Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

23 October, 2016

Here is a splashy new biography of “Broadway’s Greatest Producer,” Florenz Ziegfeld, written by the team of the Brideson sisters, Cynthia and Sara. Published by the University Press of Kentucky, it offers 500+ pages of a “lively and well-rounded account” of the “famed producer as a father, a husband, a son, a friend, a lover, and an alternatively ruthless and benevolent employer.” It also offers an interesting new form of academic writing. Let’s call it the “re-sampling method.”

Cover for “Ziegfeld and His Follies,” published by University Press of Kentucky.

Cynthia and Sara Brideson – co-authors of Also Starring… : Forty Biographical Essays on the Greatest Character Actors of Hollywood’s Golden Era, 1930-1965 – have managed the quite admirable task of going through most of the relevant published literature on Ziegfeld and Broadway history, scanning old and new publications, and turning the facts and opinions they found there into an elegantly readable new book that is like a huge mosaic of (credited!) quotes. This gives the reader the pleasant feeling of being on top of the game, so to speak. It also makes the reader feel extremely erudite, since he’s practically handed the entire Ziegfeld literature as a new, coherent, and fluent “best of” narrative. However, there does not seem to be anything decidedly new, something that the Brideson sisters found themselves in terms of new documents, new research, new interpretations. They didn’t even took the trouble to dig up original reviews of the various Ziegfeld productions between 1896 and 1932 to paint a detailed picture of how these shows were received by their contemporaries; or at least this is not done on a grander scale worth mentioning. (Of course there are various short citations from historic newspapers, probably taken from already existing books.)

Poster for “The Sandow Trocadero Vaudevilles,” produced by Ziegfeld in 1894.

Merely summing up the many Ziegfeld related publications, and commenting on all of them from a 2015/16 perspective, could have been a worthwhile enterprise. The book starts off promising with the Bridesons describing how Ziegfeld discovered bodybuilder Eugen Sandow and begins his theatrical producing career – that later became so famous for “Glorifying the American Girl” – with the presentation of the near-nude man who got society ladies erotically excited with his bulging biceps. The fact that Ziegfeld discovered the importance of the female audience in the 1890s and the importance of luring them into a theater with masculine objects of desire could have been a study in itself. But it soon turns out that the Bridesons prefer to refrain from any in-depth discussion of such like matters.

1898 poster showing Anna Held’s eyes.

The same applies for their description of Anna Held, Ziegfeld’s first wife and superstar. Their complicated private and professional relationship is dealt with at length, but never do the Bridesons offer any kind of insight into the role of women “from Paris” in late 19th century American Theater. And they don’t examine how the “open” marriage of the two, obviously not in accordance of the approved moral standard of the era – was discussed and evaluated by contemporaries. Or Miss Held and Mr. Ziegfeld themselves.

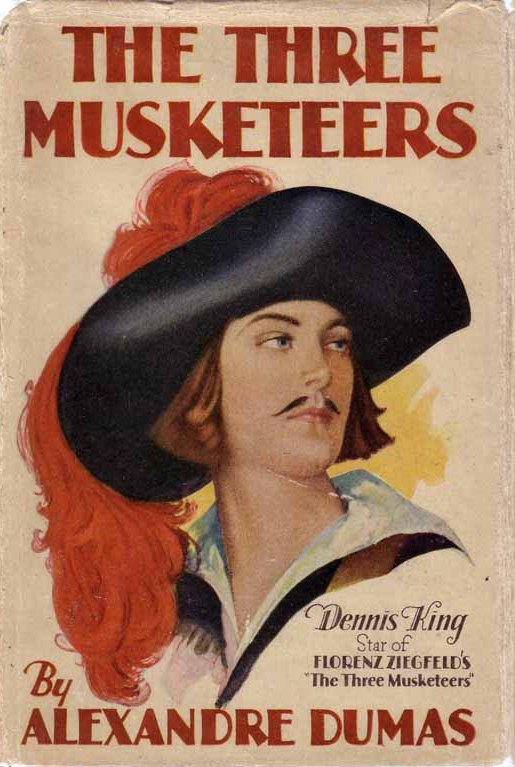

Dust jacket for a book version of Dumas’ novel from 1928, with Dennis King from the Ziegfeld production on the cover. The show ran for 318 performances on Broadway.

When it comes to the operettas Ziegfeld produced, most famously The Three Musketeers with music by Rudolf Friml and Bitter Sweet with words and music by Noel Coward, the Bridesons have absolutely nothing to say about the genre in the 1920s and how “operetta” as envisioned by Ziegfeld was different to other Broadway shows at the time, including the famous revues Ziegfeld presented as his Follies? They also don’t bother to describe in any details how these operettas differed from Ziegfeld’s Show Boat, their direct timeline neighbor. Instead, Musketeers is called “an operatic version” of the classic Alexandre Dumas tale, and later Bitter Sweet and Musketeers are labeled “light operetta” – a genre that, according to the Bridesons, didn’t stand a chance with audiences after the Wall Street Crash and the dark economic times that ensued. I must confess that I found this extremely disappointing. Obviously, there is no mention of Erik Charell who was inspired by Ziegfeld’s Musketeers to present his own Drei Musketiere a year later in Berlin, with a very similar score written by Benatzky à la Friml.

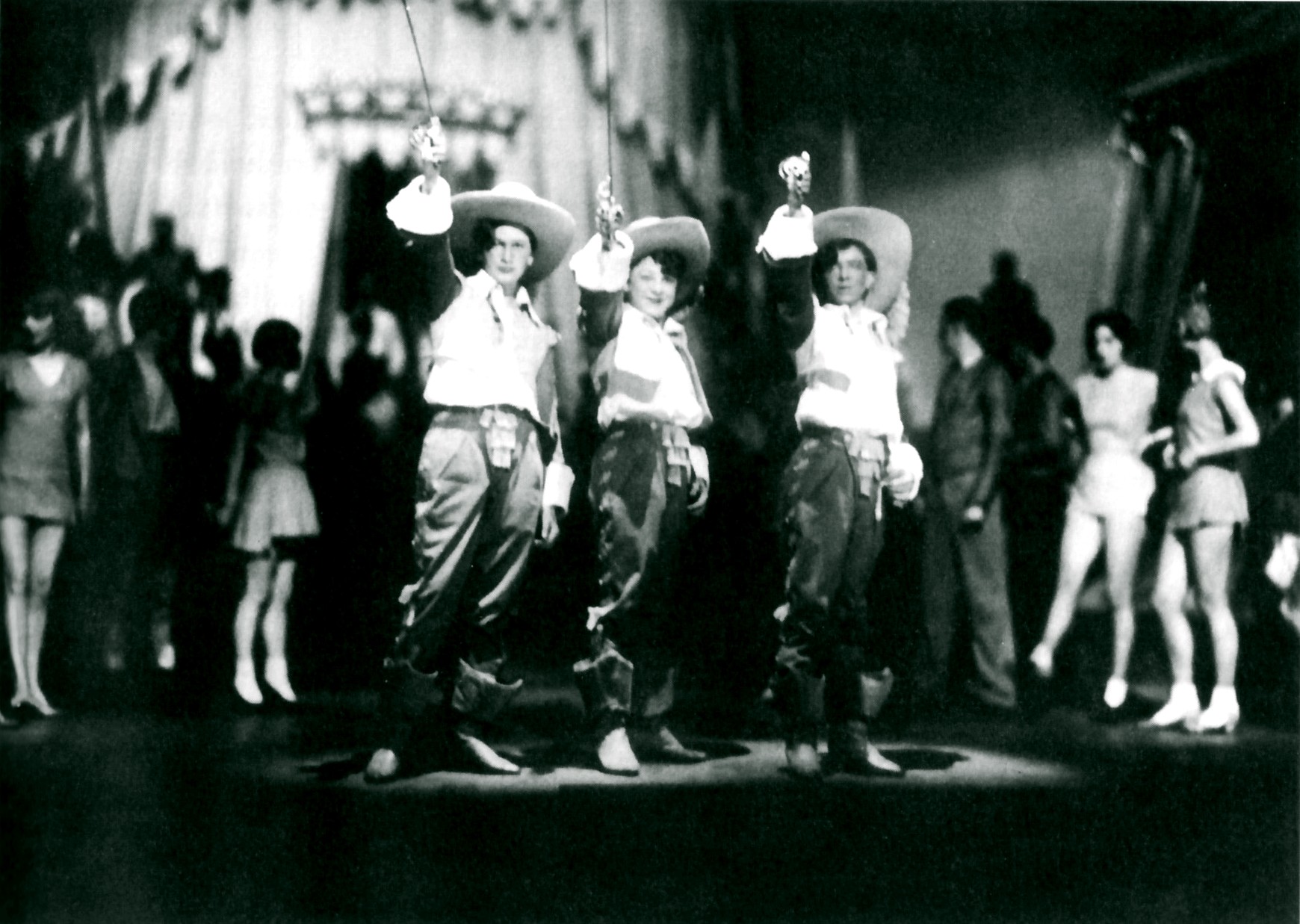

Erik Charell’s Berlin version of the “Musceteers” at the Großes Schauspielhaus, starring Alfred Jerger, Max Hansen and Siegfried Arno (from left to right). (Photo: Archive Operetta Research Center)

Also, somewhat irritating is the fact that even though a lot of literature is recycled in this new book, some remarkable recent research has been completely left out. To give just one example: in 2004 Andrea Most wrote extensively about the Eddie Cantor vehicle Whoopee, produced by Ziegfeld, in Making Americans: Jews and the Broadway Musical. None of Most’s fascinating insights into this show, none of her points about the famous “operation” Cantor talks about throughout, pulling his pants down to show everyone to show his “difference” (= circumcision), and none of the homosexuality dealt with as a running gag is picked up by the Bridesons. As a matter of fact, they seem to have nothing much to say about Whoopee at all, except that is opened in December 1928 and was a huge hit. That Rosalie, a month earlier, contained a score by operetta grand master Sigmund Romberg and George Gershwin is not a cue for comment either.

Poster for the film version of “Whoopie,” starring Eddie Cantor.

Where does that leave things? For a well written summary of what has been written about Ziegfeld thusfar, this is an attractively packaged new book. But it will leave you seriously wanting more details and a more in-depth descriptions of practically everything. Also, you have to live with statements such as this one towards the end: “The Phantom of the Opera (1988), The Lion King (1997), and Wicked (2003) are only a few more examples of plot-driven musicals that can trace their roots to the foundations laid by Ziegfeld.” If you expect an explanation for this interesting claim, then Ziegfeld and His Follies is not the book for you.

Cover for the 1993 “The Ziegfeld Touch.”

It does offer a list of all Ziegfeld shows (which you can also find on the International Broadway Database), and a two-page “Selected Bibliography” that offers more titles than the current Wikipedia page on Ziegfeld does. Among them are Richard and Paulette Ziegfeld’s The Ziegfeld Touch: The Life and Times of Florenz Ziegfeld (1993) and Ethan Mordden’s Ziegfeld: The Man Who Invented Show Business (2008). If you already have these books, you might want to stick with them rather than investing in this new hardcover publication.

Cover for Ethan Mordden’s 2008 “Ziegfeld” biography.

There would be more to say about Florenz Ziegfeld in the future, whether it’s a feminist or a queer reading of his life and works, an account of Ziegfeld and People of Color in his productions, and many other highly topical questions worth discussing. The Bridesons chose not to go near any of these topics, only mentioning them in passing (if you’re lucky). It’s kind of the Ethan Mordden approach, already perfected in 2008. You could say, this is the expanded and enhanced version of the same style. Where Mordden offens a rear view of the glorified American Girl, the Bridesons go full frontal.

I’m sorry you didn’t find my sister’s and my book satisfactory. We did use new material, specifically letters between Ziegfeld and Billie Burke. We were only 22 when we wrote the book and had no intention of making it a dense read on topics like feminism. My sister Sara took her life two weeks ago, partly due to our utter and complete failures as writers. We wrote one other book after “Ziegfeld” but needless to say, I will not be writing any others. Sara and I used to love writing but after having it picked at it and scorned, I wish we would’ve just stuck to writing for fun. Some people can’t take criticism that isn’t constructive, and Sara, as am I, are some of those people.