectacles in London. The Black Crook became the first Broadway theatrical entertainment that ran for over a year. So it became a phenomenon, and a touch-stone. It came right after the end of the Civil War, so there was suddenly a huge amount of money floating around and there was a great sense of relief. You can see the success of this show as a kind of postwar celebration for New York.

Was it a kinky show with all these girls with “no clothes to speak of,” like the early French and Viennese operettas?

I think for a modern American audience it would be hard to see, from the printed text alone, what exactly was so radical about The Black Crook. I would seriously question whether there was anything particularly “sexual” or “sensual.”

But it was definitely a spectacle – with girls!

Did this milestone-work include cross-dressing made popular by European operettas?

I don’t think there’s much cross-dressing in The Black Crook.

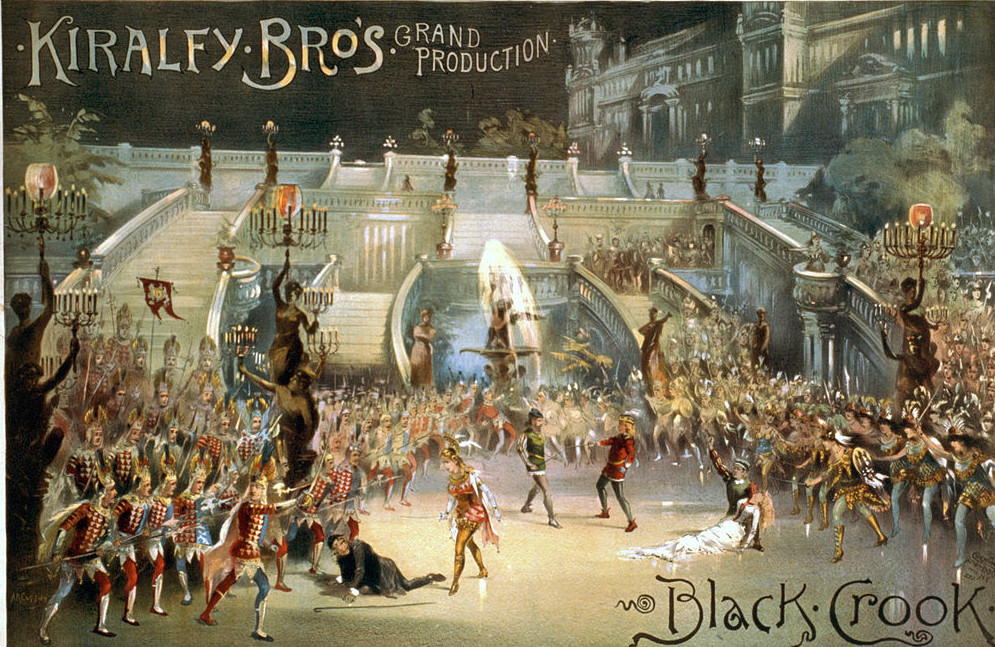

The finale of “The Black Crook” 1866.

What about minstrel-show elements?

It was not a black-face show. But the elements of minstrelsy and black-face could be integrated into any show of that period. The great heyday of minstrelsy did not really start until 10 years later, in the 1870s. You have to realize that in this country it was not legal for black actors to fraternize with white actors onstage, so you had white actors “blacking-up” to play black characters. But that was not part of the The Black Crook concept.

It wasn’t the first fairy spectacle on Broadway, was it?

No, there were earlier ones, but typically they would only run from one to six weeks. The Black Crook was a show at Niblo’s Garden, below 14th Street in the old theater district of New York, and it was an English language production with music by various composers.

The French actress Marie Desclauzas performed in the 1868 New York production of “Genevieve de Brabant” with her “joli jambes.” (Photo: Kurt Gänzl Archive)

A year later, in 1867, you get the first European operettas by Offenbach: La Grande-Duchesse with Lucille Tostée from the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens made the start, then followed Genevieve de Brabant in 1868, performed in French with female actors also imported directly from Paris. One reviewer called it the most “revolting mass of filth that has ever been shown on the boards of a respectable place of amusement in this city.” How does that compare to The Black Crook and the girls-without-clothes there?

Remember that this Offenbach was performed in French at first, and not all Americans spoke French. So it was probably a slightly more elite audience originally. Since Genevieve came from a different theatrical tradition, the humor and satire of Offenbach might have been lost on an average American theatre-going audience. However, the “filth” of the scanty costumes certainly recommended it to a wider American, non French-speaking audience. Also, consider that the papers that pronounced such verdicts might have done the producers a favor. Such a denouncement actually recommended the production to audiences that were in-the-know.

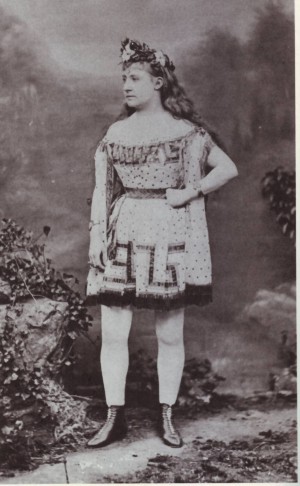

Lydia Thompson as Ixion.

A year later, Lydia Thompson came to Broadway with her troupe of scandalous “British Blondes” to introduce a radical kind of burlesque with Ixion – that was like an Offenbach operetta but did not have newly composed music, instead its score recycled popular songs (including some by Offenbach). Ixion was a theatrical and commercial sensation. Did the Americans copy the model?

The Americans would do something like a knock-off, yes, a somewhat cheaper version or imitation. It would not have been nearly as inspired or nearly as adventurous though.

Why not?

You have to realize that America had an inferiority complex. Great art – whether it was music, drama, literature, ballet, paintings – all tended to originate in Europe. America was perceived as a cultural wasteland, the receiving end of these great things. Americans might try to re-interpret genres and styles in their own way …

Including the “filth”?

Including the filth. But it didn’t have the same level of excitement, authenticity, and cachet. It’s sort of like saying: “Do you want to look at my filthy French postcards?” Instead of: “Do you want to see my filthy American postcards?” The assumption was that because it was French it was the “real” thing. It was much more titillating, not a cheap knockoff. It’s like a purse made in China today: a cheap copy of a designer original.

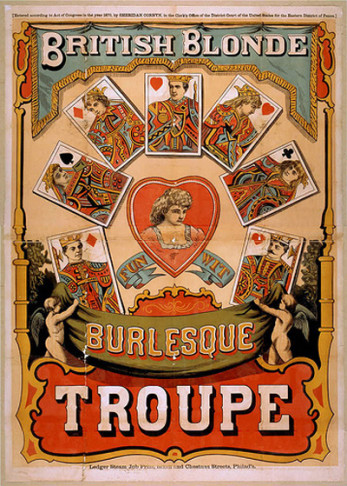

Advertisment for the British Blondes burlesque troupe.

When the Americans copied French operetta or British burlesque, they sanitized them and made them “family friendly.” Wasn’t the whole point of these genres that they were not family friendly?

The librettos here in America never had the same satiric edge as the French originals. Offenbach’s librettists oftentimes satirized the peccadillos, the sexual behaviors, the political scandals that were indigenous to Paris. That sense of humor and the particulars of who these people were was lost on Americans. So what did they do? They made fun of Tammany Hall, which was the reigning political organization in Manhattan. Or the Irish, the Germans, the Jews, the blacks … By the time you re-purpose the humor from something that was originally French, and try to adapt it to something that is essentially American, it’s a different joke.

At least there was no censorship in America. You could be much more free and take more liberties than in Europe.

It isn’t that there was no censorship; only the censorship was indifferently and inconsistently applied, it was left of local authorities in each jurisdiction.

For example Boston was famously puritanical, so many shows that were tried out there had to be “cleaned up” for Bostonians, because the press, the police and the audience expected things to be more “sanitized.”

But there was no Lord Chamberlain.

No, there was no single arbiter of taste like in Great Britain.

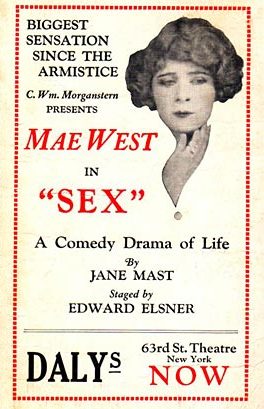

Poster for Mae West’s 1926 play “Sex”: “A Comedy Drama of Life.”

So who closed down a show?

Most likely, there would be a lawsuit filed at the New York municipal court by any number of self-appointed do-gooders or ministers who alleged something was “unacceptable” public entertainment. As late as 1927 the Mae West show The Drag was closed down by the police because it showed “sexual situations” and “homosexuality.” That was not permitted on the stage, just like you could not depict real nudity until much later. Often producers tried to test these boundaries, to see what they could get away with. Sometimes the amount of press they got because of scandals was what sold a show. If the producers, writers or performers were tried in court and found innocent, the surrounding publicity would be great advertisement for their show.

If Boston audiences expected shows to be “sanitized,” audiences in New York were considered more open and cosmopolitan. What about Hollywood?

The “pre-code” talkies from 1929 to 1934 were notoriously free of censorship. You could have a woman with children out of wedlock etc. It wasn’t until the Hays Code (or “Motion Picture Production Code”) came in that all of that changed. As a result, you had Cole Porter songs in the 1930-40s that could be performed on stage on Broadway, but were considered unacceptable for airplay and use in Hollywood.

Back to the 1870s: were the genres operetta, vaudeville, burlesque and musical comedy strictly divided?

No. Some of the theaters had informal resident companies. Take for example successful producers such as Harrigan & Hart in the 1870s and 1880s. They tended to use the same stable of actors from year to year, as did Weber & Fields in the 1890s and 1900s. They would open a new show in September or October, to run the season, but when it closed early, the performers often moved to other theaters to work in other genres. There was a great mix in all directions. Vaudeville presentations were generally a variety bill, consisting of a series of acts that would change on a weekly basis. Whereas in a revue, the order of acts would largely be set on opening night and remain intact for the run, unless there were cast changes or special material interpolated for stars such as Al Jolson or Eddie Cantor who wanted to do their favorite new song. This kept the shows fresh.

Operetta soon focused on “romance” and spectacle rather than “filth,” it was also a narrative genre. Still, you could get comedians and vaudeville acts in certain operetta productions and operetta songs in vaudeville, always depending which performers were hired.

Original sheet music cover for the 1927 hit “Show Boat.”

Florence Ziegfeld later would not only produce his Follies once a year, he would also do big book-musicals and operettas such as Friml’s Three Musketeers in 1928 or Kern’s Show Boat in 1927. The Messrs. Shubert were famous for buying continental operetta, especially the next German-language operetta, and bring it to New York with musical comedy stars in the lead roles, with mashed-up scripts, scores and many interpolations by American musical comedy writers. The Shuberts had to stop during World War 1. It wasn’t until the early 1920s that more German-language operettas were brought back to Broadway, again in a very musical comedy performance style that is similar to what you hear in Show Boat. In that era, people like Irving Berlin did not write operetta, but revue and musical comedy. On the other hand, Friml wrote operetta and musical plays. And Romberg wrote operettas, revues and musical comedies. There was constant cross-over in all directions.

Was vaudeville seen as low-brow entertainment?

Not necessarily. There were a number of venues on the Bowery, on the lower East Side, which were basically Music Variety and Music Halls. Working men would go there, unescorted women would appear “suspect.” These shows – that mixed musical styles – would be different from Tony Pastor’s vaudeville. Pastor started in the 1880s, he made famous the notion that his shows were vaudeville that was “safe for women and children.”

He instigated the week-day matinee so that women could go to it during the day and get back home before dark.

After the successful early Offenbachs and other European imports, were there original American operettas?

There were, but they are largely forgotten today. You have composers like Gustav Kerker in the 1890s: he was German born, but wrote a number of operettas for Broadway, among them the famous Belle of New York. You have Reginald de Koven who wrote Robin Hood in 1891, the longest running musical show of the decade. Many of the other operettas of that era are not remembered today because they are musically uninteresting.

Did these shows continue the “filthy” Offenbach tradition?

They might have been frivolous, but they weren’t filthy!

Did these American operettas continue the European cross-dressing tradition of the genre?

Not especially. You’d only find cross-dressing in a sort of Shakespearian format, e.g. when the daughter has to dress up as a man to be close to her beloved in the army, or the Yentl narrative. There’s nothing terribly naughty about it, as had been the case with Thompson’s British Blondes.

What became of Thompson’s burlesque tradition and cross-dressing?

There is a tradition of cross-dressing in America, whether it’s Teddy Hart in the Harrigan & Hart shows of the 19th century, Milton Berle on television, or a man named Julian Eltinge who was a female impersonator in Broadway musicals. You have Savoy & Brennan who appeared in drag on Broadway.

But these cross-dressers were more known for crude jokes and slapstick humor, not for sexual liberties and acts that revolutionized notions of gender.

Operetta theaters in Europe were originally a place to pick up girls, and boys. What about New York?

There were various locations in the Times Square theater district which were known as homosexual meeting-places, the most famous was the Astor Bar, which was the bar at the Astor Hotel on 44th St., just West of Broadway. It was a “gay friendly” place you could go to after a show and pick up chorus boys.

The Astor Hotel in New York. (Photo: United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division)

What about the chorus girls?

There were bars where you could meet them too. In the 20th century you wouldn’t pick up “trade” in the theater itself, like in London’s Alhambra back in the 1870s, but there were places near the theater for that purpose; just like there was that famous brothel right behind the Theater an der Wien in Vienna which operated till the 1940s.

When Genevieve de Brabant came to New York in 1867 it was a ground-breaking, non-normative form of theater. Was operetta, later, ever seen like that again?

American operetta in the 20th century was never truly radical or revolutionary again. Not even satirical. It quickly became the province of romance and spectacle. Even The Merry Widow is pretty “safe,” musically and thematically. And that became the prototype for operettas in the 20th century, just like Gilbert & Sullivan had been the prototype for operettas from 1879 onwards. Many of the American musicals and operettas attempted to be like G&S but were conceded – by American critics – to be second-rate knock-offs. And neither G&S’s originals nor the knock-offs were especially radical in the Offenbach sense of the word.

Scene from “Miss Hook of Holland” by Paul Rubens.

Where there more London imports?

Fewer and fewer: shows like Rob Roy or Miss Hook of Holland were successful on Broadway. A handful of the Edwardian titles had respectable runs here in the first decade of the 20th century. But they were far surpassed by the Viennese titles. Their dominance only ended with WW1. Had the war not happened, the German dominance of the operetta market would have undoubtedly continued. Maybe America would even have experienced “jazz operetta” like you had in Europe. Instead, we got home-grown “musicals” with jazz and turned “operetta” into mostly nostalgic fluff. Fluff that was still very successful, by the way, if you think of Romberg’s Student Prince and Desert Song or Friml’s Rose-Marie. They were some of the biggest hits of the 1920s.

These prototype Broadway operettas contain at least one “jazz” number each!

I think the styles were somewhat uncomfortably mixed in America. In the 1960s you had the phenomenon where a traditional musical would have to have the requisite rock’n’roll number interpolated, just to show that the producers were up-to-date and “hip.” I am sure that back in the 1920s you could have an operetta with an on-stage cabaret number, which would be very “musical comedy” with concessions to jazz. After that, you went back to the safe and secure world of romance which operetta came to stand for.

There was a burlesque version of The Merry Widow ….

Yes, it was a burlesque in the sense of a parody. It was a Joe Weber show called The Merry Widow and the Devil. It had an original score, so it was not music by Lehár. Joe Weber toured it around the country. It was a loosely structured parody, just like a Weber & Fields send-up of a Sarah Bernard play.

A scene from Weber’s Burlesque “The Merry Widow and the Devil,” 1909. (Photo: Museum of the City of New York)

When does burlesque turn from being a parody to a strip show?

That must have changed after WW1, starting in the 1920s. That’s when the concept of the word in the English language changed.

Could you still have operetta songs in them, as a strip number?

Not likely, no, not very likely!

In the “filthy” and stripped-down early days of operetta, some critics in Britain complained that these shows were a Jewish plot to destabilize family life. Is there an American equivalent to such anti-Semitic attacks?

No, the press in America seems to have consciously overlooked “Jewishness” in the operetta or musical comedy business, unless they talked about Yiddish musical theater on Second Avenue. There was a strong tendency towards assimilation of Jews within the entertainment business, especially in New York. But you could always have a far right-wing point of view, even in America, especially when it comes to “family values.” There was a producer in the 1920s called Eddie Dowling who produced a musical entitled Honeymoon Lane: an unremarkable show, mostly forgotten now, but it outran the season. I remember seeing a full-page advertisement saying: “Acceptable for the entire family!” As if to differentiate it from other shows. Even if you see a Disney film nowadays it will say: “Acceptable family entertainment.”

Is that what operetta in America has become too?

Operetta would not be family entertainment, because children would be bored to death by all that romantic stuff.

But you could draw a direct line from The Black Crook to the current Disney shows?

As far as the spectacle elements are concerned, yes. But the moment you get to the sentimental ballads, that are also the key to our current post-Offenbach understanding of operetta, children start to squirm and grow restless. So the romance, which is the true province of operetta now, is not kid-friendly.

Kids might enjoy the original “filth” of operetta ….

Where is the sex in Aladdin or The Lion King? It’s largely sublimated into the narrative. If you go and see Aladdin, then yes, the female lead shows some flesh in her bare mid-drip, and she’s cute. But she is no more cute than the boys. It’s all very “safe.”

Do you need to be “safe” to reach a mass audience?

Yes, so Broadway is not likely to ever fall for Offenbach on a grand scale again.

A cartoon in the London paper “The Day’s Doings” from 8 October, 1870, giving an impression how these early operettas were performed. (It might look pretty harmless from this angle, but not from the stalls.)