Harry Forbes

Operetta Research Center

5 June, 2021

Paul Abrahám’s flavorsome jazz operetta, which premiered to great acclaim in 1932 Berlin at Großes Schauspielhaus, only to have its run cut short by the Nazis, as a result of Abrahám and several of the leads’ Jewish heritage, receives its first – and very welcome – complete recording courtesy of Naxos and the Chicago Folks Operetta.

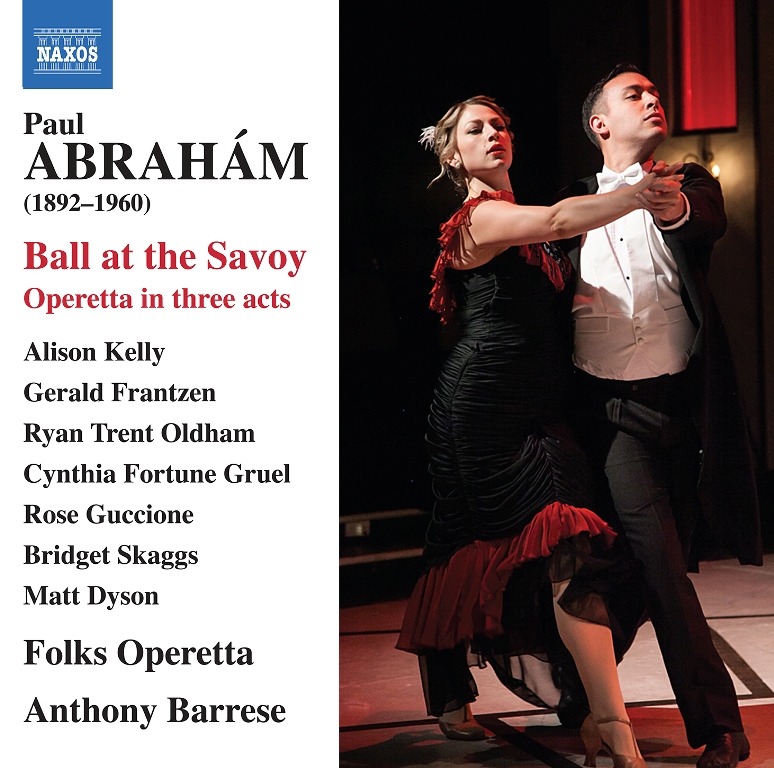

The cover of the 2014 recording of Ábrahám’s “Ball at the Savoy” with the forces of Chicago Folks Operetta. (Photo: Naxos)

Librettists Fritz Löhner-Beda and Alfred Grünwald fashioned a story not unlike that of Die Fledermaus wherein a wife goes to the titular ball at the Savoy Hotel in Nice in disguise to spy on her philandering husband, though in this version she endeavors not to flirt with her clueless husband, but rather enjoy a vengeful sexual encounter of her own. (To read more about the plot, click here.)

The central couple, Aristide, the Marquis de Faublas, and his wife Madeleine (originated by the incomparable Gitta Alpár) are played here by real life couple Gerald Frantzen and Alison Kelly, respectively artistic director and executive director and co-founders of the Chicago Folks Operetta. (In 2013, Naxos issued a similarly complete recording of Leo Fall’s The Rose of Stambul.)

Gerald Frantzen as Aristide in “Ball at the Savoy.” (Photo: Chicago Folks Operetta)

Chicago Folks Operetta’s 2014 production (briefly streamed last year at the start of the pandemic lockdown) followed on the heels of a 2010 WDR radio broadcast with the Cologne Philharmonic conducted by Eckehard Stier, arranged from the original manuscript by Henning Hagedorn and Matthias Grimminger. That, in turn, led to a memorable 2013 mounting by Berlin’s Komische Oper, directed by Barrie Kosky, which was streamed internationally the following year. It had truly groundbreaking performances by star actress Dagmar Manzel as Madeleine (with a raspy deep chanson voice instead of Alpár’s high flying coloratura) and an equally show stopping star turn by Katharine Mehrling as Madeleine’s best friend Daisy – a female American jazz composer. Add to that Helmuth Baumann, who created the role of Zaza in La Cage aux Folles in Germany in the 1980s as Mustafa Bey, the male comedian in the story, Adam Benzwi conducting, plus Otto Pichler’s beyond-sexy dancers doing “anal clap dances,” and you have the ingredients for a hit that ran for many seasons at Komische Oper, almost always sold out.

Recording wise, apart from the peerless highlights from the original Berlin production, and a much-altered 1935 film version with Alpár in the lead, we’ve only had recordings of individual songs, and far fewer of those for that matter than from Abrahám’s more enduring works, Viktoria und ihr Husar (1930) and Die Blume von Hawaii (1931). So the present release is all the more welcome, especially since it’s the first big modern Ábrahám recording in English.

Folks Operetta’s Musical Director Anthony Barrese leads his forces in a spirited reduction of the aforementioned orchestrations. There are 18 players in the orchestra, but the sound is satisfyingly full-bodied, and they handle the romantic pieces, the dramatic finales, and the wonderfully infectious jazzy numbers (the unique feature of Abrahám’s works) very well indeed. Better than most German conductors, as a matter of fact, who have no knowledge and even lesser experience with typical Broadway style dance numbers.

It can’t be said that the cast captures the European flavor of this most Continental of works. The line readings are, on the whole, serviceable, and the full dialogue on the recording allows us to hear all the music in its appropriate context. Because the story matters, and it is fascinating on so many levels, as a tale of female emancipation, as a marriage farce, as the story of a woman composer, as the taming of a Turkish macho etc.

At times, I couldn’t help thinking the mostly uninflected American accents heard on the new recording would be suited to one of Jerome Kern’s Princess Theater shows too. The non-operatic approach strongly distinguishes this recording from the operetta offerings in the cpo series, usually based on productions from the Ischl operetta festival or concert performances of the Bayerischer Rundfunk in Munich.

Cynthia Fortune Gruel as Daisy in “Ball at the Savoy.” (Photo: Chicago Folks Operetta)

Vocally, everyone here is adequate, sometimes more than that. Cynthia Fortune Gruel as Daisy Darlington, and Ryan Trent Oldham as the much-married Mustafa Bey have the liveliest, jazziest numbers (“Kangaroo,” “Mister Brown and Lady Claire,” “Out on the Town,” “The Niagara Fox,” “At Home along the Bosporus,”and “Take a Trip to Alma-ata,” “Why Am I In Love With You?”) and threaten to steal the proceedings just as Rosy Barsony and Oskar Dénes did in 1932. And I’d venture to bet any of these numbers could bring down the house if done on Broadway today.

Both Barsony and Dénes, incidentally, were able to reprise their roles in the 1933 London production at Drury Lane adapted and translated by Oscar Hammerstein II, ten years before he joined forces with Richard Rodgers for Oklahoma!

The Hammerstein version very much tones down the sexual rollicking of the Berlin original – in terms of explicitness in the lyrics and details of the action – so it’s probably a good idea that the Chicago version sticks closely to Löhner-Beda and Grünwald instead of the Hammerstein re-write, even if his name would have stirred more interest in the USA from popular musical theater enthusiasts. So, while it would be fascinating to hear a reconstruction of that London version, Glagov and Frantzen’s translations are skillful, and often clever. (The extensive highlight recordings from London have sadly never been released on CD, though the explosive orchestral playing and stunning casting would make a re-release very welcome.)

On the new disc, Bridget Skaggs has some bright moments as Tangolito, the femme fatale who was Aristide’s former flame, and holds him to a long-ago IOU to have dinner with her whenever she asks for it, thereby setting the plot in motion. She gets to sing one of the show’s breakout hits, the catchy “Bella Tangolita.”

Alison Kelly and Rose Guccione in “Ball at the Savoy.” (Photo: Chicago Folks Operetta)

Kelly’s version of the show’s other big takeaway tune, “Toujours, L’amour” is nicely done, if not with Alpár’s intoxicating vocal allure. And she does well with the opening paean to “Sevilla” (in tandem with Frantzen), her exuberant description of her “Wedding Night” (with Gruell), and a couple of other touching pieces. She has fun with an amusing Russian accent in her ball disguise. Even so, I’ve heard that Dagmar Manzel earned extra applause in almost every performance in that scene, the sort of bravura performing style missing in Chicago. And when you listen to Alpár…

Recording quality is fine, though the orchestra never sounds as opulent or overwhelming as what Adam Benzwi offered in Berlin – but Komische Oper never managed a recording (only a radio broadcast that was acoustically marred by bad microphone placement). The music nevertheless registers as satisfyingly full-bodied here, and the dialogue is cleanly captured. There’s a detailed synopsis and informative essay by Glagov. A full libretto can be accessed on the Naxos website.

Ryan Trent Oldham, Alison Kelly and Kingsley Day doing the “Take a Trip to Alma-ata” number in “Ball at the Savoy.” (Photo: Chicago Folks Operetta)

The German language productions – including a star studded staging at the opera house in Nuremberg with Geschwister Pfister, and smaller scale attempts in Halle (East-Germany) and Lübeck (North-Germany) – were, perforce, the more characterful with regard to certain aspects of the cast but until one or any of them are issued commercially, Naxos is the only way to go to hear this wonderful score. The present recording’s fresh and committed cast and accomplished musicianship makes it more than a stopgap.

And, of course, the English language translation will be a boon to non-German speakers, making it possible for the first time since the Ábrahám revival has been set in motion in Germany to understand what the fuss is all about.

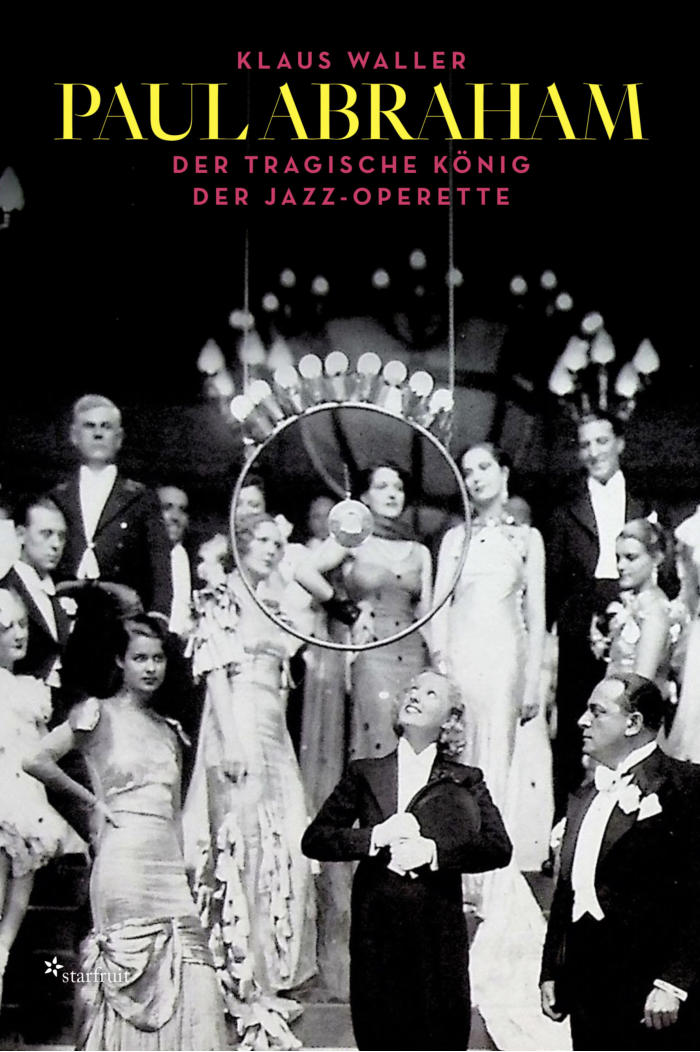

The updated edition of Klaus Waller’s Abraham biography.

By the way, a impressively illustrated new version of Klaus Waller’s Ábrahám biography will also be out soon.