Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

13 December, 2020

“The Art of Operetta“ is the headline on the cover of the December issue of Gramophone magazine from the UK. Under that headline: a historic drawing of The Merry Widow. I admit my heart skipped a beat because I thought: finally! In his editorial, chief editor Martin Cullingford says: “If operetta has rarely been granted such prominence in our pages, I hope Richard Bratby’s superb survey of this fascinating genre makes merry amends.” Right under that, Mr. Bratby himself states: “I never need much encouragement to talk about operetta. […] It’s my contention that we’re living through a renaissance of the genre.” A genre he calls “wonderful”, but “misunderstood”. My curiosity was aroused, and I bought my first Gramophone issue in years.

The December 2020 issue of “Gramophone.”

Okay, there’s a bit of a personal back story here. I used to have a subscription to Gramophone in my twenties (i.e. a long time ago), and the thing I loved most about this special interest magazine were the reviews of historical opera singers and their recordings. A senior critic described the glories of legendary tenors, sopranos, baritones etc. every month, at a time when the “Lebendige Vergangenheit” albums came out on Preiser. I sucked up these reviews with religious fervor. Because the critic regularly pointed out why these legends of the past surpassed many modern day interpreters in terms of vocal personality, sense of style, glorious details that set them apart. At the time I used to believe this critic blindly; if he said XY was great, I rushed to the record shop and bought the CD. Till one day he reviewed a new Verdi opera which had Andrea Bocelli in the tenor lead. I think Zubin Metha conducted. Anyway, I was curious as to how this super critical critic would compare Mr. Bocelli as Manrico to all the greats of the past that he usually raved about. To my surprise he raved about Bocelli too, which made me listen to this Trovatore the next day in a record shop and then made me cancel my subscription. (Wondering how much money this famous critic might have been paid to write such a glowing article that contradicted everything he had previously stood for.)

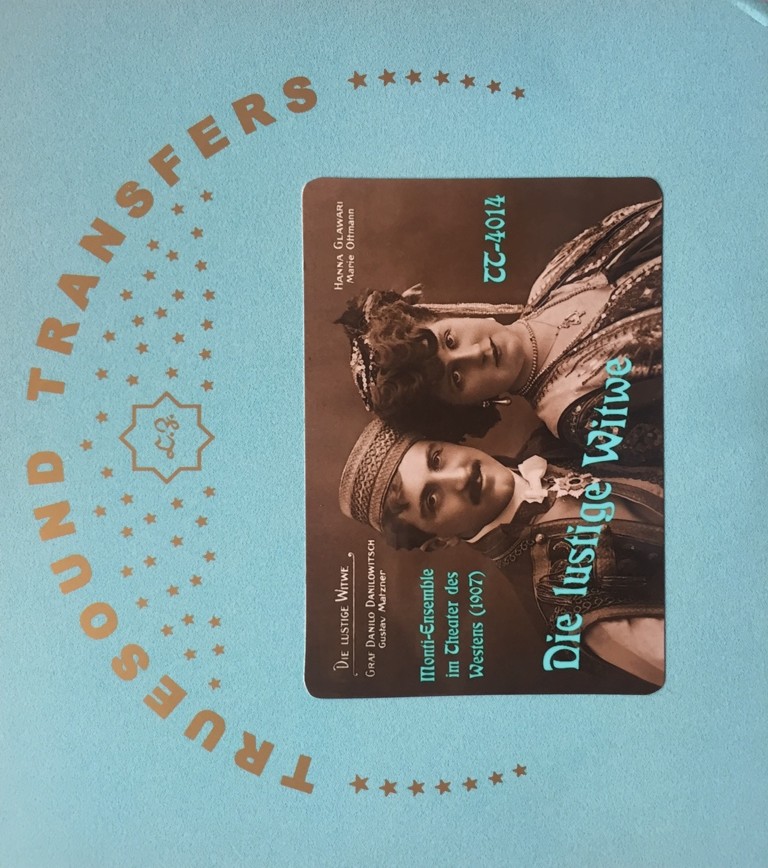

So fast forward 25 years. And I’m back buying a Gramophone issue, optimistically hoping it might bring new insights into the operetta market on disc (it’s called Gramophone after all). And since The Merry Widow is shown on the cover, I thought there might be a discussion by the esteemed Mr. Bratby of the recent “first ever” CD release of the first ever complete recording of Lustige Witwe, made in Berlin 1907. Surely a landmark album, then and now, restored by Truesound Transfers in such a way that you almost feel the singers standing next to you.

The cover of the Truesound Transfers “Lustige Witwe” album.

On the same album, you also get the original 1905 Vienna cast, i.e. Louis Treumann and Mizzi Günther in superbly restored highlights. Demonstrating a style of operetta singing that is as far removed from any modern Witwe recording as possible, because back in 1905/7 these were not opera singers with pretty voices, but character actors with a grotesquely exaggerated comic style. The men especially come across as something like “Borat Does Operetta,” in a good way. They also make everything sound so easy, so intelligent, so much fun. And so absolutely unique.

If we look at the reviews of the original London and New York productions, that catapulted The Merry Widow to international stardom, the lead roles were also taken by comedians who couldn’t sing (Joseph Coyne and Donald Brian) and by dazzling looking ladies who did not perform Richard Strauss or Puccini on alternative nights (Lily Elsie and Ethel Jackson).

Lily Elsie and Joseph Coyne in ‘The Merry Widow’, 1907. Elsie and Coyne are playing the parts of ‘Sonia’ and ‘Prince Danilo’ respectively.

Yet at the start of the Gramophone feature Anastasia Belina, co-editor of the recent Cambridge Companion to Operetta (2020) says: “Operetta calls for the same kind of singer as in opera. The only difference is that the singer is also expected to act and dance skillfully.” This segues into a statement from soprano Soroya Mafi who is currently preparing the title role in Reynaldo Hahn’s Ciboulette, has sung Mabel in Pirates of Penzance and Musetta in La Bohéme. She, too, thinks the singing is the same in opera and operetta. According to her, the “physical act of delivering dialogue” and comic timing are the difference, and the challenge. She tried to solve that challenge herself by going to a speech therapist. Not to an acting class. Which brings me back to the Merry Widow: that 1907 recording from Berlin includes all the dialogue, proving how important this element was/is. And the opening XXL-photo in Gramophone shows star actress Dagmar Manzel in Ball im Savoy. Like few others in recent memory, Manzel has proven how much fun the dialogue in operetta can be, how important it is, and how important it is to be able to deliver it brilliantly next to the music and the dancing.

Of course it would be a dream to have Manzel as a Merry Widow one day (any day!) and show Mr. Bratby or Anastasia Belina that singing Lehár (or Offenbach, or Johann Strauss, or Paul Abraham) does not call for “the same kind of singing as in opera.”

In the feature, you get two more photos of Miss Manzel, from the Oscar Straus operetta Die Perlen der Cleopatra, in which she slipped into a role written for Fritzi Massary. Who, in turn, is also represented on the Truesound Transfers album as Hanna Galwarios [sic] from the famous Erik Charell jazz version of the 1920s.

The one and only Fritzi Massary.

Massary’s Witwe tracks (with new lyrics and newly arranged songs) are available on many other albums, too, not to mention YouTube. They are kind of legendary, but they are not mentioned in a single sentence here. Neither is the question raised why the Manzel style of singing operetta has brought on a renaissance of the genre? And for a Gramophone magazine making such opulent use of these production photos you might wonder why no one asks where the CDs and DVDs of Manzel operetta performances are? (Or why there aren’t any.)

In part 2 of the feature, Mr. Bratby speaks with Barrie Kosky, the man who staged Dagmar Manzel’s super hits at Komische Oper Berlin, together with Adam Benzwi as musical director and Otto Pichler as choreographer. Mr. Kosky doesn’t mince words, and even if I don’t agree with everything he says here, he makes strong and emotional statements that prompt you to react. It’s not the typical blabla so many others cultivate to not “irritate” anyone.

Barrie Kosky, artistic director of the Komische Oper Berlin. (Photo: Jan Windszus Photography)

Mr. Kosky mentions that he saw Joan Sutherland in Merry Widow as a child in Australia and recalls his reaction: “Appalling!”

For him, the “deluxe, grand opera approach to operetta” – as celebrated by Sutherland and almost everyone who gets a word in at Gramophone – has “malign roots”. In Kosky’s words opera singers, after the war, “decided that it was nice to have a holiday and make some money by doing an operetta album, and they put the last nail in the coffin.”

He calls for a revolution comparable to what happened in Baroque music a few decades ago. (A battle cry first expressed in 2005 at the conference Operette unterm Hakenkreuz.) “I mean, listen to the way Tauber sings operetta – so spectacularly good”, says Kosky, “but listen to Jonas Kaufmann trying to do the same music and it’s a disaster.”

The obvious next question would be: why is it such a disaster? Surely Mr. Kaufmann has the perfect voice for Tauber roles, but he doesn’t have a clue about the style. Maybe because he’s a Gramophone reader and has been told by all the experts… well, you know the rest.

In a final punch Mr. Kosky says “I love Nicolai Gedda singing French and Italian opera, but his recordings of operetta are catastrophic, like Elisabeth Schwarzkopf’s, I mean, it’s like getting Emma Kirkby to sing Wagner.” Mr. Bratby replies “ouch” to this. But he doesn’t pick up the point to discuss all those EMI operetta recordings with Gedda and Schwarzkopf, he doesn’t put things in perspective for his readers in his elegantly written article.

I guess you could call it a missed opportunity. And that’s probably what made me so mad. Or sad. Gramophone is not going to have another big feature – let alone a cover story – on operetta anytime soon. Whether this six page special will bring on a “revolution” of any kind seems doubtful to me.

At the end of the article you get five operettas on disc and DVD as a recommendation, ranging from Lehár’s Land des Lächelns in an “atmospheric art deco staging” by Andreas Homoki to Heuberger’s Opernball from Graz Opera. There’s Die Herzogin von Chicago (from Decca’s “Entartete Musik” series) and Sullivan’s Haddon Hall (no idea how that slipped into there), plus Marc Minkowski’s La Périchole on Palazzetto Bru Zane.

What more is there to say? Other than “ouch”.

For more information on the Gramophone December issue, click here.

You quite reasonably regret the fact that Richard Bratby misses the opportunity to explore what is at stake in Kosky loathing a way of singing operetta that Bratby loves. But this issue arises for you too and you do not discuss it (at least not in this article). For Kosky loathes Schwarzkopf’s operetta singing – singing which I believe you love.

The art of singing operetta has gone out of style. The skills neeed to perform these stage works has disappeared for the most part in live performances and recordings.The Viennese operettas of it’s golden age and later it’s silver age are still staged but in strange arrangements. Operetta singers are not Opera stars but character singing actors. That is what has been lost over time.Old recordings help us see what has been lost.