Kurt Gänzl

The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre

1 September, 2001

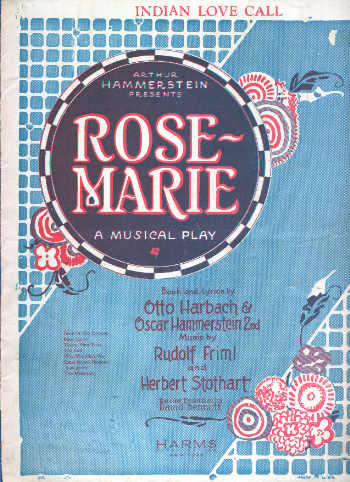

One of the most successful romantic musical plays of the 1920s, Show Boat (Ziegfeld Theater, New York, 27 December 1927) endured into the quasi-sophisticated fin de siècle years much better than librettist Hammerstein’s other memorable successes of the period, Rose Marie and The Desert Song, there to be acclaimed as the masterpiece of the American musical theatre. A large amount of that enduring power has been derived from the show’s very basis, Edna Ferber’s successful novel, the outlines of which Hammerstein and composer Kern followed fairly closely in their construction of the show, whilst eschewing some of its darker and more unpleasant endings.

Original sheet music cover for the 1927 hit “Show Boat.”

Unlike Rose Marie and The Desert Song, the musical play Show Boat – although it held to many of the basic tenets of standard operetta – was not laid out with a traditional cast of predictable romantic comic-opera characters, a soprano and baritone/tenor destined to be mated at the final curtain, a villain thwarted, a couple of soubrets with a romance pursued in parallel to the vocalists’ one, and so forth. Show Boat had no real `villain’, the soprano and baritone were wedded at the end of the first act (and the soubrets in the first interval), the `hero’ — probably the most anti-heroic hero in a major musical since Billee Taylor and Ange Pitou — fell to his own weakness, and the heroine suffered misery that was not just temporarily losing her boyfriend, even if she did, like Sally and her sisters, rise operetta-conventionally in the final reel to join the vast number of musical-play heroines crowding out the star dressing-rooms of Broadway.

It also had two further unconventional elements to its libretto: the genuinely dramatic sub-plot of the mixed-blood actress whose life is ruined by the laws of miscegenation, and the colourful background to the Mississippi scenes provided by a group of negro principals and choristers who were not just mammy-lingoed minstrels and low comic relief.

Cap’n Andy Hawkes (Charles Winninger) and his wife, Parthy Ann (Edna May Oliver), run a show boat on the Mississippi river. Amongst their employees are leading lady Julie La Verne (Helen Morgan) and her husband Steve Baker (Charles Ellis), soubrets Frank Schultz (Sammy White) and Ellie May Chipley (Eva Puck), and negro maid Queenie (Aunt Jemima).

Helen Morgan fainting, in the original stage productions of “Show Boat.” (Photo: Rodgers & Hammerstein Foundation/rnh.com)

Whilst the boat is berthed at Natchez, the exposure of Julie’s mulatto blood forces her and Steve to flee the state and the Hawkes’s daughter Magnolia (Norma Terris) and the handsome riverboat gambler Gaylord Ravenal (Howard Marsh) take their places in the company. Soon the young pair are wed, and leave the river. But Ravenal’s luck as a gambler is intermittent and he is unwilling or unable to find a stabler employ. The good days soon pass, and the gambling husband, knowing himself a burden to his wife and young daughter, finally leaves them. Thanks to an abnegative gesture by Julie, Magnolia finds work and success as a singer in a club and she goes on from there to Broadway fame. In the years that follow, daughter Kim follows her mother’s steps to stardom and Frank and Ellie, too, end up rich and happy, but Julie dwindles to a sad off-stage end. Nothing is heard of Ravenal until one day he runs into Magnolia’s father and is persuaded to return to the show boat, where his wife has taken her retirement, and there on the Mississippi river – where nothing ever changes – 30 years after their first meeting, the pair are reunited in time for the final curtain.

Poster from the 1951 MGM film version of “Show Boat.”

The score which illustrated this tale was very much more substantial musically than the song-and-dance scores which Kern had supplied for the musical comedies of the previous decade. It mixed the tones of comic opera, in the romantic music for the lovers (`Make Believe’, the waltz duet `You Are Love’) and some dashingly insouciant solos for Ravenal (`Where’s the Girl for Me?’, `Till Good Luck Comes My Way’), with the regular soubret brand of numbers for Frank and Ellie (`I Might Fall Back on You’, `Life on the Wicked Stage’) in classic style and added to these a variety of negro-flavoured pieces from a beautiful baritone hymn to the Mississippi, `Ol’ Man River’, sung by Queenie’s shiftless man, Joe (Jules Bledsoe), to a searing ballyhoo (`C’mon Folks’) and the superb ensemble `Can’t Help Lovin’ That Man’. This all in the first act.

The second, rather in the style of the old variety musicals, rather tailed away in so far as important new songs were concerned. It consisted principally of a number of acts, some of which used Kern’s own material, others of which (in the manner which he had shown himself effectively willing to use in earlier shows) he selected from the successes of an earlier period, the period in which the show was set. Amongst these were Charles K Harris’s A Trip to Chinatown hit, ‘After the Ball’, performed by Magnolia as her nervous club début, and Joe Howard’s infectious `Goodbye, My Lady Love’, given as an item by Frank and Ellie. Julie’s stand-up song, however, was an older number by Kern himself which he had been unsuccessfully trying to place in a show for some time. `Bill’ found itself a home worth waiting for in the second act of Show Boat. The other `variety’ items included a variable selection illustrating the entertainment at the World’s Fair, several dances, and a series of impersonations performed by Miss Terris in the character of Kim. Apart from `Bill’, only the jaunty `Why Do I Love You?’ and Queenie’s `Hey, Feller!’ added to the list of new Kern numbers in the show’s second half.

Show Boat was produced by Florenz Ziegfeld. It had a false start when, with leading players Elizabeth Hines (Magnolia), Guy Robertson (Ravenal) and Paul Robeson (Joe) announced, it had to be postponed to allow its authors more time to complete their work, but it ultimately opened (without those three players), directed by Hammerstein, at Washington’s National Theater on 15 November 1927. It was instantly successful, but there were nevertheless alterations made in the half-dozen weeks prior to the Broadway opening. Several pieces of music were removed and `Why Do I Love You?’ was added.

The Broadway opening confirmed the out-of-town reception and the production went on to play 575 performances on its first New York run.

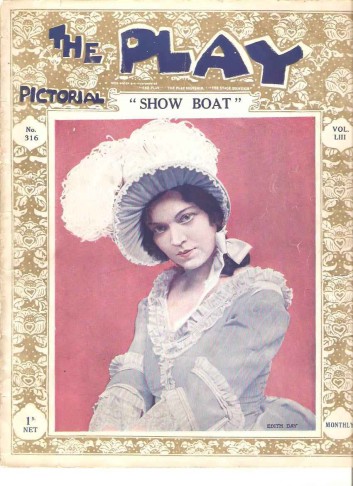

The playbill for the original London production of “Show Boat.”

London’s production, under the management of Alfred Butt and the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, starred Edith Day (Magnolia), Howett Worster (Ravenal), Marie Burke (Julie), Leslie Sarony (Frank), Dorothy Lena (Ellie), Cedric Hardwicke (Hawkes) and Paul Robeson in the rôle of Joe for which he had been originally slated. In spite of the difficulties engendered by the mixed-race cast (blacks and whites had to dress on opposite sides of the stage, Robeson not excepted) it had a good run of 350 performances. Australia’s J C Williamson production of Show Boat also had a good, if unexceptional, run. Glen Dale (Ravenal), Gwynneth Lascelles (Magnolia), Muriel Greel (Julie), Bertha Belmore (Parthy Ann), Leo Franklyn (Frank), Frederick Bentley (Andy), Madge Aubrey (Ellie) and the blacked-up Colin Crane (Joe) and June Mills (Queenie) played 80 nights in Melbourne and rather less in Sydney (Her Majesty’s Theatre, 2 November 1929). This was, however,a better record than the disappointing 115 nights achieved by a French adaptation (ad Alexandre Fontanes, Lucien Boyer) mounted by Fontanes and Maurice Lehmann in the vastness of the Théâtre du Châtelet with British soprano Desirée Ellinger as Magnolia and American baritone Harvey White cast as Joe alongside locals Bourdeaux (Ravenal) and Jacqueline Morrin (Julie).

Cover of the original piano score.

If Show Boat did not follow Rose Marie further into Europe, it nevertheless established itself firmly at home. In spite of the iffy financial conditions of the early 1930s, it was toured, filmed in 1929, and brought back to Broadway at the Casino Theater (19 May 1932) with Dennis King (Ravenal) and Robeson alongside Misses Terris and Morgan and Winninger (180 performances) prior to another tour and a second film, with Winninger, Robeson and Miss Morgan featured alongside Irene Dunne (Magnolia) and Allan Jones (Ravenal). London reprised the show during the Second World War (Stoll Theater, 17 April 1943, 264 performances) with a cast headed by Gwynneth Lascelles (Magnolia), Bruce Carfax (Ravenal), Pat Taylor (Julie), Leslie and Sylvia Kellaway (Frank, Ellie) and blacked-up basso Malcolm McEachern (Joe), and three years later it again played Broadway’s Ziegfeld Theater (5 January 1946, 418 performances) with Jan Clayton (Magnolia), Charles Fredericks (Ravenal) and Carol Bruce (Julie) and toured yet again.

In 1951 a third film version (Kathryn Grayson, Howard Keel, Ava Gardner, Joe E Brown, Marge and Gower Champion, William Warfield) made its way to the screen.

In 1954 the show was taken into the New York City Opera, in 1970 it made its first appearance on the German-language stage, and in 1971 had its longest-running production to date, in London. Harold Fielding’s mounting (29 July) starred Frenchman André Jobin (Ravenal) alongside Americans Lorna Dallas (Magnolia), Thomas Carey (Joe) and Kenneth Nelson (Frank) and locals Cleo Laine (Julie) and Jan Hunt (Ellie) and played 910 performances at the Adelphi Theatre.

In 1990, on the heels of the issue of a major EMI recording – and with the black casting which had originally been such a problem now a grand and politically correct plus – it appeared once more in Britain and in London (London Palladium 25 July) in a production sponsored by Opera North and the Royal Shakespeare Company (but including barely a member of either company) and featuring Karla Burns (Queenie) and Bruce Hubbard (Joe) of the recording’s cast.

And in 1994 a fiddled-even-further-than-usual with version (which programme-noted that it was a combination of three stage versions and one of the films, but included alterations not noticeable in any of them) was brought from Canada to Broadway (Gershwin Theater, 2 October). Mark Jacoby (Ravenal), Rebecca Luker (Magnolia) and John McMartin (Andy) featured, and the revival totted up a healthy run of 949 performances, followed by a fresh tour, and got showings in both Australia where the production opened the new Lyric Theatre (7 April 1998), with Peter Couzens, Marina Prior and Barry Otto featured and Nancye Hayes as Parthy to less than impressive effect, and in Britain (Prince Edward Theatre, 20 April 1998) where a ‘Broadway cast of 57’ was boasted on ads that billed director Hal Prince large … but never mentioned Hammerstein or Kern. And most of the audience were unaware they were watching a Cibberized classic.

Show Boat has become widely accepted and promoted as the foremost American romantic musical-theatre work of its period. In the modern English-speaking world (if not elsewhere) it is today surely the most performed. It has had an entire book devoted to it, American (and even other) commentators write of it with awe and never a pejorative adjective, even if American (and other) producers and directors nevertheless see fit endlessly to fiddle with and ‘improve’ it.

There is little question that its canonization is at least in part justified, and that there is nothing (give or take a bit of a sag late in Act 2) to be pejorative about.

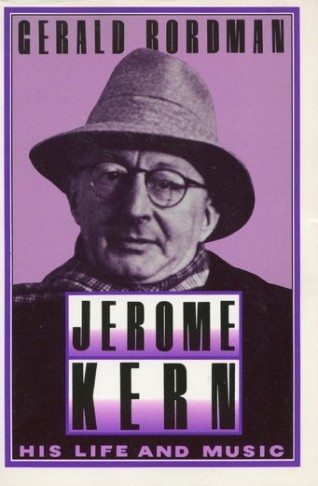

Gerald Bordman’s Jerome Kern biography,

There is, however, less justification for investing the show with `significance’. Certainly it has more breadth, depth and verisimilitude in its storyline and even its characters than a Rose Marie or even a Desert Song, but these qualities were not innovations. In the same way, its avoidance of many of the more popular operettic clichés of its era is a quality, but those clichés had been avoided many times before, by those who had wanted (and most didn’t) to avoid them. Bordman (Jerome Kern, His Life and Music, OUP) calls the show `the first truly, totally American operetta … identifiable American types sang American sentiments in an American musical idiom’. There is no question over any word there except `first’ and, even then, the `truly’, the `totally’ and the `operetta’ narrow the field, but something like the same comments could surely have been applied in their time to such older period American musical plays as Naughty Marietta, The Mocking Bird or the Civil War piece Johnny Comes Marching Home, in spite of the Irish, German and English blood in the pedigree of their writers. Show Boat stood (and stands) out among the best of the romantic musicals of the later 1920s and 1930s not because it was innovatory (for a poor show may be innovatory), but because it was excellent, with the kind of excellence which endures.

UK: Theatre Royal, Drury Lane 3 May 1928; France: Théâtre du Châtelet Mississippi 15 March 1929; Australia: Her Majesty’s Theatre, Melbourne 3 August 1929; Germany: Städtische Bühne, Freiburg 31 October 1970; Theater des Westens 10 October 1979; Austria: Volksoper 1 March 1971

Recordings: complete (EMI, 3 records London cast recordings (WRC), 1946 revival (Columbia), 1966 revival (RCA), London revival (Stanyan), 1994 Toronto revival (Quality), film soundtrack ASI (CBS/MGM), selections (TER, Columbia, RCA Victor, HMV, Decca), selection in Swedish etc

Literature: Kreuger, M: Show Boat: The Story of a Classic American Musical (OUP, New York, 1977)

; ;