Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

10 January, 2021

When the Shakespeare adaptation Swingin‘ the Dream opened on Broadway in 1939 it followed Erik Charell’s earlier XXL-sized Broadway hit White Horse Inn, a new version of his former Berlin success Im weißen Rössl, which had opened in 1930 and then conquered the world. Charell’s reworking of A Midsummer Night’s Dream pretty much functioned the same way as White Horse Inn: he used existing hit songs and combined them with newly composed material, and he presented a culture clash story. In Rössl the irreverent tourists from Berlin are confronted with the Austrian “natives.” In Swingin’ the Dream, the action is relocated to late 19th century New Orleans where the “white” local dignitaries and lovers are confronted in a “Voodoo Wood” with the “black” world of the fairy kingdom and a group of African-American workers who are practicing their “Pyramus and Thisbe” play. Bringing such a large and star studded black cast to Broadway – which included Louis Armstrong as Bottom, Maxine Sullivan as Titania, comedian Moms Mabley as Quince, and the Dandridge Sisters as fairies – was unusual. And it didn’t fare well with white audiences. Swingin’ the Dream closed after only a few performances. It was forgotten afterwards for decades. Till the Royal Shakespeare Company now decided to reconstruct the work and present “A Concert of a Work in Progress” online.

The jazz band that played the “Swingin’ the Dream” music at the 2021 RSC concert. (Photo: RSC / Screenshot)

I must confess I was very excited when I first read about this in a big New York Times article. Because as far back as 2007 I published my own big Erik Charell essay in the book Glitter and Be Gay: Die authentische Operette und ihre schwulen Verehrer, i.e. a book about the intersection of homosexuality and operetta.

The cover of the “Glitter and be Gay” book with Charell’s lover Louis Douglas seen bottom right.

Since Erik Charell is one of the most famous gay operetta directors and producers, his career at Großes Schauspielhaus in 1920s Berlin was presented, his early “Tonfilmoperette” Der Kongress tanzt (1931) which was his ticket to Hollywood and out of Germany before the Nazis took over in 1933, but also his career in the USA was outlined, plus his triumphant return to Germany with Feuerwerk (1950), as the only post-WW2 operetta that permanently entered the repertoire. In my essay, Swingin’ the Dream is mentioned and briefly described as another of Charell’s innovative attempts to revolutionize the genre operetta – with jazz music (as he had done in Berlin) and with a cast that didn’t conform with “heteronormative” standards. In Berlin he had hired Wilhelm Bendow and Claire Waldoff as a gay-and-lesbian double conference for his revues, he had also included his lover Louis Douglas (of La Revue Negre fame) in his shows, as well as various other black artists, e.g. in his adaptation of Franz Lehár’s Die lustige Witwe.

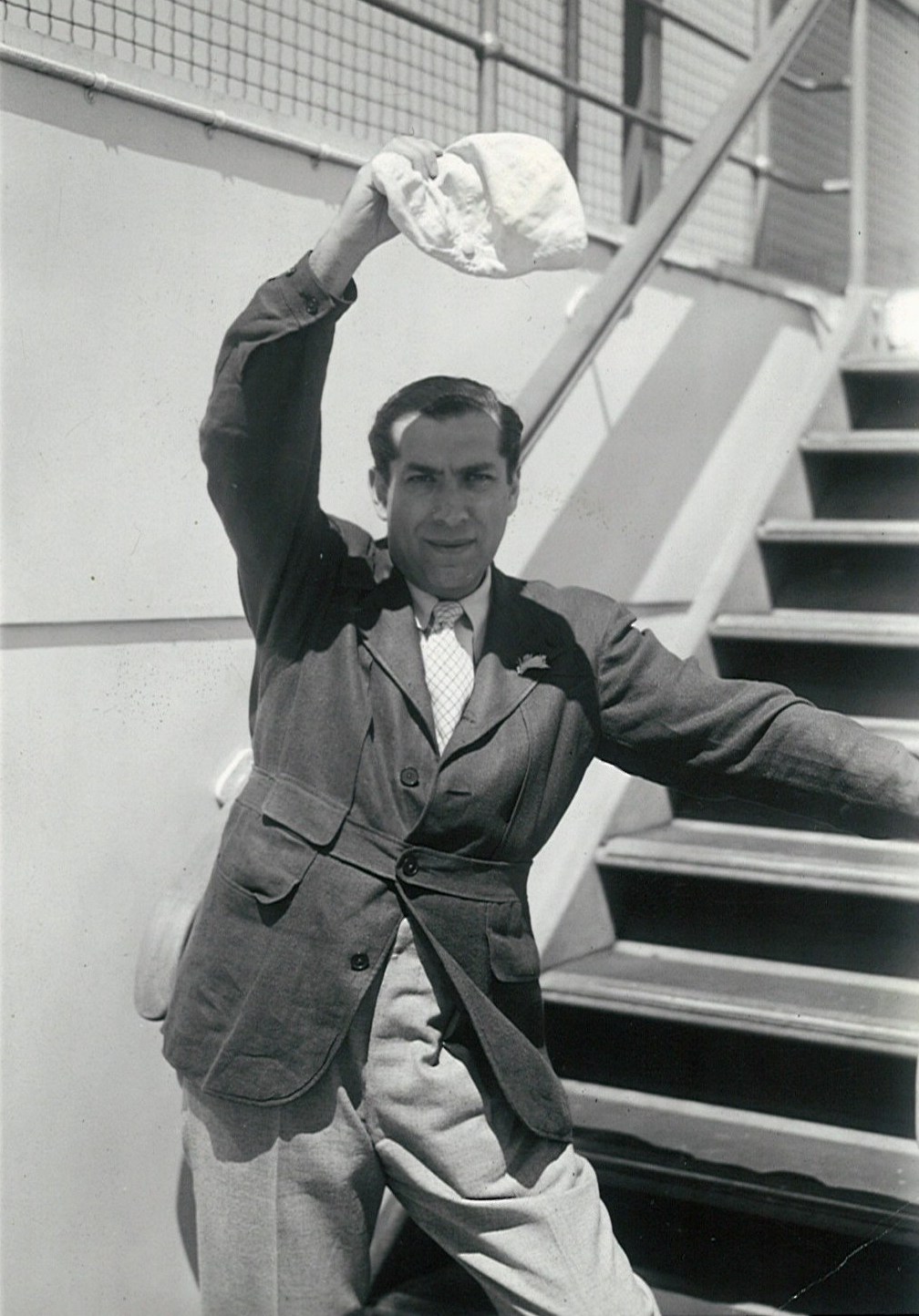

Erik Charell on board a ship to America in the late 1920s, to check out the Broadway competition and to aquire the rights for new songs he could insert into his Berlin shows.

In Swingin’ the Dream he took things to a new level. He put the openly lesbian comedian Moms Mabley in a central role, cracking very “queer” jokes that probably went over the heads of most audience members. But more importantly, half of his 100+ cast was black. And famous. And absolutely central to the story.

When Schwules Museum presented an Erik Charell exhibition in 2010 we, again, featured Swingin’ the Dream. But it didn’t seem to really interest anyone, the rediscovery of Charell’s Im weißen Rössl in its original 1930 jazz version was more relevant, it seems, as was a new look at his other Berlin hits (Casanova and Drei Musketiere).

Poster for the Erik Charell exhibition at the Schwules Museum Berlin, 2010.

A few years later I heard that some people in New York City were interested in bringing Swingin’ the Dream back as a concert. This was even announced officially. I remember corresponding with someone in charge at City Centre and telling him that no scripts or scores or other materials were available via the Charell Estate, handled today by a prominent lawyer Mathias Schwarz in Munich. His father had been a close friend of Charell’s and was executor of the will, when Charell died in Munich in 1974.

Erik Charell’s well-ordered library in his Munich living room, early 1970s. (Photo: Operetta Research Center)

Because the material couldn’t easily be dug up, the concert idea was cancelled. Till it resurfaced now, as a collaborative effort of the Royal Shakespeare Company and Young Vic in the UK, and the Theatre for a New Audience in New York. With support from the Arts Council England they went to work on a reconstruction of Swingin’ the Dream.

On the RSC website we learn: “Swingin’ the Dream was produced by writer and critic Gilbert Seldes and director Erik Charell, and was filled with some of the era’s biggest names in entertainment, both on and off stage. The set designs were based on the cartoons of Walt Disney and the production was one of renowned choreographer Agnes de Mille’s early ventures. The array of performing talent was particularly astonishing […]. It was the music that was the real draw for the show. Charell combined original music by composer Jimmy Van Heusen (who went on to win four Academy Awards during his career) with popular jazz standards, including ‘Ain’t Misbehavin,’ ‘Blue Moon’ and ‘Jeepers Creepers’. One of the musical’s new compositions, ‘Darn That Dream’, became a hit when it was released the following year by Benny Goodman, the “King of Swing”. Goodman joined famed jazz pianists Fats Waller and Count Basie to create the sound for Swingin’ the Dream, which also brought in elements of Felix Mendelssohn’s 1842 version of the play, including his famous Wedding March.”

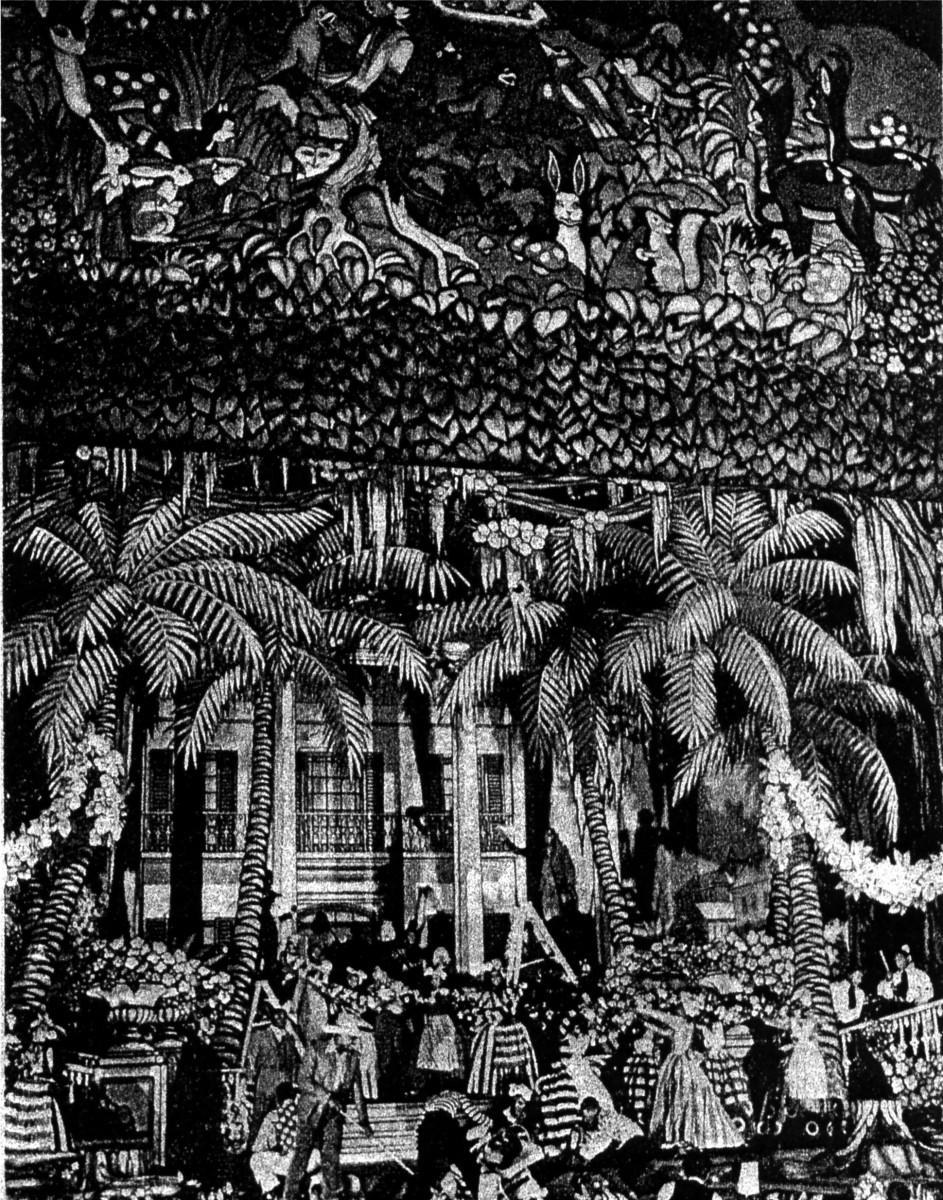

The opening gardening scene from the 1939 “Swingin’ the Dream” production, as seen in the original program. (Photo: Operetta Research Center)

We are also reminded by RSC that “sadly, all complete scripts and footage of the production have now been lost, leaving only scant evidence of what this jazz-infused spectacle was truly like. Even so, Swingin’ the Dream remains widely regarded as one of the most ambitious and intriguing Broadway musical adaptations of Shakespeare to ever take to the stage.”

The first results of the RSC reconstruction efforts were presented in a 55 minute online concert on 9 January, 2021, live from the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Straford-upon-Avon. A small jazz band – with arranger Peter Edwards at the piano himself – accompanied a cast of nine who sang the songs that are known to have been part of the show. While the performers were all sympathetic, positioned on an empty stage in an empty theatre, it took them a while to do something you might call “characteristic” (and convincing) with their material. Which made most of the first half of the concert seem a little underpowered.

The 2021 RSC cast presented “Swingin’ the Dream” as an online concert. (Photo: RSC / Screenshot)

Kemi-Bo Jacobs together with Alfred Clay, Georgia Landers, Andrew French, Cornell S. John, Mogali Masuku, Baker Mukasa and Anne Odeke told the audience about the background of the show and about who played what back in 1939. Which was interesting and would definitely make for a great PBS or BBC documentary! (Or arte, if they could ever be seriously bothered with anything.)

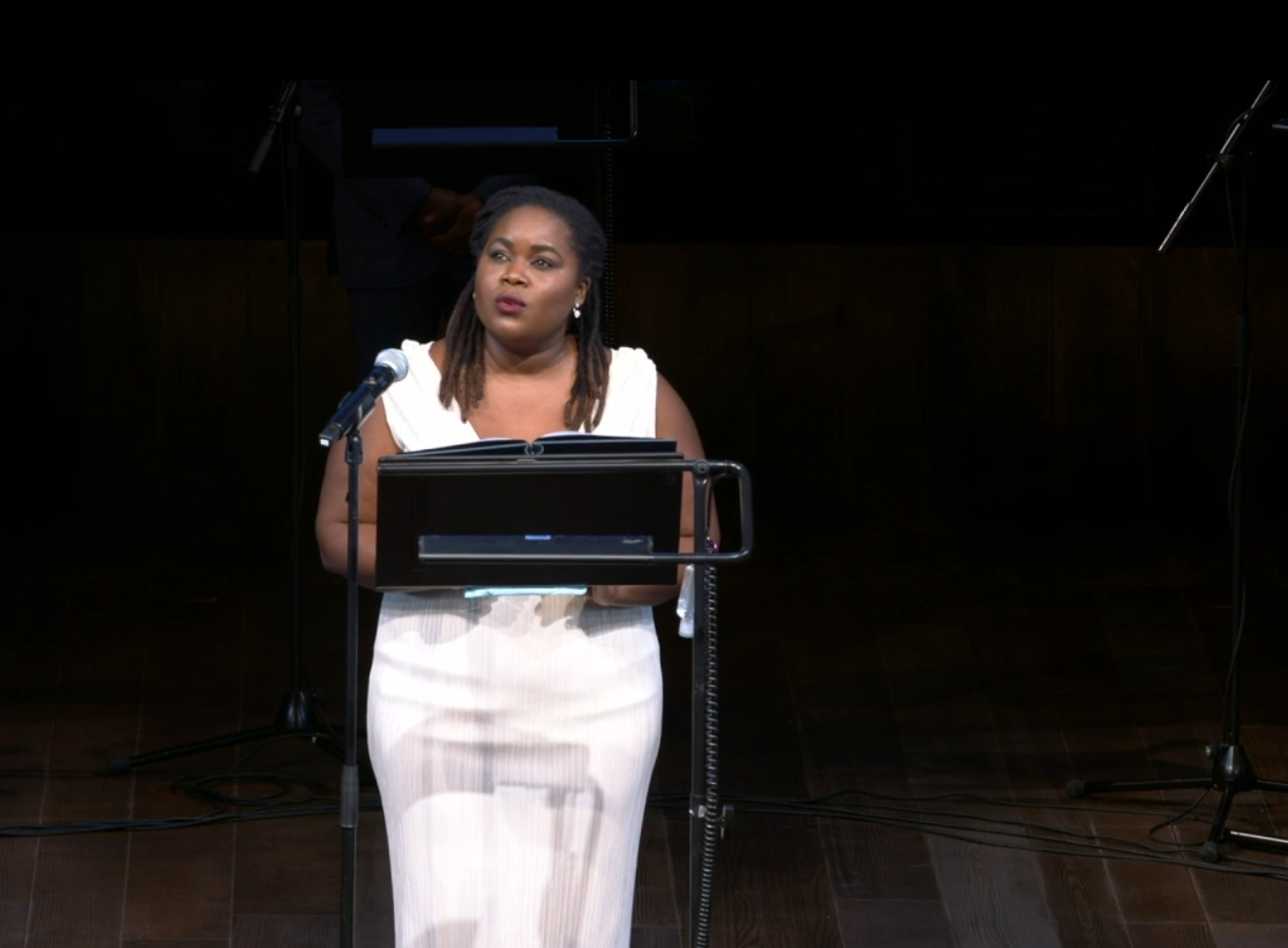

For me the only real musical sensation was Zara McFarlane as Titania, singing the magical song about “Moon Glow” and, of course, the “Darn That Dream” number by Jimmy van Heusen. Which later became a jazz standard, even sung by people like Doris Day and Petula Clark!

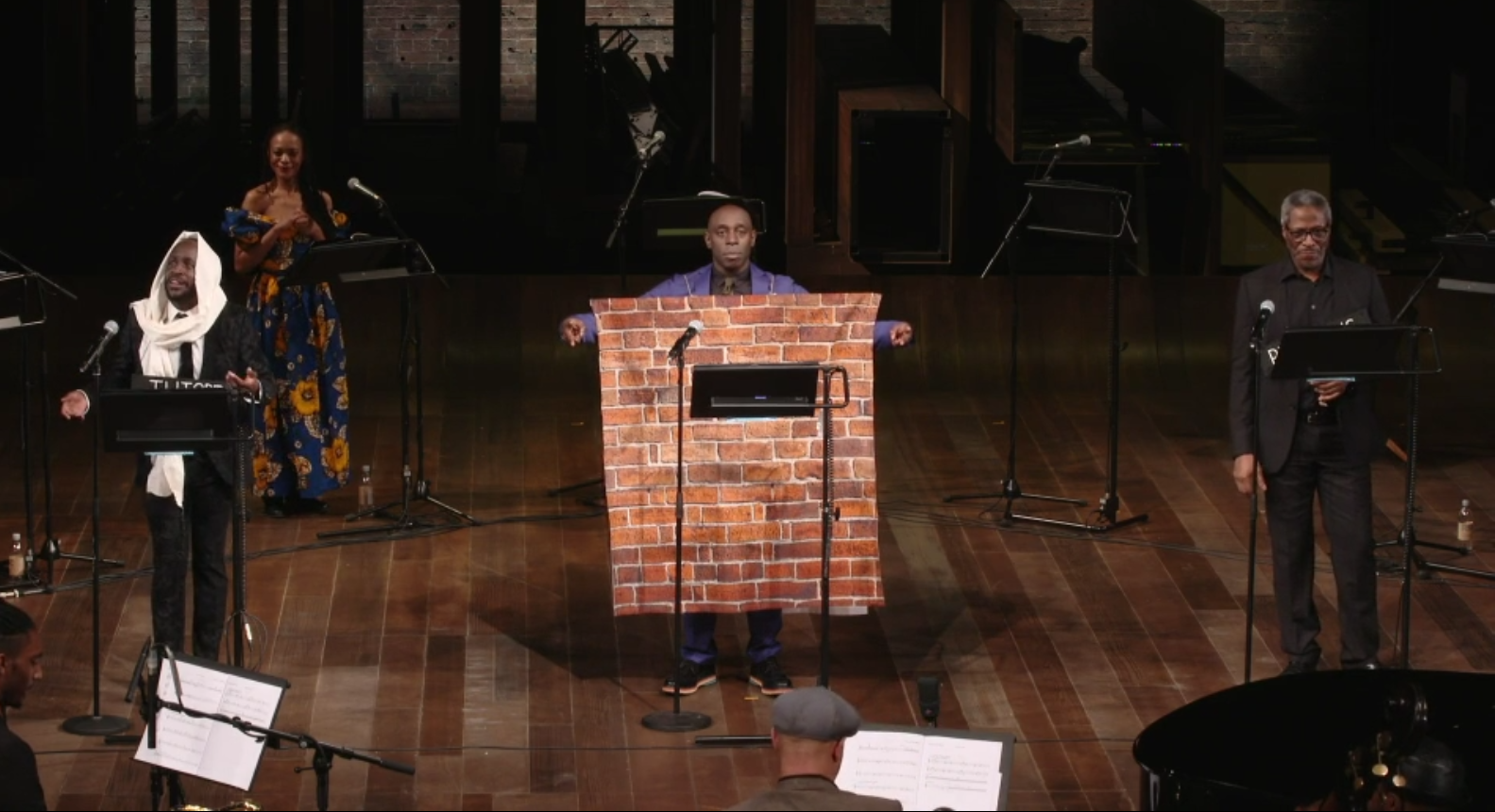

As it turns out, the only surviving manuscript that has been found by RSC is that for the “Pyramus and Thisbe” scene, in which the musical titles used are scribbled on the side of the pages. This scene was presented in full, and it showed just how well the Charell approach to Shakespeare works – with Andrew French playing “The Wall”, plus Cornell S. John as Pyramus opposite Baker Mukasa’s hilarious cross-dressed Thisbe.

The “Pyramus and Thisbe” scene from “Swingin’ the Dream” at the 2021 RSC concert. (Photo: RSC / Screenshot)

An astonishing 1,2 thousand people watched the concert, at 10 pounds an online ticket. In the pre-performance chat dancers from New York greeted Shakespeare scholars from Oxford and musical theater aficionados from Germany. Obviously, there’s a lot of interest in Swingin’t the Dream. What was presented online was hopefully only a first glimpse of many more glories to come.

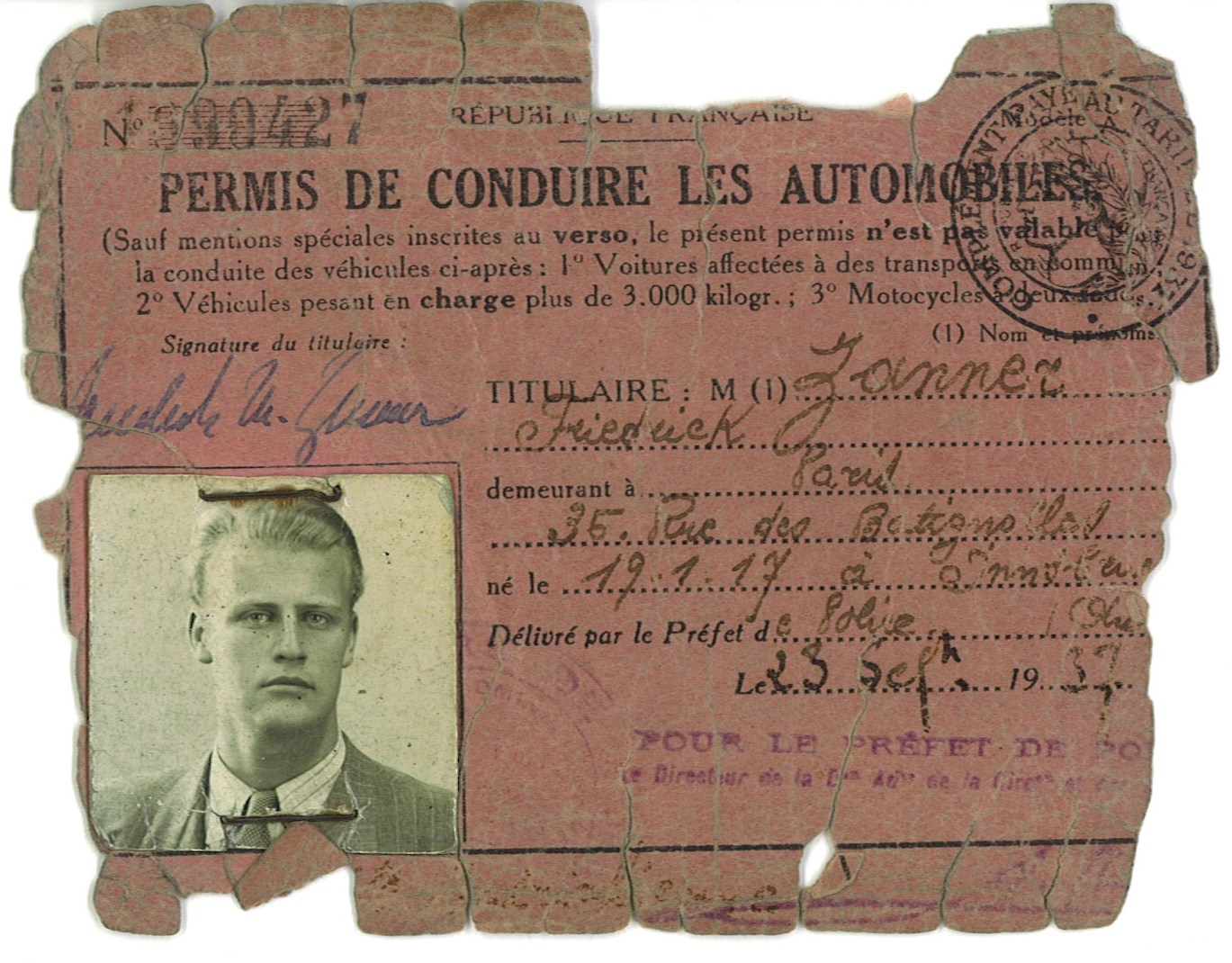

When Charell died in 1974, his friends and heirs took his library apart. I remember the widow of one of his life partners (and heirs), Friedrich Zanner, giving me the Bible Charell had received as an 18 year old in Breslau, at his protestant confirmation (as a Jewish boy). It was in her possession, and she believed I should have it, as a thank you for putting on the exhibition at Schwules Museum and bringing the name Charell back into circulation.

Copy of Friedrich Zanner’s driver’s license, given to the Operetta Research Center by Mr. Zanner’s widow.

If that Bible survived Charell’s departure from Germany in the early 1930s, the years in exile, and the return to Germany, it is unlikely that a man so well organized as Erik Charell would not have saved all of the scripts for his famous shows, flops or not. But no one of his former friends seems to have cared about this – maybe they had no idea what Swingin’ the Dream or any of the other titles was? Maybe they threw the boxes away because they thought them worthless back in the 70s? After all, who knew back then that a jazz version of the Merry Widow might one day be a hot item again?

Maybe the material is still somewhere out there and just needs to be found by the children or grandchildren of those who took home items from Charell’s Munich apartment in 1974?

More of Charell’s library and art collection in his Munich bedroom, early 1970s. (Photo: Operetta Research Center)

Which is why this reconstruction project needs as much visibility and publicity as possible. So those who might know where the scores and scripts are realize what treasure are in their possession, so they might contact the RSC and help reassembling the full show again.

Because Swingin’ the Dream is not just relevant in times of Black Lives Matter. It was a daring show by a gay Jewish man in 1939 who tried to create something novel – and bring some of the liberation he had experienced during the Weimar Republic in 1920s Berlin to Broadway in the late 1930s. He failed spectacularly. But times have changed, and it is worth giving his experiment another chance, by at least knowing what it actually sounded like.

Zara McFarlane as Titania in the 2021 concert of “Swingin’ the Dream.” (Photo: RSC / Screenshot)

You can watch Kwame Kwei-Armah, Artistic Director of the Young Vic in London, Jeffrey Horowitz, Founding Artistic Director of the Theatre for a New Audience in New York, and RSC Artistic Director Gregory Doran, talk about Swingin’ The Dream here.