Kevin Clarke

Operetta Research Center

19 August, 2023

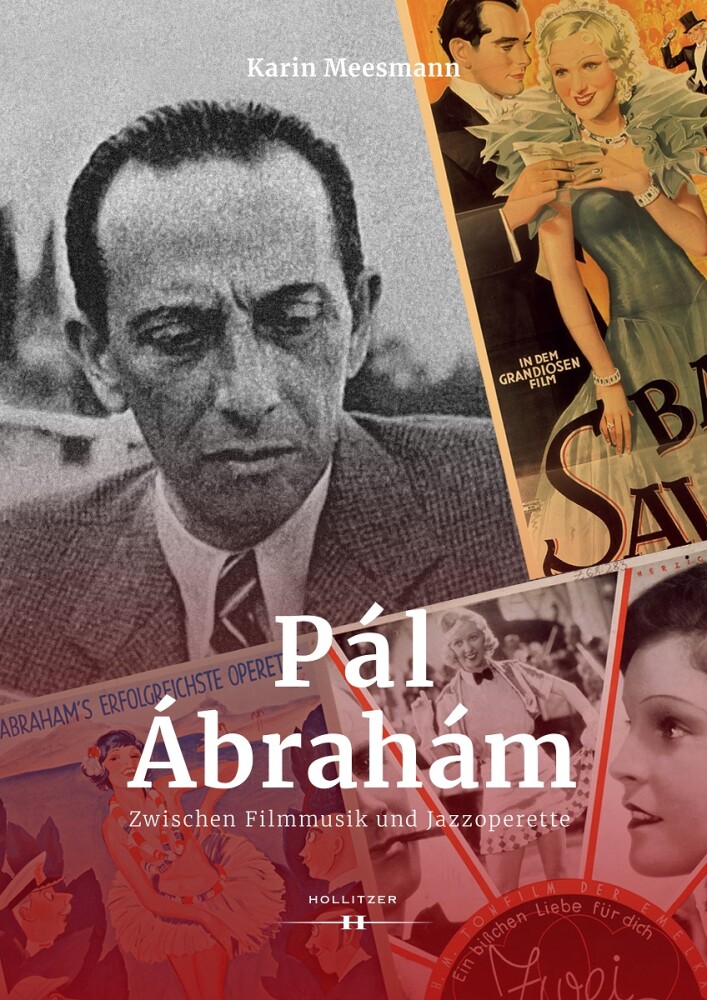

Anyone interested in Paul Ábrahám will have known – or will have heard – that Karin Meesmann has been working on a monumental biography that wanted to set various matters straight. This project has been much talked about endlessly, but its finalization (and publication) has been postponed many times over, reaching a point where it almost became a joke to say “It’s supposed to come out in … [fill in the gap]”. But now it is actually here, a 500+ page tomb of information, lavishly illustrated and packed in XL catalogue format. The title: Pál Ábrahám: Zwischen Filmmusik und Jazzoperette.

Karin Meesmann’s “Pál Ábrahám: Zwischen Filmmusik und Jazzoperette”. (Photo: Hollitzer)

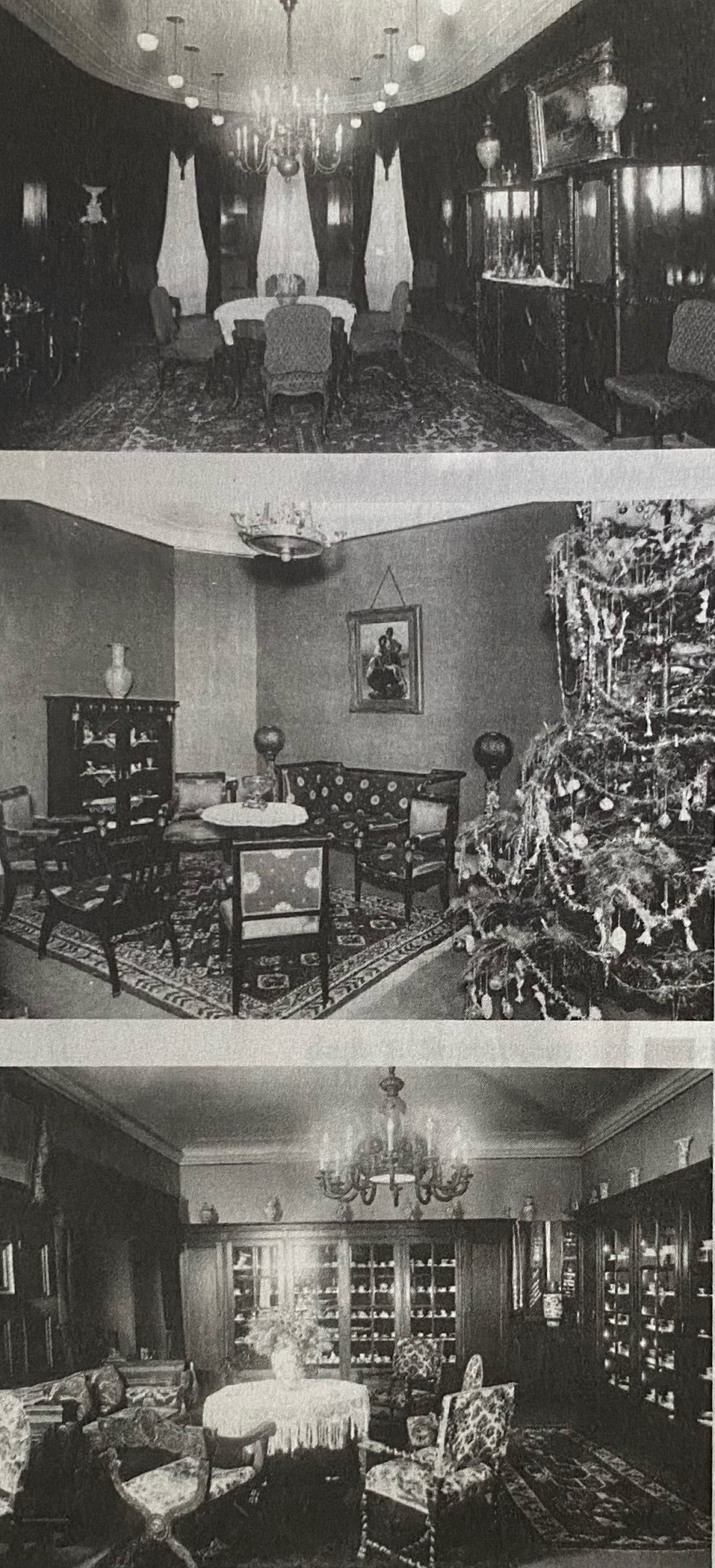

Yes, this is a German language book, but even if you do not speak German (well) you’ll want to have this publication for the wealth of images reprinted. You get to see all the original stars, scenes from all original productions, and from almost all films Ábrahám wrote music for. Many of these pictures will be unfamiliar even to diehard operetta fans. There are also pictures of Ábrahám’s famous villa in Berlin (you see the dining room, his coffee cup collection, the marble staircase, the outside façade, and then a picture of what the ruins looked like in 1952).

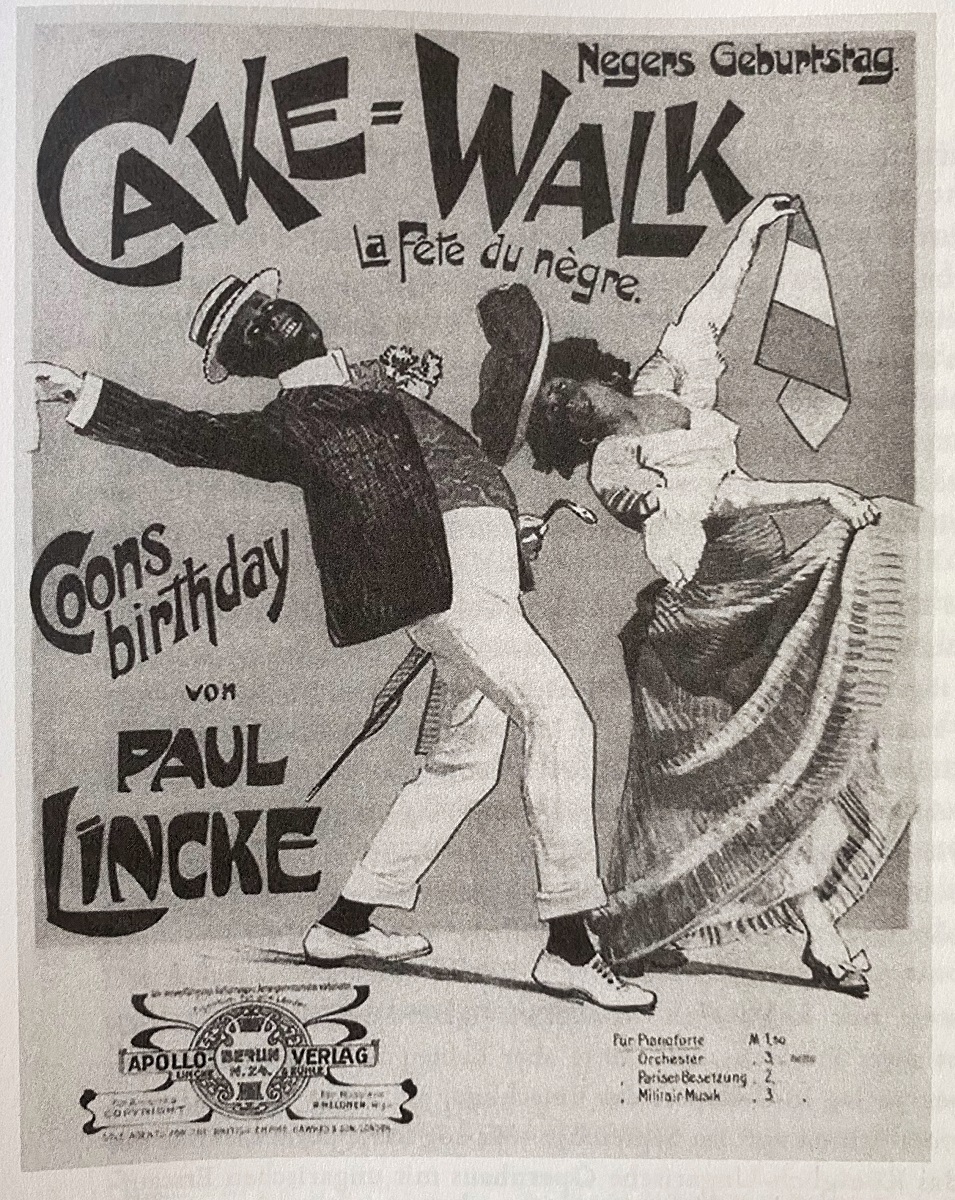

Sheet music cover for Paul Lincke’s cake-walk “Coon’s Birthday”. (Photo: From Karin Meesmann’s “Pál Ábrahám” / Hollitzer)

Karin Meesmann is keen to contextualize Ábrahám. So, very often, there are richly illustrated “excursions” to topics such as “The Cakewalk”, with sheet music covers of Paul Lincke’s “Negers Geburtstag” (“Coon’s Birthday”) from La Fete du nègre (published by Apollo Verlag in Berlin). Or there’s the song “Die lustigen Neger” by Harry S. Webster, a cake walks from 1902.

It’s not Meesmann’s aim to reproduce racist stereotypes, but to show how this new sort of music came to Germany and Hungary, and how Ábrahám came into contact with it. She links these Afro-American styles with the Hungarian “Verbunkos” and traces the unique sound world of Ábrahám to various other sources.

The 4 Black Diamonds in 1906 as they appeared at the Budapest Orfeum. (Photo: From Karin Meesmann’s “Pál Ábrahám” / Hollitzer)

Maneuvering His Way to the Top

In the biographical section, you get a lot of detailed information about his early life – beyond the many legends Ábrahám himself later put into circulation. The same is true when Meesmann analyzes how Ábrahám managed to enter the lucrative – but hermetically sealed off – operetta business of the late 1920s; she presents contracts that show how publishers specifically positioned Ábrahám as a competition to established composers such as Lehár and Kálmán, and brought him together with Lehár’s and Kálmán’s librettists to re-work shows that had premiered in Budapest, making them huge hits in Germany.

Ábrahám’s villa in Berlin, various rooms. (Photo: From Karin Meesmann’s “Pál Ábrahám” / Hollitzer)

The time after 1933 gets a close look at as well, with all works written after the blockbuster years in Berlin presented in an in depth way. We learn that Ábrahám continued to be very productive, in Vienna and Budapest, but these shows (and films) never reached the wider attention of the German market which was blocked because of the Nazis, claiming Ábrahám’s music was “degenerate”. There’s also a historic survey of the general political changes in Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

Ábrahám’s complicated escape to Cuba and New York is chronicled, his mental breakdown (caused by Syphilis), and his tragic later years, when he was brought back to an institution in Hamburg where he eventually died.

Abraham being escorted off the airplane on this return to Germany, after WW2. He was taken directly to a hospital to be treated for syphilis.

Original Letters, Reviews, and Documents

The narrative is enriched with many quotes from original reviews, from letters, and other historic documents. You might not always agree with Miss Meesmann’s interpretation of the shows in question, but she always explains her views well and invites the reader to argue back. So this book is, above all else, an invitation to discuss Ábrahám and jazz operetta in a fresh new way. To have achieved that is almost a miracle, and rather unique in the world of German language operetta research which is usually about who’s right and who isn’t.

This book is published by the Austrian publishing house Hollitzer. It widens the circle of Ábrahám biographies substantially, and has much more to say than Klaus Waller with his Paul Ábrahám: Der tragische König der Operette (2014) and Paul Ábrahám: Der tragische König der Jazz-OPerette (2021), not to mention various essays like Daniel Hirschel’s “Paul Ábrahám” in Operette unterm Hakenkreuz (which is, sadly, a special source of irritation for the author of this article). They are all listed in the bibliography of Meesmann’s book.

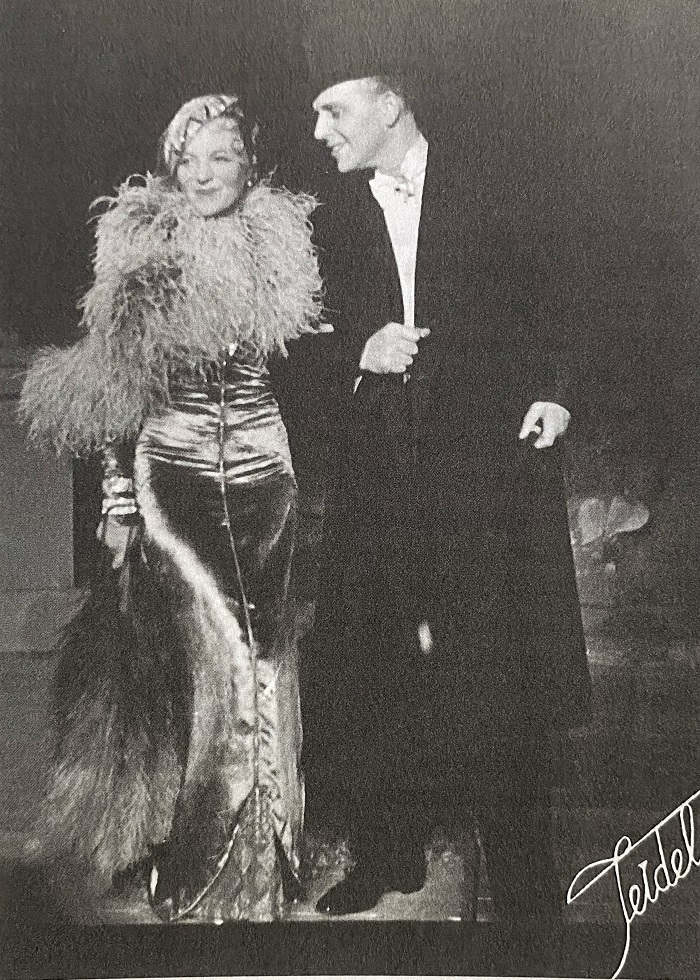

Gitta Alpár and Arthur Schröder as Madeleine and Aristide de Faublas in “Ball im Savoy”. (Photo: From Karin Meesmann’s “Pál Ábrahám” / Hollitzer)

However, all of these books and essays are in German. It’s really high time that something in English were published. One might as well start with Karin Meesmann’s book, since it’s the most in-depth study so far and the most wonderfully illustrated one.

Because the book is clearly structured, you can easily start reading any section that interests you (because a particular photo in the book draws your special attention, for example). So one doesn’t have to read from page 1 to page 500 to dive into the world of Ábrahám. I personally find this “openness” of the narrative a great bonus.

The London version of Abraham’s “Ball at the Savoy” with lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, showing Rosy Barsony on the cover.

And if you need the right soundtrack for this book, defintely choose the Duophon album with the restored original recordings; it doesn’t get any better than that!

The Duophon album of Paul Abraham, first released in 2001.

Karin Meesmann: “Pál Ábrahám: Zwischen Filmmusik und Jazzoperette” (hardcover, 21 x 29 cm), Hollitzer 2023, 552 pages, 68 Euros