Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

22 November, 2016

In variation of the famous saying “Every country has the government it deserves” – by 18th century political philosopher Joseph-Marie Comte de Maistre – you could argue that every country also gets the operetta it deserves. And it seems, right now, that the differences between countries and operetta performance traditions could not be greater. Some important impulses for change and innovation have recently come from Germany, or to be more precise: from Berlin. And they are now in a direct battle with older ideologies, and opposing international trends.

Andreja Schneider as the moon goddess in Paul Lincke’s “Frau Luna” at the Tipi Zelt am Kanzleramt, Berlin. (Photo: Barbara Braun)

The Germans have a long and complicated relationship with operetta. One of the turning points and the beginning of a new operetta era was the publication of Volker Klotz’s study Operette: Porträt und Handbuch einer unerhörten Kunst in 1991. Brilliantly written, Professor Klotz argued back then that there are “good” and “bad” operettas, and that the “good” shows which represent Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité deserve to be performed and analyzed, most importantley the “subversive” Offenbach pieces, while the fluffy nostalgic and reactionary “bad” shows from Schwarzwaldmädel to Im weißen Rössl should be shoved down the drain: because Mr. Klotz refused to see any irony, wit and humor in them. For decades afterwards, people working in theaters believed every word Mr. Klotz wrote as if it were God speaking to them through Moses or Mohammed, and they followed his orders rigorously. Never questioning his verdicts and rarely bothering to come up with evaluations of their own. It took years for new perspectives to break through and attract a different audience – that might (intellectually) enjoy the shows Mr. Klotz had banned from discourse: jazz operettas and revue operettas among them, not to mention all musicals or Broadway related operettas!

Cover of the 2016 edition of Volker Klotz’s “Operette.” (Studio Verlag)

The major new force, that turned around this cut-in-stone Klotz-based operetta ideology, was Barrie Kosky at the Komische Oper who not only chose jazz and revue operettas for his theater but also demonstrated – with rare Emmerich Kalman and Oscar Straus shows such as Arizona Lady and Eine Frau, die weiß was sie will – that the right casting and staging with dance and color and lights can make long-ignored and supposedly “inferior” shows contemporary, relevant and wonderfully entertaining for younger audience members who wondered why these operettas hadn’t been performed much earlier. And older operetta fans who grew up with the Klotz ideology, finally broke free and admitted their enjoyment of all these resurrected “bad” titles. Notwithstanding the fact that famous academic publisher Bärenreiter re-published the Klotz book in a big, impressive new (and updated) edition simultaneously.

Dagmar Manzel and her male co-stars of “Die Perlen der Kleopatra,” coming to the Komische Oper Berlin in December 2016. (Photo: Jan Windszus Photography)

Now, this out-of-print edition is back once more in a hard-back version published by Studio Verlag, with financial support from the Österreichische Musikzeitung (ÖMZ) who – you will remember – had a somewhat questionable operetta special of their own, recently. The publication of this latest, fourth edition, of the Klotz “bible” coincides with the ground-breaking Frau Luna production at the Tipi Zelt am Kanzleramt, and with the upcoming Die Perlen der Cleopatra at the Komische Oper, to be directly followed by Kalman’s 1945 Broadway operetta Marinka, also at the Komische.

The cast of “Frau Luna” at the Tipi, Berlin. On their way to the moon. (Photo: Barbara Braun)

When you read the basically positive review of Frau Luna in der LGBT magazine Siegessäule, written by Eckhard Weber, you notice the shadow of Volker Klotz still heavily hanging over everything immediately. Before Mr. Weber can say that he actually loved the high camp performance, glittery production and superlative cast, he bashes Paul Lincke’s operetta as “provincial” (“Mollen-Provinzialismus”) and “petty bourgeois” (“kleinbürgerlich”). Without naming him, this is Mr. Klotz forever standing in the way of enjoyment of anything that’s too obviously entertaining (or queer). Because as good Protestants in Germany know: entertainment in itself is sinful and bad. That a group of gender-bending performers beg to differ and pull off their own alternative approach to operetta is refreshing. That this version is a sell-out hit with tourists who are not all “queer” is something that can be called positive in times of political turmoil regarding “gender craze” and homophobic chanting at mass demonstrations in Germany.

Gustav Peter Wöhler (l.) and Andreja Schneider in “Frau Luna”, act 2. (Photo: Barbara Braun)

But obviously, some German critics still have a problem with operetta that goes off too far from the prescribed Klotz path: in the magazine zitty, Friedhelm Teicke lamented that the march music Lincke composed for late 19th century audiences made him think of the Nazis invading Poland. Why exactly the decidedly anti-military production by Bernd Mottl and musical arrangement by Johannes Roloff would make anyone think of Nazis, let alone WW2 and the Invasion of Poland, is beyond me. But at least it puts operetta in the context of political debates that are more interesting than the long held belief that operetta is apolitical nonsense undeserving of critical reflection. Maybe a hyper-critical opinion such as Mr. Teicke’s is better than nothing at all?

Benedikt Eichhorn and Andreja Schneider in their seduction scene, in “Frau Luna” at the Tipi, Berlin. (Photo: Barbara Braun)

While Frau Luna at Tipi proves that it is possible to play operetta commercially in Berlin – with six performances a week – the Komische Oper invests its large state subsidy in larger productions: large in the sense that there is chorus, full orchestra, ballet and everything that’s difficult to finance if you have to look for sponsors for every single costume. (As the Tipi did, remarkably well.)

To put on Perlen der Cleopatra – as a kinky sex farce set in Ancient Egypt – makes for a kind of Oscar Straus series that revives a composer who is mostly reduced to his big hit: Ein Walzertraum. Barrie Kosky managed to avoid Walzertraum altogether, he did not even bother with the Klotz approved Lustigen Nibelungen, but went straight for something else. And to put on 13 (!) performances of Cleopatra – a show once written for Fritzi Massary – demonstrates a deep trust in the pulling power of these titles, and the pulling power of stars such as Dagmar Manzel and conductor Adam Benzwi. Together they will rock the place, there is little doubt about that. Johannes Dunz and Peter Bording are also part of the Cleopatra team.

The desire of modern audiences to discover something new is also taken into consideration with Marinka, a show that Volker Klotz doesn’t even mention in his Operette book, not even in the updated fourth edition. For him, anything that can be linked to “commercial” Broadway is evil and undeserving. That most operettas from Offenbach onwards were written for commercial venues and not for a subsidy theater system, as introduced on a large scale by the Nazis after 1933, doesn’t seem to bother Mr. Klotz. It’s not even part of his pro and contra arguments. But maybe that is typical for a man born in 1930 and brought up with pre- and post-WW2 ideals?

Ades Zabel (l.) and Fausto Israel as alternative casts for the role of the “Moon Groom” in “Frau Luna” at the Tipi, Berlin. (Photo: Barbara Braun)

With the triple treat Frau Luna, Perlen der Cleopatra, and Marinka, Berlin offers a unique opportunity for travelling operetta fans to experience something special in December. Which is probably why many US and UK operetta aficionados have already booked themselves onto the next flight to the German capital.

The Berlin operetta offerings reflect, in a way, the new political leadership of the city which was formed after the election in September 2016: the new red-red-green collation (SPD, Gründe/Bündnis 90, Die Linke) has announced that Berlin should be an a “rainbow city” and that influences the operetta offerings, because all three titles – whether Lincke, Kalman or Straus – are certainly given a rainbow treatment, on a grand scale for a grand audience. Such “rainbow issues” are still – along with any discussion of sexuality – entirely absent from Volker Klotz’s re-published book. And he has also refused to discuss this, or any other issues, with the Operetta Research Center. So we will never know what the grand old man thinks about the developments in the German language operetta world since the first publication of his book in the 1990s, or about the international developments.

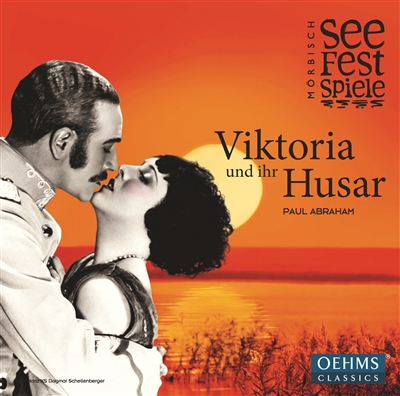

What is sad is that this latest edition of the Klotz book is – again – in German, rather than in English. Because the highly personal interpretations of various Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité shows should be known to English speaking researchers, they are a strong contrast to Richard Traubner’s old operetta book, but also to Kurt Gänzl’s various publications. It seems that the Anglo-American operetta world rarely takes notice of what is going on in terms of research in Germany (and vice versa). But then again, the Austrians – who speak German – don’t take much notice of it either and continue playing operettas their way, too. Which, interestingly, brings the Volksoper Wien closer to Wooster, Ohio than Berlin. (Exceptions always prove the rule.) And when Dagmar Schellenberger joined the new flow and put on Abraham’s Viktoria und ihr Husar at her Mörbisch Festival, the Austrian critics were vehemently opposed to this “degenerate” 1930 jazz operetta – and Miss Schellenberger lost her job. (See archive.)

The cover for the 2016 cast album “Viktoria und ihr Husar” from the Mörbisch festival. (OEHMS Classics)

It’s the way of the world, you might say. And the world has a lot of very diverse operetta on offer right now: whether it’s the Budapest Operetta Theater resurrecting little known Hungarian titles in their own glitzy way (e.g. Kalman’s Duchess of Chicago or Viktor Jacobi’s Sybill), or England staging all-male Gilbert & Sullivans, rare Offenbach, or rediscovered Franz von Suppé shows like A Trip to Africa, the latter coming up now in December. Add to this the USA with their more restrained – anti-daring – stagings of Victor Herbert in New York or various gems in Ohio. There’s a lot to chose from, and to finish with another famous saying: “competition is good for business.” It will be interesting to see whether any of these national trends can inspire one another in the future and whether a real international exchange of ideas (and audiences) will be possible.

“Die Herzogin von Chicago” at the Budapest Operetta Theater. (Photo: Budapesti Operettszínház)

If you stay tuned, we’ll have reviews of the latest Berlin shows, written by UK and US authors from their respective perspectives, soon. (For John Goves’s article, click here.)

Ich weiß nicht, ob schon mal irgendwo deutlich geschrieben wurde, auf welche Art Klotz in seinem Buch arbeitet (die aktuelle Ausgabe kenne ich leider noch nicht):

Zunächst denkt er sich das Konzept »Offenbachiade« aus (von dem heute bekannt ist, das es nichts mit Offenbach zu tun hat) und legt es als Messlatte an alle anderen Operetten an: Offenbachiade=gut, alles andere=schlecht.

Ob eine Operette diesen Kriterien entspricht oder nicht, wird von ihm zunächst vollkommen willkürlich (ich vermute nach persönlichen Vorlieben) festgelegt. Darauf wird das entsprechende Werk aufgrund dieser Festlegung »analysiert« – das Ergebniss dieser »Analyse« steht also schon von Anfang an fest. Wissenschaftliches Arbeiten sollte so eigentlich nicht aussehen…

Seine hanbüchenen Ausführungen zum Musical, sind ja allegemein bekannt und bestechen durch ziemlich fehlende Sachkenntniss. Ich habe beim Lesen seines Buches außerdem öfter den Eindruck, dass Klotz Probleme damit hat, aus Klavierauszügen zu einem Klangeindruck zu erlangen. (Manchmal scheint er eher Auffühungen der 70er Jahre zu beschreiben als das, was sich im Notenmaterial findet.)

Das stört aber nicht: So verweist er z. B. auf einen direkten Bezug auf »Heil dir im Siegerkranz« in der »Recken von Alt-Burgund«-Hymne in den »lustigen Nibelungen«. In der Realität haben beiden Stücke weder in Text noch Musik irgendwelche Ähnlichkeiten. Aber das ist für Klotz gerade der Beweis, denn so sind sie »in der Negation miteinander verbunden« (aus dem Kopf zitiert). Ob Klotz für diese Methode, mit der man einfach alles »wisschenschaftlich« erklären kann, einmal recht gewürdigt wird?